Fake News

How to Spot It and How to Avoid It

May 2020

“Alie can travel half-way around the world before the truth gets its boots on.” This quote is said to be attributed to Mark Twain, although there’s no written or oral record of that fact. The quote and its potentially false attribution are a reminder that news travels fast (and can easily go viral) but is not always accurate. We are a society of information consumers, now more than ever. However, information overload can make it more difficult to make decisions and to differentiate the real from the fake. This is also true for the consumption of news.

In the past, when most people relied on print newspapers for their news, the expectation was that a reader would get the news from the day before. Now, the expectation is instant delivery of the news through online newspapers, news outlets, and social media sites. This goes hand-in-hand with the reader’s desire to reinforce his or her existing beliefs and disregard those that are contradictory.

Digital news consumption is high, especially among millennials, who rely heavily on social media sites like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter for their news.1 According to a Pew Research survey, 68% of adults report getting at least some of their news from social media.2 However, 57% assume that the news they receive will be “largely inaccurate.”3 Inaccurate news is not just an inconvenience but can also damage organizations that rely on it. In a law firm environment, reliance on bad data or false facts can lead to the loss of a client, a case, or a good reputation.

What is Fake News?

Fake news is essentially the dissemination of news stories that are not true, either because they are fabricated or because they are not verifiably accurate.4 Upon closer examination, fake news is not just false stories, but belongs to a larger universe of misinformation and disinformation. Misinformation is usually created by accident, with no intent to deceive. Conversely, disinformation is created to intentionally deceive, mislead, or force allegiance to a particular agenda or cause. Both misinformation and disinformation obscure the truth and can be easily shared and spread thanks to social media networks.5

According to Claire Wardle of FirstDraftNews.com, there are seven types of misinformation and disinformation: fabricated content, imposter content, misleading content, manipulated content, false context, false connection, and satire or parody.6 Fabricated content is totally false and intended to do harm through deception. Imposter content makes readers believe that it is from a verifiable or credible source, but it is not. Imposter content is often in video form because it’s easy to splice together snippets of truthful videos to create something false. Misleading and manipulated content take credible content and change it to deliberately deceive and mislead. Once upon a time, it might have been known as false advertising. False context forces readers to take credible information out of context so that the details become unclear. False connection is what drives “clickbait” on websites because it plays on readers’ curiosity. Finally, content that is satirical or a parody is meant to be humorous but can easily be misinterpreted as serious. There is often no good way to verify the content of a satirical news site, making it difficult to tell if a story is real or fake.7

How Did We Get Here?

The creation and existence of fake news is certainly a problem, but that problem grows exponentially when readers share news or information that is false or misleading. What motivates people to share news or information, both fake and real? According to Jeff Sonderman, digital media fellow at the Poynter Institute, there are five primary motivations for sharing content:

- altruism—bringing valuable and entertaining content to others;

- self-definition—sharing to define ourselves to others;

- empathy—sharing to strengthen our relationships;

- connectedness—sharing to get credit for being a good sharer; and

- evangelism—sharing to spread information about something we believe in.8

In a society of sharers, how do we keep from being part of the proliferation of fake news? We need to slow down the intake of information and give concentrated thought to whether the information we are receiving is true, false, or somewhere in between. According to The Verge, a multimedia project started in 2011 that examines how technology will change life for the masses, there are four steps we can take to fight false online information.9 The first step is to figure out when to be worried, meaning it’s important to be able to spot red flags. If something seems too amazing or too horrifying to be true, it just might be false. Be on the lookout for news that overtly appeals to strong emotions, asks you to spend money, or plays on a sense of partisanship or bias.

The second step is to make sure the URL or link is legitimate. Part of looking more deeply into the source of a news story is to determine where it comes from. Details easily get lost in a repost or multiple reposts, so checking the origin of the information is paramount. Try to find the original date of the story before it was reposted (or a timestamp) and see whether the original story cites to reputable sources. If it’s unclear where the story originated, try using multiple search engines to find additional coverage of the news story or any sort of identifying source information. Sometimes it’s difficult to tell whether online information is fake or deceptive. Instead of being blatantly or ridiculously false, online information can leave out simple details or make small details overly important. Sometimes online news can feature a mix of fake and real information, leading to further confusion.

Step three is to find the context of the information by determining who is providing the information, how the information is presented by different news outlets, and whether the story is actually satire.

The last step is to determine what the news story or information really means. You certainly can’t or even shouldn’t believe everything you read, but assuming that everything online is fake is also a mistake. Strive to determine whether important facts have been left out of a story or if the story is missing that larger picture. Slow down and think about the consequences of sharing a story that is false or misleading and why a particular story should or should not be shared.

Anybody can be fooled by online content, even reputable news sources and highly skilled researchers. Online news and information disseminated through social media is not always black and white. The existence of false, misleading, or deceptive information does not mean that nothing is true or that everything online is fake. However, it does mean that researchers need to think critically about what they find online, what they share and repost, and what news sources they rely on.

How Do You Spot Fake News?

Lawyers are trained to view defendants as innocent until proven guilty; however, if fake news were a defendant, it would likely be the other way around. A healthy dose of skepticism can be an asset when researching news sites. Law librarians are trained to evaluate information for authenticity and accuracy and often teach courses to law students and others on information literacy.10 Spotting and identifying fake news can be time consuming and confusing, but there are some basic guidelines researchers should keep in mind:

- Check the source of the information, either by clicking the “About Us” or “Contact” pages. If the site does not have these pages, that is a red flag.

- Do a quick biography check on the author or organization writing and/or posting the story.

- Do a quick Google search of the website and see what others have said about it.

- Look at the URL to see if it looks unusual or unexpected.

- Don’t be lured in by sensational headlines or outrageous claims, and make sure the author did not bury the lead just to get clicks.

- Is the story reported by other reputable news sites? Make sure to read multiple stories to check sources.

- Sloppy writing, poor grammar, and misspelled words are a red flag that a site or story is fake.

There are many resources that can help researchers evaluate online information and news sites to determine whether they are real or fake. Several of these resources are discussed below.

The CRAAP Test

The CRAPP test was developed by Sarah Blakeslee at California State University–Chico in 2004.11 The test is divided into five parts: currency, relevance, authority, accuracy, and purpose. When evaluating currency, a researcher must consider the timeliness of the information, which can be determined by looking at the publication date, whether the information has been recently updated, whether the information is current for the topic, and—for online sources—whether the links are functional or broken. A resource’s relevance hinges on how important the information is to the research. Researchers should consider who the intended audience is and whether the education level is appropriate for the intended audience. Authority is the source of the information and whether the author is qualified to write about the topic. Researchers should make sure that the author’s credentials or the organizations affiliations are readily available. Researchers should evaluate the author’s credentials and investigate what the URL (for an online source) or the publishing house (for a print source) reveals about the source.

Accuracy underlies the other components and is the most important because it involves analysis of the “reliability, truthfulness, and correctness of the content.”12 The language and tone should be free of bias and emotion and there should be no spelling, grammar, or other errors. Lastly, the purpose is why the information exists. Researchers should make sure that the purpose of the information is clear (i.e., it is meant to inform, teach, entertain, persuade, etc.). It is also necessary to determine whether the information is factual and objective or if it is opinion, propaganda, biased, or trying to further an agenda.

The CRAAP test is meant to help researchers determine if sources are accurate and reliable. It is neither foolproof nor static, as different criteria may have more or less importance as the situation warrants.

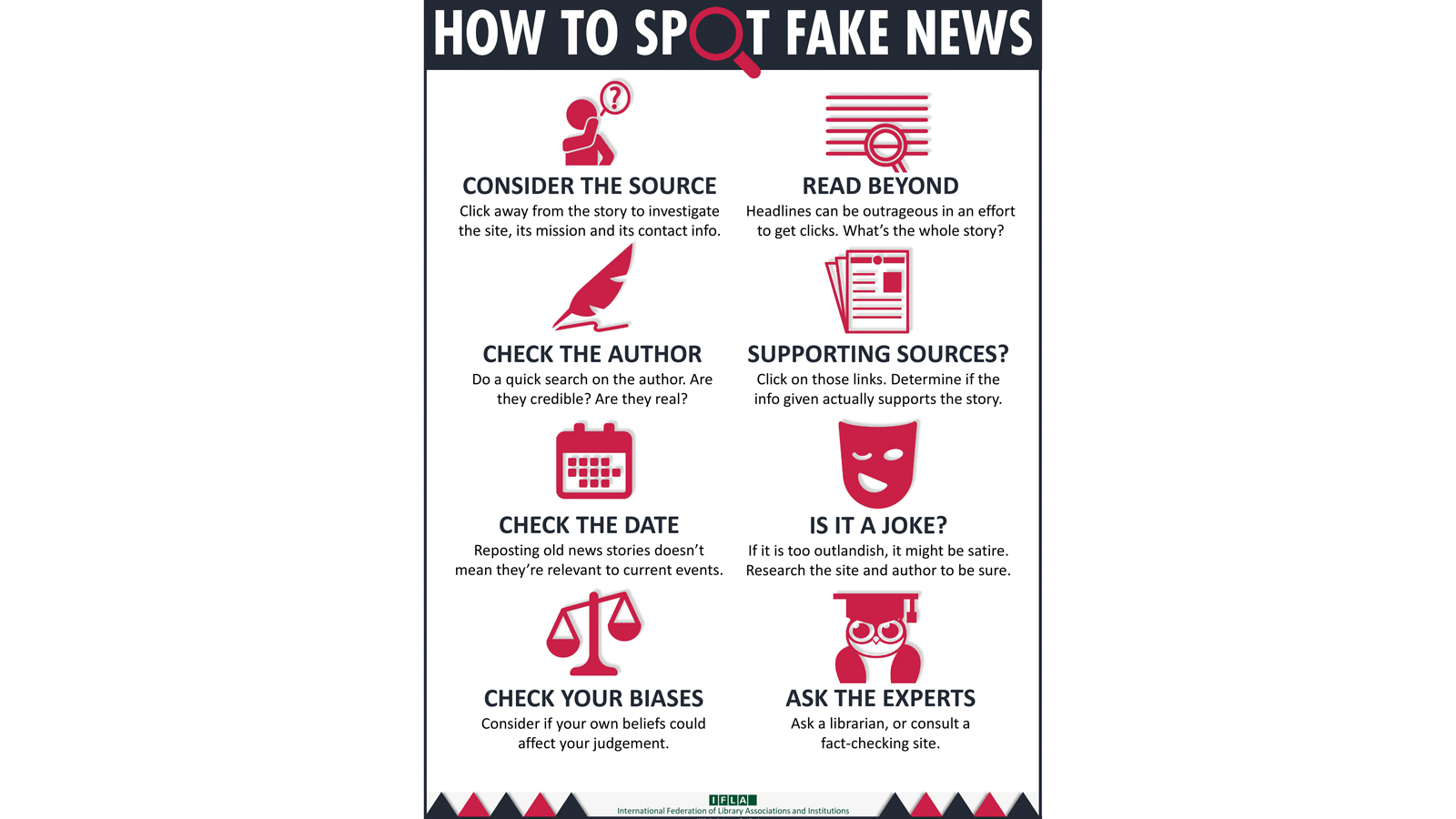

The IFLA Guide to Spotting Fake News

The International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) is the leading international body representing the interests of library and information services and their users. It is the global voice of the library and information profession.13 In response to the growing existence of “fake news” in everyday parlance, IFLA created the above infographic to serve as a guide and checklist for researchers in determining the accuracy and veracity of news and other information.14 The infographic has since been translated into 36 different languages.

FactCheck.org

FactCheck.org15 is a project of the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Policy Center, a nonprofit organization that acts as a consumer advocate for voters. Its stated mission is “reduc(ing) the level of deception and confusion in U.S. politics.”16 By monitoring the content of television advertisements, debates, speeches, interviews, and news releases, FactCheck.org helps to increase public awareness of what is fake information and what is truthful.

The website allows researchers to ask questions and to search an archive of previously asked questions, on a variety of topics. FactCheck.org is one of several organizations that works with Facebook to debunk misleading information that has been posted to social media sites. There are also sections that focus on false or misleading scientific claims (SciCheck), viral claims, and on-air statements. Researchers can also perform Google-like natural language searches to find information about topics in the current news cycle, such as the coronavirus or the 2020 presidential race.

Snopes.com

Snopes.com bills itself as “the internet’s go-to source for discerning what is true and what is total nonsense.”17 The site’s team of researchers has been fact checking for over 20 years, and the site boasts an impressive archive based on topics, as well as ratings (e.g., true, mostly true, a mixture, mostly false, false, unproven, misattributed, outdated, or scam). Snopes tends to focus its fact checking and fake news debunking on hot topics, the top 50 rumors circulating on the internet, and current news stories. Snopes.com researchers list the materials they use to check facts so users can further verify information.

It is also one of the only fact-checking sites that includes satire and humor, and has been since it launched in 1994. Urban legends are often humorous stories that are told as the truth and grow from there. The proliferation of online news and social media sites means that satirical information is presented in snippets or out of context and is difficult to identify; it’s the 21st century version of playing “telephone.”

What Does the Future Hold?

Enhanced video editing and AI technologies that swap people’s faces, synthesize and manipulate images, or recreate voices will further blur the lines between what is real and what is fake (or constructed). Fake videos, or “deepfakes” as they are referred to by lawmakers and intelligence officials, are “fabricated media produced using artificial intelligence . . . in which individuals appear to speak words and perform actions, which are not based on reality.”18 Spotting these deepfakes in the future will become as essential as spotting fake news is now. While the platform is different, researchers can still use the techniques outlined in this article to evaluate video for accuracy and veracity: consider the source, the creator, and the context.

Conclusion

Many factors influence how we process the material we are exposed to, and the modern digital information landscape has significantly impacted those factors. A critical eye will always be important in the fight against fake news and deceptive information.

Related Topics

Notes

1. Shearer and Matsa, “News Use Across Social Media Platforms 2018,” Pew Research Center (Sept. 10, 2018), https://www.journalism.org/2018/09/10/news-use-across-social-media-platforms.

2. Id.

3. Id.

4. University of Michigan Library, “Fake News,” Lies and Propaganda: How to Sort Fact from Fiction, https://guides.lib.umich.edu/fakenews.

5. Affelt, All That’s Not Fit to Print: Fake News and the Call to Action for Librarians and Information Professionals 13 (Emerald Pub. 2019).

6. Wardle, “Fake News, It’s Complicated,” First Draft (Feb. 16, 2017), https://firstdraftnews.org/latest/fake-news-complicated.

7. Id.

8. Sonderman, “5 reasons people share news & how you can get them to share yours,” Poynter Institute (July 19, 2011), https://www.poynter.org/reporting-editing/2011/5-reasons-people-share-news-how-you-can-get-them-to-share-yours.

9. Robertson, “How to fight lies, tricks, and chaos online,” The Verge (Dec. 3, 2019), https://www.theverge.com/2019/12/3/20980741/fake-news-facebook-twitter-misinformation-lies-fact-check-how-to-internet-guide..

10. “As ALA defines it, information literacy is a set of abilities requiring individuals to ‘recognize when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information.’ To be information literate, then, one needs skills not only in research but in critical thinking.” https://literacy.ala.org/information-literacy.

11. Meriam Library, California State Library–Chico, The CRAPP Test, https://libguides.csuchico.edu/c.php?g=414315&p=2822716.

12. Affelt, supra note 5 at 61.

13. https://www.ifla.org/about.

14. https://blogs.ifla.org/lpa/files/2017/01/How-to-Spot-Fake-News.pdf.

15. https://www.factcheck.org.

16. https://www.factcheck.org/about/our-mission.

17. https://www.snopes.com.

18. Affelt, supra note 5 at 107.

The creation and existence of fake news is certainly a problem, but that problem grows exponentially when readers share news or information that is false or misleading.