Legal Community Celebrates New Irving P. Andrews Inn of Court

January/February 2025

Download This Article (.pdf)

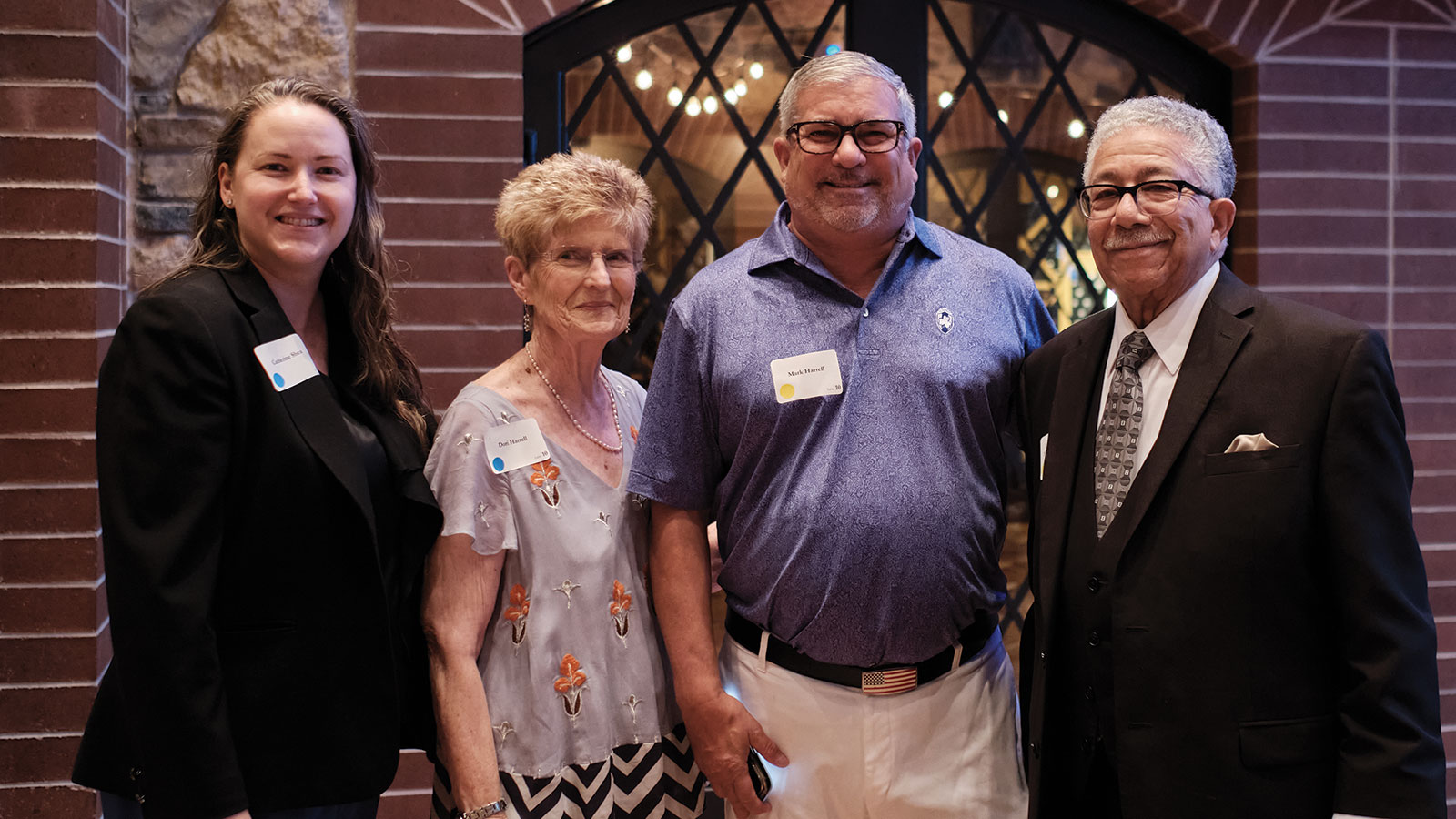

On September 25, approximately 250 lawyers, family members, justices, judges, magistrates, and law students gathered at the University of Denver to honor the great litigator Irving P. Andrews with the dedication of the new Irving P. Andrews Inn of Court. The newly named Inn of Court will focus on family, juvenile, and probate law. Highlights of the event included speeches from retired Denver County Court Judge Alfred Harrell, who is one of Irving’s children, and retired District Court Judge John L. Kane, who was Irving’s law partner for a time. Judge Kane’s moving tribute to Andrews is reprinted here with permission.

Remembering Irving Andrews, by John L. Kane

When one describes a person, it is essential to place him in the context of the society in which he lived. Had he been born and lived in a different era, Irving’s life and character would not have been the same.

Irving Piper Andrews was born on October 12, 1925, in Denver, Colorado, to Irving Piper and his wife, Myrtle Stanley. His father had been a soldier in World War I and was severely injured by mustard gas. He died when Irving was very young, and Myrtle later married Hulman Andrews, who adopted Irving and changed his name to Irving Piper Andrews. By the time he was 4, the stock market collapsed and the Great Depression began. Hulman moved with his wife and son to Pueblo, where he worked for the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company cleaning out the blast ovens.

Another significant event happened when Irving was a preschool child. The family lived in a predominantly white neighborhood close to the steel mill. One day he came crying into the family home and told his mother that the white children on the block refused to play with him. His mother placated him and said, “This will pass. In the meantime, you know how to read and there is a library at the other end of our block. You go there and read.” The library became his refuge, and he became a voracious reader, quickly surpassing the reading level expected for a child of his age—and forever grateful for enthusiastic librarians.

Irving then attended local public schools. He was an excellent student who found solace in his frequent isolation by continuing to read, as always far above his grade level. After graduating from high school in 1942 at age 17, he was drafted into the US Navy.

During World War II, many Black Americans were assigned by the Navy to work in the food and cleaning services. But Irving could read at an advanced level and also use a typewriter, so he was classified as a yeoman, which is Navy talk for someone who performs clerical duties. Irving was assigned to an intelligence unit and served in the South Pacific.

Because his work involved handling classified intelligence information and communications, he was not permitted to live with non-intelligence unit sailors. He was isolated. He read everything he could get his hands on.

At the end of the war, Irving was honorably discharged and attended Colorado College on a scholarship. He majored in history and economics and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. While an undergraduate, Irving met A. Edgar Benton, and together they formed a championship debating team that competed on an intercollegiate level. They were successful, formidable, and admired debaters.

After three years at Colorado College, Irving moved to Denver and enrolled at the University of Denver College of Law, in part financed by the GI Bill. While at DU, Irving worked at the Glenarm Branch of the YMCA as a custodian. The Glenarm Branch was in the heart of the Five Points area, which consisted almost exclusively of Black residences and businesses. Denver was segregated, and Black people were not permitted equal access to establishments, services, or industry.

In 1950 Irving graduated and passed the bar with flying colors, yet he could not find employment either in private law firms or government agencies. The white law firms did not hire minorities or women as lawyers, nor did the City and County of Denver. The few Black lawyers in private practice were solo practitioners who were not engaged in hiring newly admitted lawyers.

Irving continued working as a custodian and took what few cases or clients came his way. He was eventually able to devote all his energy to the practice of law, mostly defending criminal cases. At that time, there were no public defender offices in the state and the Legal Aid Society struggled to handle a limited docket on a very limited budget.

In no small measure, Irving’s practice grew because of referrals and assistance he received from two white lawyers, Marilyn and Harold Meadoff. His court appearances increased, and he obtained an office. Later, he shared his office with Robert Rhone, another Black lawyer who was also a Colorado state legislator.

In 1962, Bob Rhone died from a blood clot in his leg. Shortly thereafter, I joined Irving, and we formed a partnership. It was the first racially integrated law partnership in Colorado. By then, his practice was busy, and he was recognized as one of the area’s leading criminal defense attorneys.

Irving was very active in the civil rights movement. He held office in the NAACP and as a pro bono member of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. He represented other civil rights organizations and defended civil rights workers and volunteers charged with various offences for participating in nonviolent protests.

Throughout his career, Irving Andrews combatted segregation. He was on the national team of lawyers who reviewed, collaborated, and critiqued the briefs filed in the Supreme Court case of Brown v. Board of Education. He organized peaceful demonstrations and participated in the 1963 March on Washington with Martin Luther King Jr.

On a more personal basis, Irving and his family were pioneers in integrating the formerly all-white subdivisions in Southeast Denver. Yet he maintained his law practice in the traditionally Black neighborhoods in Central Denver. The core of his commitment was to end racism by ending segregation and developing integration nonviolently through negotiation, litigation, and personal example.

In 1908, a group of activists issued a call in the wake of yet another eruption of anti-Black violence for a national meeting to discuss racial justice and an end to street violence and lynchings. From that meeting, the nation’s largest and most widely recognized civil rights organization, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, was born on Lincoln’s Birthday, February 12, 1909. Other movements organized and dedicated themselves to the pursuit of racial justice, but the NAACP was specifically channeled to end racial segregation and advance non-discriminatory integration by means of litigation and legislation. Irving believed to the marrow of his bones in these principles. He abhorred violence and thought it was counterproductive to the success of the civil rights movement. His dedication to the NAACP and its ideals was unwavering.

Although some in the civil rights movement thought that more direct action was needed, the NAACP maintained its focus on litigation and cooperated with organizations practicing more active protests by providing legal representation and bail to those who were arrested. The organization also filed numerous civil cases against states, local governments, and individuals who supported segregation and repression such as Jim Crow laws, policies, and practices. Irving was steadfast and unwavering in this endeavor. Irving died on June 18, 1998, at age 73 from complications accompanying a prolonged respiratory illness.

That is a very brief biography of Irving Andrews, but what made him such a formidable advocate and memorable lawyer was not merely that he loved the law and knew it well. The same can be said of many. What is most notable about him is that he gave more to advocacy than he took from it.

The basics of law are taught in the law schools, and they are essential for any area of practice. They are the tools one must learn to use, honor, and master, but the practice of trial law and advocacy is craft, and if practiced with diligence can occasionally become an art. It is what lawyers bring to this craft rather than take from it that separates champions from mediocrities. This purpose is the very essence of the American Inns of Court.

When Irving and I practiced together we seldom discussed cases or statutes. What we did discuss more often than not were concepts and ideas spread throughout the broad range of his knowledge of history, literature, philosophy, and rhetoric. Irving recognized that using the language, syntax, and vocabulary learned in law school was incomprehensible to most jurors, witnesses, and clients. He knew and taught that “the law” was not a synonym for “justice” and that these nonlawyers expected justice, not legal sophistry. Our basic intent was to understand concepts and put them into context with words that jurors and other people not trained in the language of the law could make sense of.

The first subject we approached was “justice,” and our first study was the best book on the subject, Plato’s Republic. We read it in conjunction with Aristotle’s Rhetoric and related both to courtroom performance. I say “performance” because Irving rightly conceived of advocacy, both in trials and negotiations, as a form of theatre. In a meeting or a jury trial, the presentation must be designed so that a group, bound together for the duration, will act as a group rather than as confused individuals, and they will act on the basis of what they collectively believe is true. At the core of Irving’s belief is that a fact or a statement is true if it can be incorporated in an orderly and consistent way with the body of knowledge and wisdom that people of ordinary experience understand and accept.

We also read and discussed many of Shakespeare’s plays. During his periods of separation, Irving had read them all. He taught me not only about Shakespeare’s views about character, but also to listen for not only what is said, but what is omitted. Most importantly, communication is exercised through a kind of theatre. In planning a trial or other juxtaposition of events over which an advocate does not have total control, one can learn from stagecraft, acting and directing how to shape one’s message or argument. The art is to structure the truth one seeks when the decision is made by others. It wasn’t necessary or even advisable to quote Shakespeare, but rather to understand the structures and elements of his organization.

We also studied Aristotle’s logic beginning with his Organon. Aristotle asserted the basic structure of language provided the first step in understanding logic. He formalized fallacies into 13 categories and demonstrated how each was to be recognized to distinguish truth from error. These principles form the basis of persuasive argument and sustainable objections. His master work, Rhetoric, is the capstone.

Moreover, employing logic to analyze conflicting data and principles is essential to the lawyer’s life; it is the entree, the commencement. It is the acquired skill that enables one to grasp the heft and feel of how others will appreciate the same facts and principles.

I don’t think it is possible to “sum up” the life and contributions of Irving Andrews. What I can say that alone makes him so deserving of the honor to have this Inn of Court bear his name is that he developed and shared an aesthetic perception that enables one to grasp and master how others will appreciate the same facts and principles that lead us to justice.

The very first step in this process is to recognize the suffering of those who are subject to injustice. To do so requires imagination and a pervasive understanding of human nature. Injustice raises its ugly head whenever the illusion of equality is shattered, whenever rules are applied differently for one than for another, whenever false statements are made with utter disregard of the truth, and whenever intent is bereft of compassion.

This I assert is the legacy of Irving Piper Andrews.