Finding Open Access Legal Scholarship

September 2023

Download This Article (.pdf)

Legal scholarship has undergone a major shift over the past 14 years. Once primarily behind subscription paywalls, most law reviews are now openly accessible online.1 This article aims to help attorneys navigate this shift by offering practical tips for locating free and accessible law review articles. It begins with an overview of the open access movement in law and its advantages for the legal profession, particularly in terms of legal research.

Overview

Law review articles remain a vital component of the legal research toolkit. Most attorneys are trained to consult law review articles as valuable secondary sources. While many in the profession perceive a divide between the practice of law and legal scholarship,2 the opposite is also true. As an academic law librarian, I commonly receive requests from law school alumni seeking access to scholarly articles.

Until 14 years ago, law review articles were available either in print, at a law library, or through Lexis, Westlaw, or HeinOnline. Then in 2009, law library directors from the nation’s top law schools met and wrote the Durham Statement, where they agreed to work toward ending the reliance on print subscriptions and making legal scholarship immediately available upon publication in an open and accessible digital format.3 Since then, academic law libraries have steadily canceled their print subscriptions and shifted those resources toward building institutional repositories. Institutional repositories store scholarly works and make them freely accessible online.4

The open access movement in law has steadily progressed. By 2018, nearly half of all law schools accredited by the American Bar Association (ABA) had institutional repositories.5 According to a 2019 study, 88% of law journals had a recent volume available for free online.6 More than half had their entire runs online. Though recently published, the 2019 study under-represents the amount of free legal scholarship available. Law schools are still building their institutional repositories. In 2019, only 3% of the Denver Law Review was available online. Four years later, the University of Denver Sturm College of Law’s institutional repository now contains complete runs of five Denver law journals, including 100 years of the Denver Law Review.7 By investing staff time and money into these projects, law schools demonstrate a painstaking commitment to sharing knowledge across wider reaches of the legal profession.

Increased access to legal scholarship could not be coming at a better time. Legal research is being discussed as a topic for the NextGen bar exam, with at least one author proposing a sample question that explicitly asks bar exam takers to find a law review article relevant to the proposed fact pattern.8 The conventional wisdom for using law review articles for legal research is to comprehend a narrow issue in great detail and find substantial citations. Most law review articles have a uniform structure well-suited for understanding a complex topic. Written for the general and law-educated audience, the typical article has four parts: introduction, background, analysis, and conclusion. In addition to critically evaluating existing approaches to a legal problem, the background and analysis sections offer comprehensive references to primary and secondary authorities.

Searching for Open Access Law Review Articles by Keyword

With the growing availability of open access law review articles, it’s important for attorneys to understand how to effectively search the various digital repositories. A successful search often begins in one of two ways: searching by keyword or searching by citation.

Searching by keyword is generally the more difficult approach. A successful search may require visiting one or more of these sites: (1) Google Scholar, (2) Law Review Commons, and (3) the Social Science Research Network (SSRN).

Google Scholar

Law schools host their institutional repositories on many different platforms.9 Two major platforms are the commercial provider Digital Commons and the open-source platform DSpace. To search within this decentralized system, Google Scholar is a helpful place to start. Google Scholar is a web-based academic search engine. Instead of searching all the indexed web, it limits itself to the content of institutional repositories, professional societies, and academic publishers.10

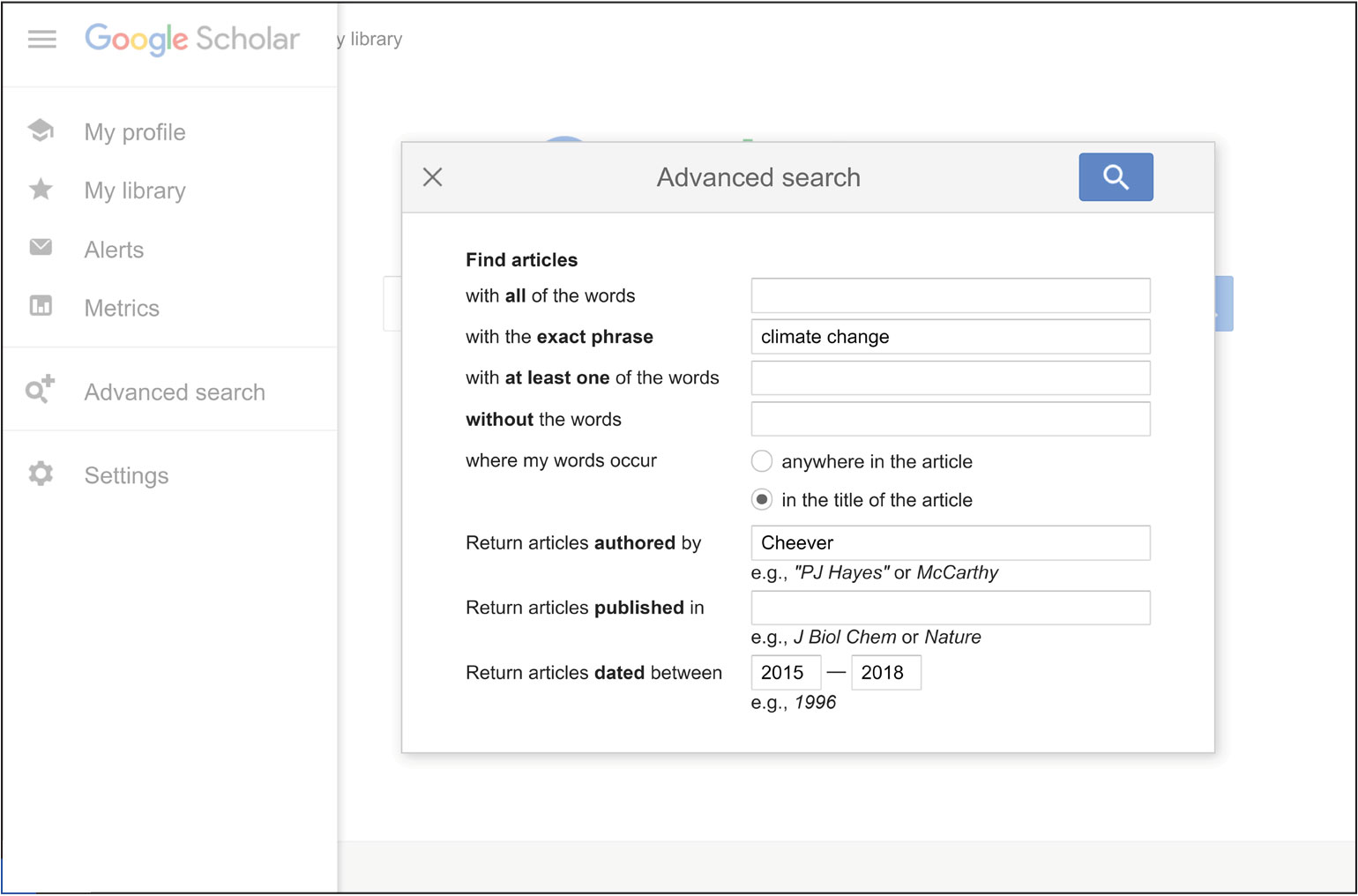

Google Scholar has a main search bar and an advanced search box. Located under the menu icon, the advanced search helps to refine a keyword search and improve results. For example, the user can direct the system to find articles with an exact phrase. The advanced search box also includes fields for author, publication, and date.

Users can also add the usual Boolean commands like AND, OR, and NOT directly into the search bar. If there are no commands, Google Scholar follows a familiar set of rules. AND is automatically implied by a space. By default, the system searches all fields, including full text. Capitalization and common words are ignored.

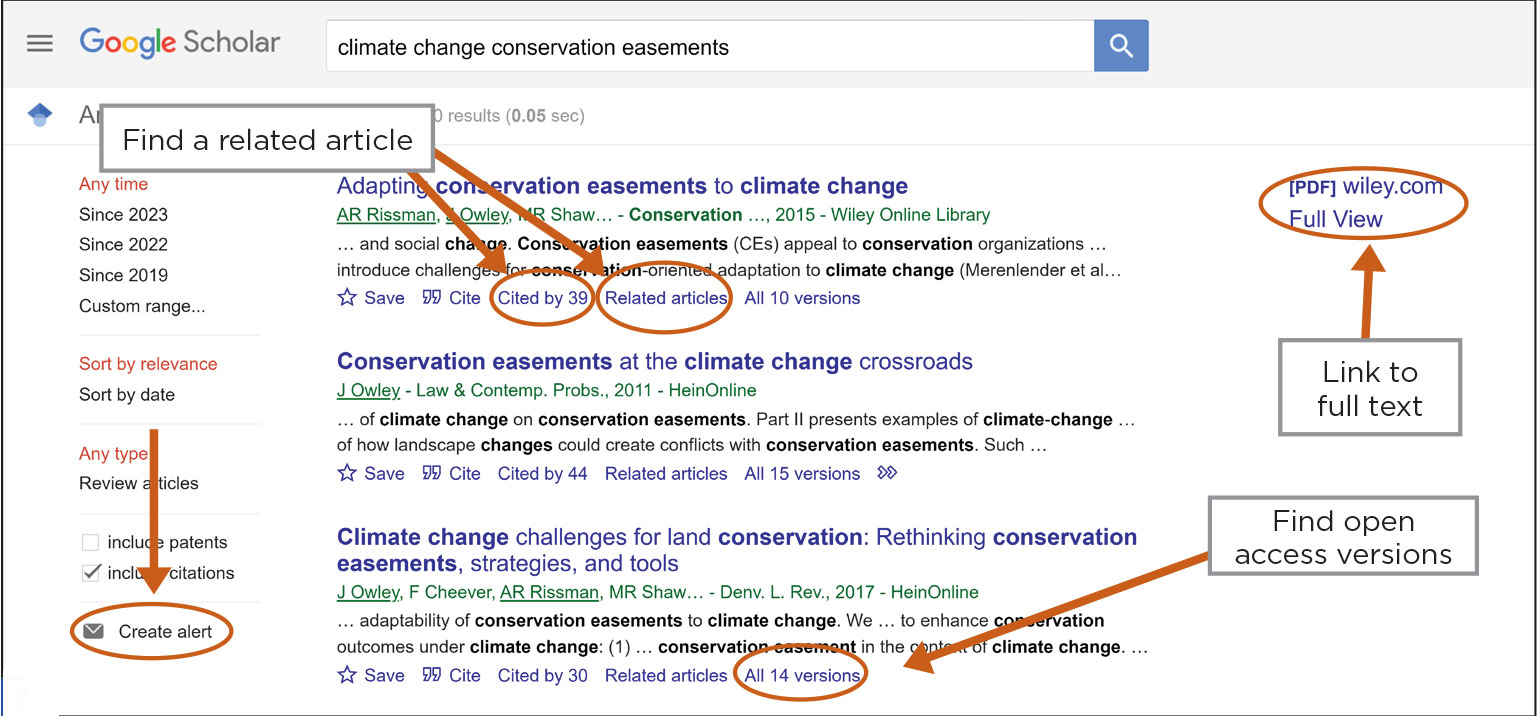

A successful Google Scholar search also depends on the user’s familiarity with the filters and features of the results screen. The filters include date and sort options. To find similar work, click on “Related articles” or “Cited by.” For search suggestions, scroll to the bottom of the screen. In the right-hand column, you will find the link to the full-text article. The Google search algorithm is trained to take users to accessible versions. However, if this link takes you to a paywall, select all versions instead (“All 13 versions”). Located directly beneath the result, this link may lead to an open-access version of the same article. You can also set up Google alerts. By entering any email of your choice, you will receive notifications when newly published papers match your search criteria.

In image 2, the third result is an article titled “Climate Change Challenges for Land Conservation: Rethinking Conservation Easements, Strategies, and Tools,” published in the Denver Law Review. The result shows access to full text only for subscribers to HeinOnline. Choose the “All 14 versions” link to access open versions from the University of Denver, Indiana University, and the University of Miami.

The first result is from a scientific journal. Google Scholar is not discipline-specific and will probably yield an overwhelming set of results. Not everything will be scholarly; results may include PowerPoint presentations and newsletters. Although its algorithm may rank law review articles higher, even top results will not be exclusive to legal scholarship.

Law Review Commons

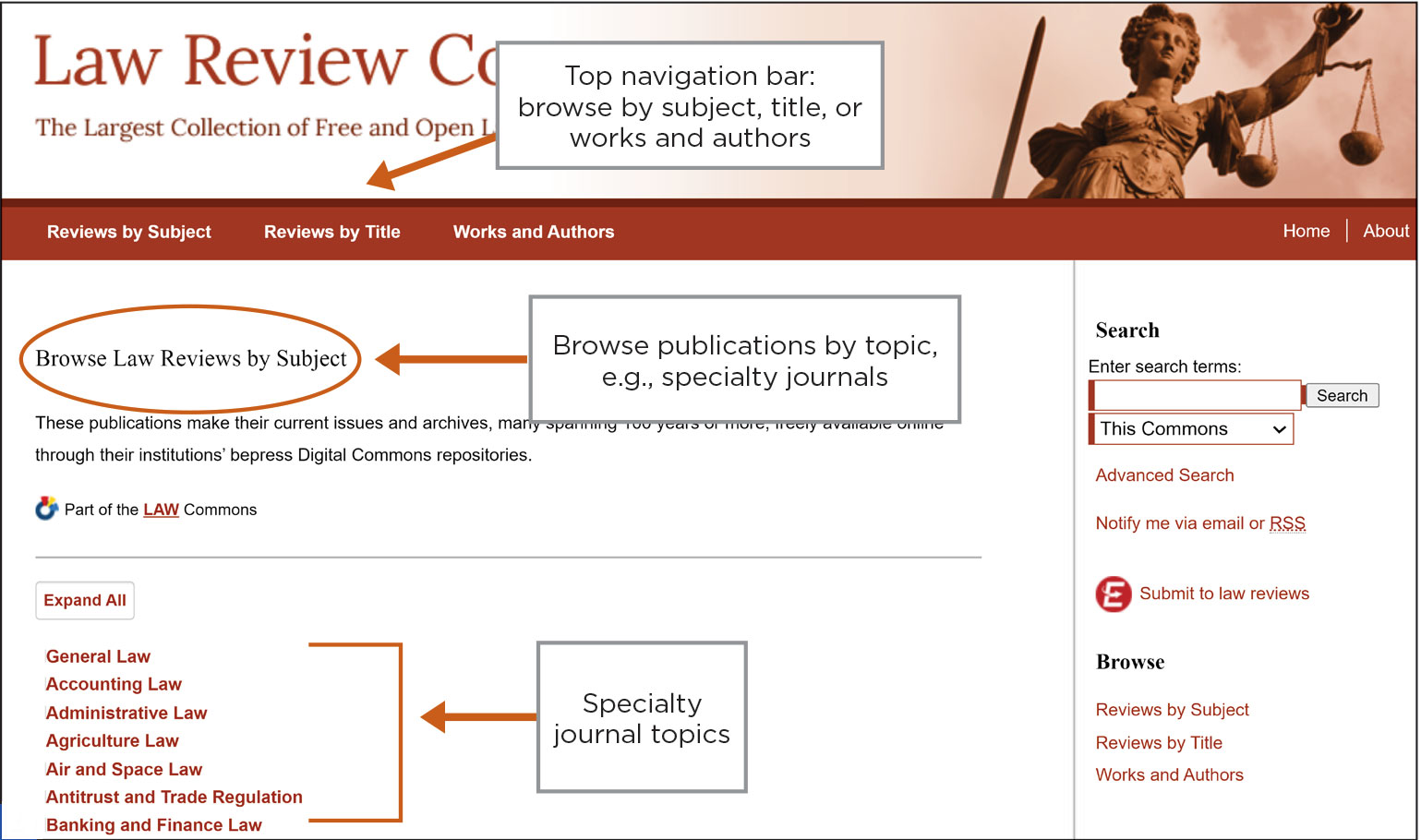

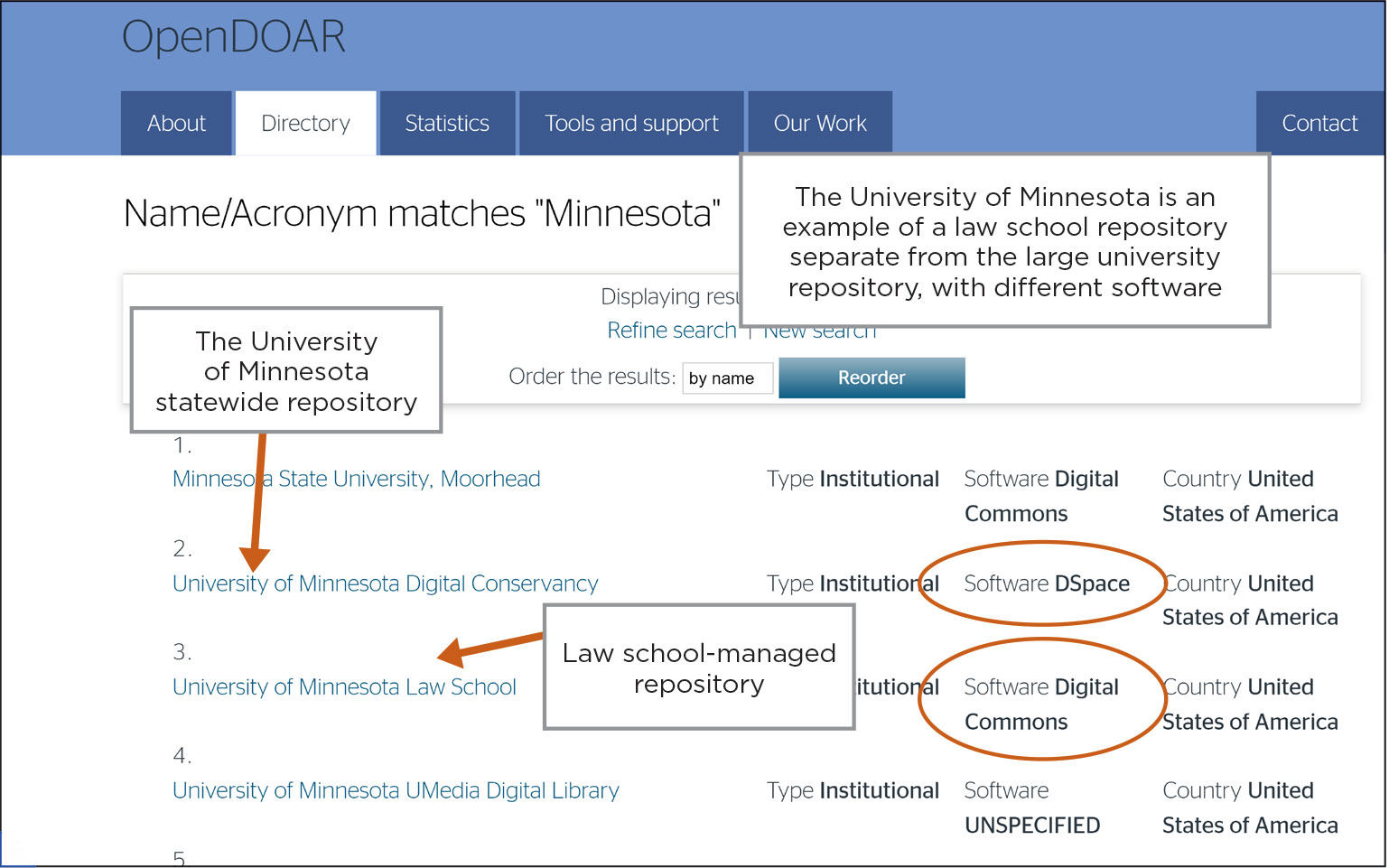

To search only legal scholarship, attorneys can use the website Law Review Commons.11 As the portal for the Digital Commons platform, Law Review Commons allows researchers to search for a large majority of ABA-approved law schools’ repositories, including the University of Denver and the University of Colorado.12 However, it is not comprehensive. It does not contain repositories hosted on other platforms, such as the open-source DSpace. To learn the software used by a particular institution, use the Directory of Open Access Repositories (OpenDOAR).13

Law Review Commons allows you to browse reviews by subject or titles, or for authors and works. The browse by subject or title function is only at the publication level, not at the article level.

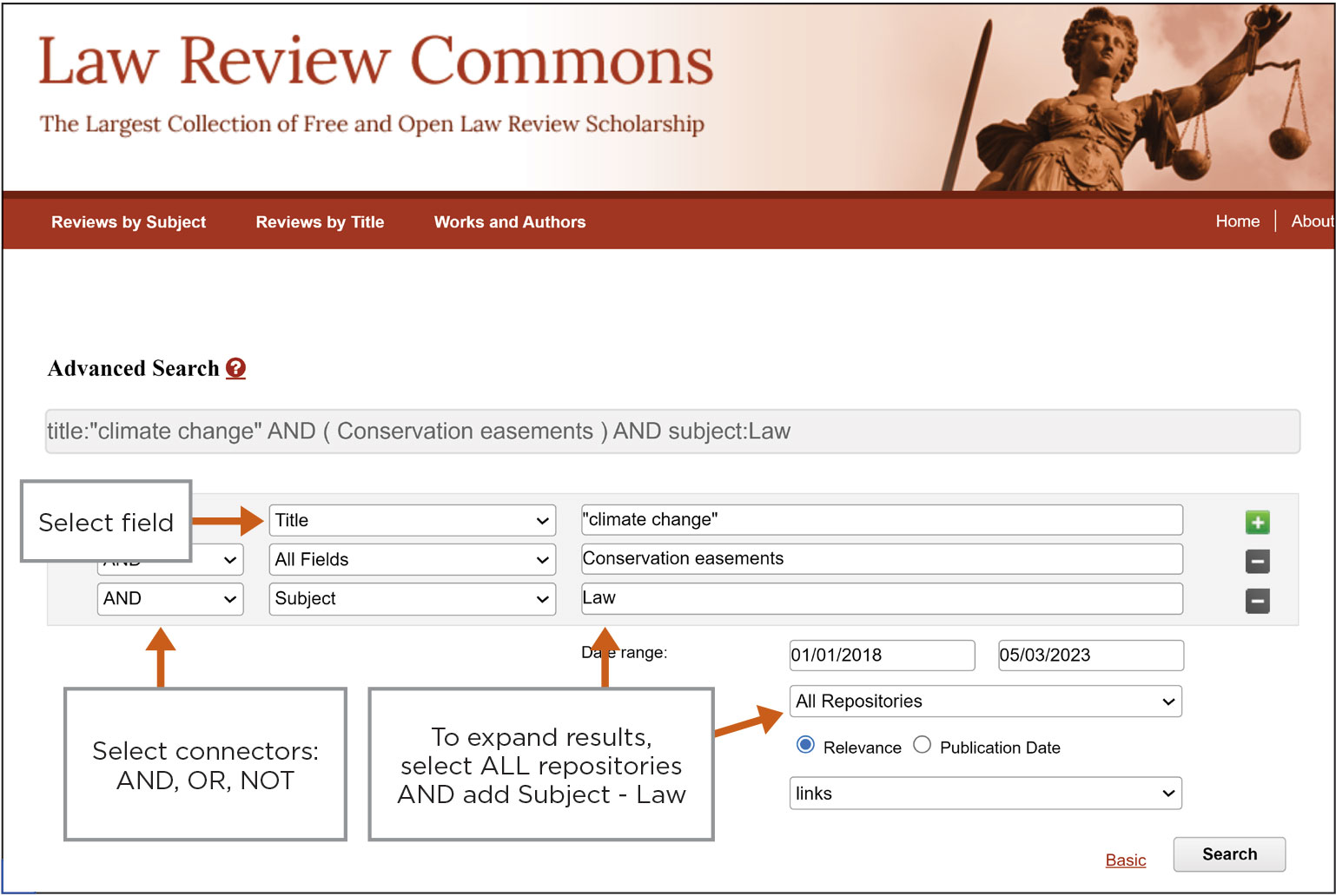

To search for articles, the Law Review Commons has an advanced search function that helps you build a search query using keywords. You can select Boolean connectors and specific fields using the drop-down menus. You can also filter by date. The advanced search will default to searching the Law Review Commons. If your initial search does not return any relevant results, expand your search to “All Repositories” and add a search term for “law” in the subject field.

A related website is Law Commons.14 Law Commons is also limited to Digital Commons repositories, but it contains all of their contents, not just law reviews. Additional content types might include lectures, memorials, and other historical material. The Law Commons website showcases popular authors, articles, and institutions with available download statistics. It does not have the same advanced search as the Law Review Commons.

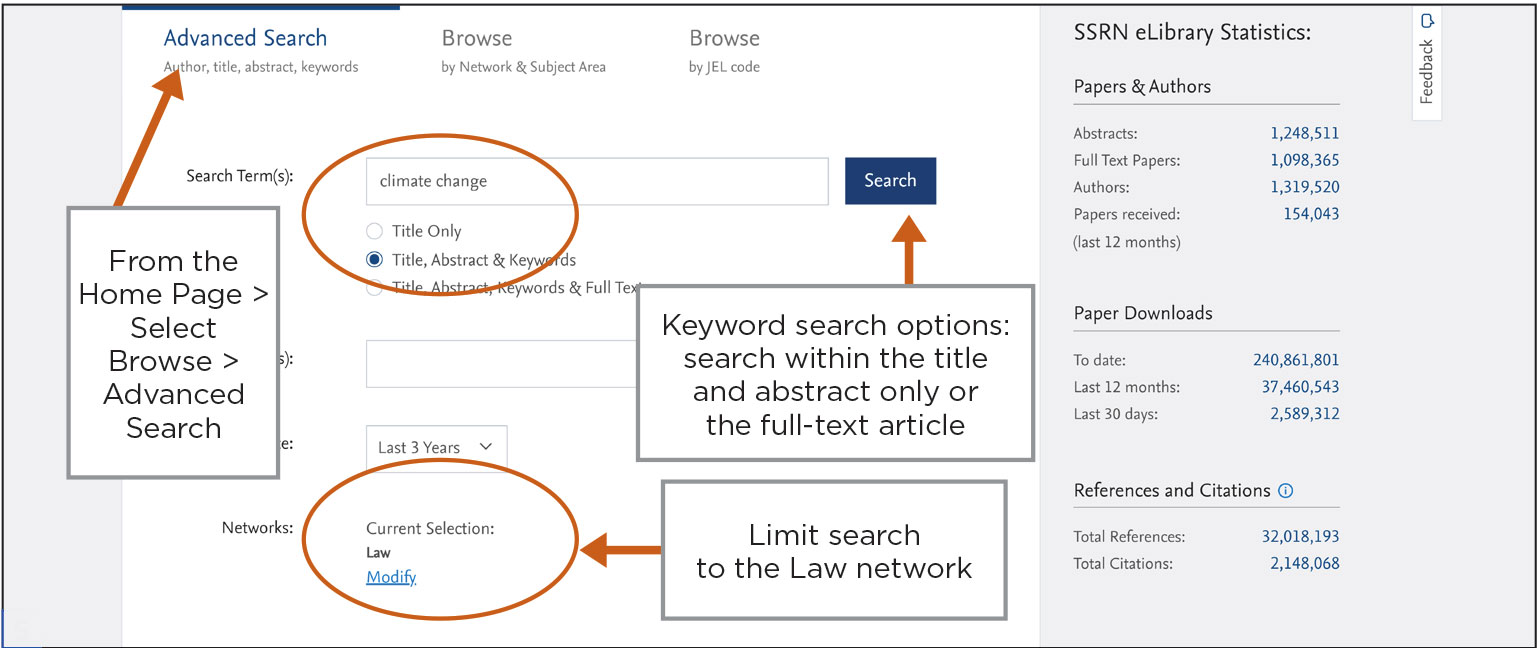

Social Science Research Network

SSRN is another type of digital repository. While institutional repositories focus on the intellectual output of an institution, SSRN is designed to promote individual scholars.15 SSRN is a conglomeration of over 70 networks, including the Legal Scholarship Network (LSN). Legal scholars submit pre-published and published works to SSRN, which then sorts them into subject-specific eJournals.16 Attorneys can search SSRN for individual articles, authors, and eJournals. Attorneys can also subscribe to eJournals and be notified when a new issue comes out. One advantage of SSRN is the abstract view. Authors are required to submit an abstract along with their full-text article. Although not a typical feature of a law review article, the abstract allows the user to quickly determine if the article meets their research needs.

Searching by Citation

Searching by citation is generally more straightforward. If you have a citation, you can look to see whether the law school has an institutional repository, or if not, whether the article is available on the law review’s website. To find a smaller school’s institutional repository, a simple Google search may be enough. For a large statewide system such as the University of Minnesota, it is easier to start with the OpenDOAR directory. The directory will also help you determine if the law school independently owns its repository or if it is university managed.

Each Digital Commons repository offers a basic search tool and an advanced search, like the one for the Law Review Commons. University-managed repositories may allow you to browse by schools and collections. For example, the University of Denver Digital Commons allows browsing by collections, disciplines, and authors.

If you have a citation, there is no law school repository, and the article is not appearing on a Google Scholar search, don’t assume it isn’t available through open access. Articles may be available on the law review’s website, which are often separate from an institutional repository. Law review websites are less likely to be indexed by Google Scholar, so articles on these websites may not appear in search results.

Unsuccessful Searches

Aside from the indexing of law review websites, there are other reasons why your search may be unsuccessful. Recent articles may be subject to publisher embargoes. Embargoes prohibit the online publication of an article for a specific period, usually one to two years. Their purpose is to maintain print subscriptions. Even commercial databases such as HeinOnline are subject to publisher embargoes. You may be able to find a pre-published version on SSRN.

Successful search results also depend on the quality of the metadata.17 Search engines like Google Scholar use software to identify the bibliographic data of law review articles. The data types include author(s), title, publication, and date.18 Incorrect data or missing data will lead to poor indexing and may lead to an article’s lower ranking or not being included at all.

With all the advancements in the open access movement, there is no search tool comparable to what is available through a discipline-specific subscription database. If you frequently search for law review articles, adding a low-cost subscription to a commercial database may save you time and money. The key advantage of having a law review database subscription is its powerful search function within a comprehensive database of legal scholarship. Currently, CBA members can add a HeinOnline subscription to their Fastcase account for $625 annually or $62.95 monthly.19 This allows access to up to 50 law review articles per month.

Conclusion

Searching for open access law review articles requires a patient and piecemeal approach. Attorneys can search on Google Scholar, Law Review Commons, and SSRN for freely available legal scholarship. If seeking a particular article, verify that the school has an institutional repository, how it is organized, and whether the article is available. If it is not in the repository, the article may be available on the law review’s website. Law schools have invested significant resources into building institutional repositories for sharing legal knowledge. A key next step for advancing the open access movement is to inform practitioners on how to find these secondary sources to meet their legal research needs.

Related Topics

Notes

1. For simplicity, I use the term “law review articles” to include works from both law reviews and law school specialty journals.

2. Beatty, “Open Access Without Open Access Values: The State of Free and Open Access to Law Reviews,” 115 L. Libr. J. 41, 43–44 (2023).

3. “Durham Statement on Open Access to Legal Scholarship” (Feb. 11, 2009), http://law.duke.edu/lib/durhamstatement.

4. Liebler and Cunningham, “Can Accessibility Liberate the ‘Lost Ark’ of Scholarly Work?: University Library Institutional Repositories Are ‘Places of Public Accommodation,’” 52 UIC J. Marshall L. Rev. 327, 329 (2019).

5. Schilt et al., “Rethinking Digital Repositories and the Future of Open Access,” 22 AALL Spectrum 28, 29 (2018).

6. Beatty, supra note 2 at 42.

7. University of Denver Sturm College of Law, Digital Commons @ DU, https://digitalcommons.du.edu/denver_law.

8. Meyer, “Adding Legal Research to the Bar Exam: What Would the Exercise Look Like?,” 53 Akron L. Rev. 107, 129 (2019).

9. Simms, “Trends in Use of Institutional Repositories for Faculty Scholarship in ABA-approved Law Schools,” 38 Legal Reference Servs. Q. 64, 65 (2019).

10. Google Scholar, http://www.scholar.google.com/intl/en/scholar/about.html.

11. Law Review Commons, http://lawreviewcommons.com.

12. Simms, supra note 9 at 72 (In 2019, 111 out of 136 law school institutional repositories were on the Digital Commons platform.).

13. OpenDOAR, https://opendoar.org.

14. Law Commons, http://network.bepress.com/law.

15. Jones, “Libraries Can Help: Institutional Repositories,” 30 T. M. Cooley L. Rev. 253, 256 (2013).

16. Wherry, “Tools for Improving Distribution, Discussion, and Downloads: An Informed Approach to Submitting Legal Scholarship to SSRN,” 100 U. Det. Mercy L. Rev. 223 (2022).

17. See Simms, supra note 9 at 68.

18. See “Inclusion Guidelines for Webmasters,” Google Scholar (May 15, 2023), https://scholar.google.com/intl/en/scholar/inclusion.html#indexing.

19. Your Legal Research Member Benefit, Colorado Bar Association, http://cobar.org/Fastcase (members must sign in to their CBA account and proceed to their account profile in the upper-right-hand corner; from the drop-down menu, select the “Account Management” hyperlink and follow to the “Manage Subscriptions” hyperlink).