A Streetcar Deemed Undesirable

December 2025

Download This Article (.pdf)

“How often does the train go by?”

“So often you won’t even notice it.”

—The Blues Brothers (1980)

In November 1890, Mary V. Macon purchased a double lot at the corner of Eleventh Avenue and Ogden Street in Denver. This prime parcel featured a 2½ story brick mansion with 14 rooms. Its Capitol Hill location was considered “one of the most desirable in the city.”1 The neighborhood’s Victorian style houses, including the Molly Brown House a few blocks away, were the home of Denver’s elite.

Over time, however, the neighborhood began to transition away from purely residential development. An early example was the construction of the Eleventh Avenue Hotel in 1903 at Eleventh Avenue and Broadway. The hotel was built in Italian Renaissance revival style but catered to a working-class clientele. Other businesses soon arrived in the neighborhood, beginning its transformation into a mixed-use neighborhood with both residential and commercial structures.

The Complaint

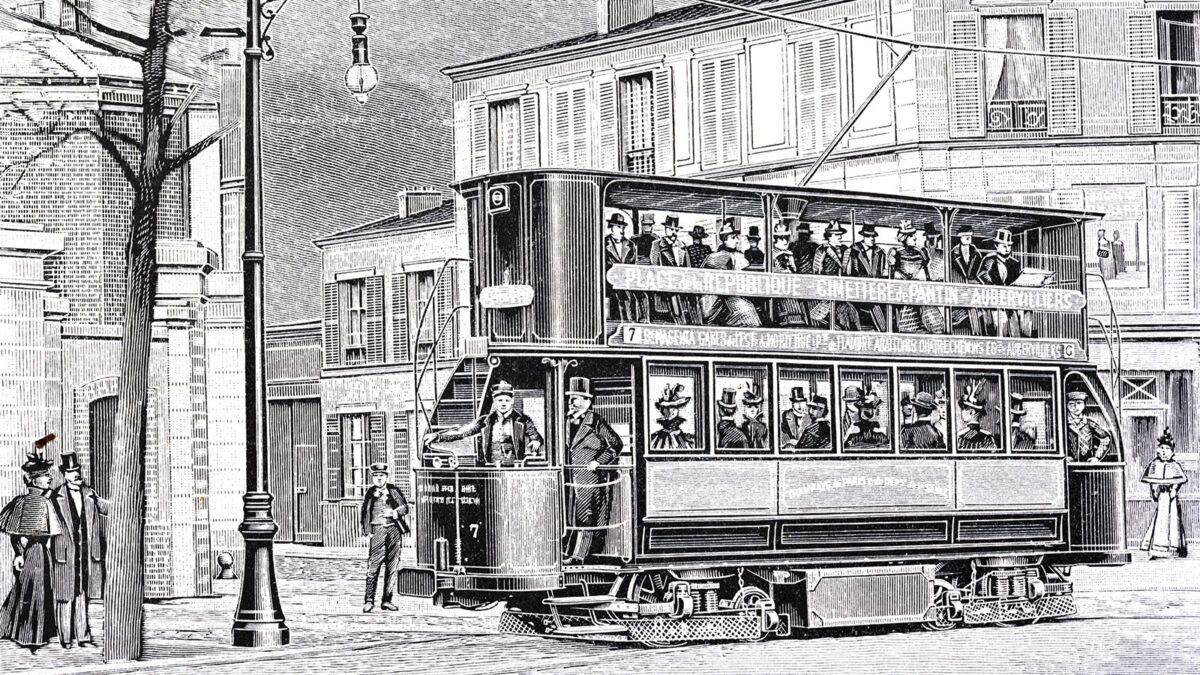

Ms. Macon’s complaint—the basis of her lawsuit—did not concern the change in the zoning or the character of her neighborhood. Rather, it involved a double-track streetcar line that was erected in 1897 by the Denver City Tramway Company.

The line ran from the business district along Eleventh Avenue up to Ogden Street. From there, the tracks ran east along Eleventh Avenue past Fillmore Street for another 15 blocks, connecting with the tramway’s Fairmont line. The company later added a second line that ran down Ogden Street through the intersection at Eleventh and Downing and that intersected with the tracks at Eleventh and Ogden.

Both sets of tracks ran right past Ms. Macon’s dream home at Eleventh and Ogden, flanking her double corner lot. The west rail of the tracks on Ogden Street ran as close as three feet from the curb in front of her home, passing within 35 feet of her residence. The tracks on Eleventh Avenue were 40 feet from her property line.

This created a logistical nightmare for the prominent Denverite, who frequently entertained guests at her home. (Ms. Macon was heavily involved in local politics, even serving as president of the Colorado Women’s Democratic Club,2 and was married to a prominent Colorado judge.) Before the tracks were built, visitors to Ms. Macon’s home could park their carriages or automobiles in front of her house and walk up the sidewalk to her front door. Now they had to park behind her house or down the street.

But a far worse problem was the noise. The streetcars ran by Ms. Macon’s house 40 times an hour. She complained that “the frequent passage of cars over the curves of the tracks makes a loud, grinding, shrill, and nerve-racking noise, and jars the building and creates almost a constant rumbling, disturbing sound, accompanied by the ringing and clanging of alarm bells and danger signals.”3 This near-constant noise made it impossible to carry on a conversation on her front veranda or even in the front part of the house. She could not “enjoy any form of social intercourse or entertainment during the day or evening, or enjoy undisturbed sleep at night, or occupy the house with any degree of comfort or quietude.”4 The streetcar’s disruptive operations, she averred, had also greatly reduced the rental and sale value of her property.

In December 1907, Ms. Macon sued the tramway company in Denver District Court. She alleged that by constructing its noisy and disruptive tracks near her house, the company had taken her property without just compensation, in violation of Article 2, section 15 of the Colorado Constitution.

Less than a year after filing the suit, Ms. Macon died. Her administrator, J. Henry Harrison, was substituted as plaintiff.5 The tramway company demurred to the complaint, arguing it failed to state a claim. The district court agreed and dismissed it.

The Appeal

The administrator appealed to the Colorado Supreme Court. The court began by explaining that although Ms. Macon had sued the tramway company, the company stood in the shoes of the city and could be liable if it had taken or damaged her private property. Physical damage to her property was not essential to her takings claim. But to recover damages she would have to show that the tramway company had wholly or partially destroyed some right, use, or interest she had in the property, diminishing its value.

To be actionable, any harm to her property would have to be unlawful. It would not be enough to show an incidental injury, without malice or negligence, “arising from a careful exercise of legal rights by defendant in a manner that does not invade the legal rights of plaintiff.”6 No matter how annoying or inconvenient the company’s actions, and no matter how much they reduced Ms. Macon’s property value, if the tramway company had been acting within its rights, she could not recover. Under the principle of “damnum absque injuria,” there is no recovery for a harm that does not violate the plaintiff’s legal rights.7

As the court explained it, the administrator had an uphill battle to overcome this principle, because a city “may use or authorize its streets to be used for all ordinary and necessary uses to which city streets are usually subjected.”8 In purchasing her lots, Ms. Macon should have been aware of the authority of the municipal government to use the nearby streets for public purposes. Installing streetcar lines did “not in any substantial respect destroy the street as a means of free passage common to all people, nor . . . impose thereon an additional servitude.”9 Ms. Macon and her guests could still access her property, even if the streetcars were frequently operated on the tracks, because the tracks themselves did not block her property. Nor did she have a right to free space between the tracks and her sidewalk where her guests could park. If vehicles needed to drop off people or goods to the house, of course, the streetcars would have to stop for them. But even those vehicles would have to share the street with the lawfully permitted streetcars.

As for the noise and disruption, Ms. Macon had failed to show that she was injured in a different way from the general public. “The annoyance, discomfort, and injury suffered by the plaintiff from the loud and disagreeable noises and vibrations produced by the cars passing over the tracks and around the curves, and the ringing of alarm bells at the place and times in question, are the same, except in degree, as are suffered by the public generally . . . .”10 The court cited case law stating that where a simple “inconvenience or discomfort of the occupants of the property” did not cause the property “to suffer any diminution in substance” or to be “rendered intrinsically less valuable” it was not “damaged within the meaning of the Constitution.”11 It therefore affirmed the district court’s dismissal.

The court’s last point seems a bit overstated. If Ms. Macon had specifically alleged that her property’s value had decreased, it seems like that would show, factually speaking, that it was diminished or made less valuable, regardless of the fact that the decrease in value resulted from inconvenience or discomfort to the property’s occupants. Whether that diminution or loss of value was actionable, of course, is a different question. But the loss of value itself did not cease to exist merely because it was not actionable.

In any event, two of the justices dissented. They noted that “[e]ach case is governed by its own peculiar facts,” and Ms. Macon’s complaint alleged facts sufficient to show “that the property in question has suffered such special damage as to call for compensation within the true intent and meaning of” the state constitutional provision.12 The dissenting justices would have overruled the district court’s demurrer.

Aftermath

Today, the corner of Eleventh Avenue and Ogden Street is entirely commercial. There is no sign of Ms. Macon’s dream house, or of the tramway tracks that made it a nightmare for her. The Eleventh Avenue Hotel on Broadway still exists and now serves as a hostel. Like many parts of Denver, the neighborhood has evolved with the times.

Notes

1. Harrison v. Den. City Tramway Co., 131 P. 409 (Colo. 1913).

2. The Woman Voter, p. 4 col. 3 (Aug. 2, 1894). See also https://coloradogenealogy.com/statewide/state_organizations_continue_suffrage_movement.htm.

3. Harrison, 131 P. at 410.

4. Id.

5. Harrison was Ms. Macon’s brother, and his role as administrator of her estate soon had him embroiled in litigation about contested deeds from Ms. Macon’s husband, Judge Thomas Macon, to her cousin Mary V. Harrison. The deeds were contested by Ms. Macon’s two other brothers, who claimed the Macon estate belonged to them. See “Fight a Girl for Macon Fortune,” Rocky Mountain News, p.1, col. 1 (July 30, 1908). The result of this dispute is unclear.

6. Harrison, 131 P. at 411.

7. Id.

8. Id.

9. Id. at 412.

10. Id. at 413.

11. Id.

12. Id. (Musser, C.J., dissenting).