Legal Deserts, Diversity, and Access to Justice

January/February 2026

Download This Article (.pdf)

Welcome to the new year. I hope all CBA members had a wonderful holiday and will have a productive and fulfilling 2026 in the practice of law.

As noted in my inaugural President’s Message, one of my goals this year is to address the growing crisis of legal deserts in Colorado. This work is a critical component of narrowing the access to justice gap in our state.

Legal Desert Defined

A “legal desert” is a geographic area where residents have severely limited access to legal services, often due to factors like low population density and a lack of incentives for attorneys to practice there. These regions—often rural or economically disadvantaged—either have no attorneys or too few attorneys to address the everyday legal needs of the community. A 2020 report by the American Bar Association (ABA) found that 1,300 county or county equivalents in the United States had less than one attorney per 1,000 residents, thus meeting the ABA’s definition of a legal desert.1 And many of these communities had no attorneys at all.2

In 2021, the Legal Services Corporation formed the Rural Justice Task Force to examine the challenges that rural Americans face in getting assistance for their civil legal problems.3 The key findings were summarized in an October 2025 report.4 Notably, the task force found that low-income households in rural communities did not receive any or enough legal assistance to resolve 94% of their legal problems.5 Moreover, the severe shortage of lawyers made it difficult for rural Americans to understand whether their everyday problems—financial, housing, health-related, and so on—were legal in nature.6 According to the report, “This lack of access not only hides legal issues in plain sight, it also contributes to a sense that the legal system is out of reach, eroding trust in the justice system itself.”7

Colorado’s Legal Deserts

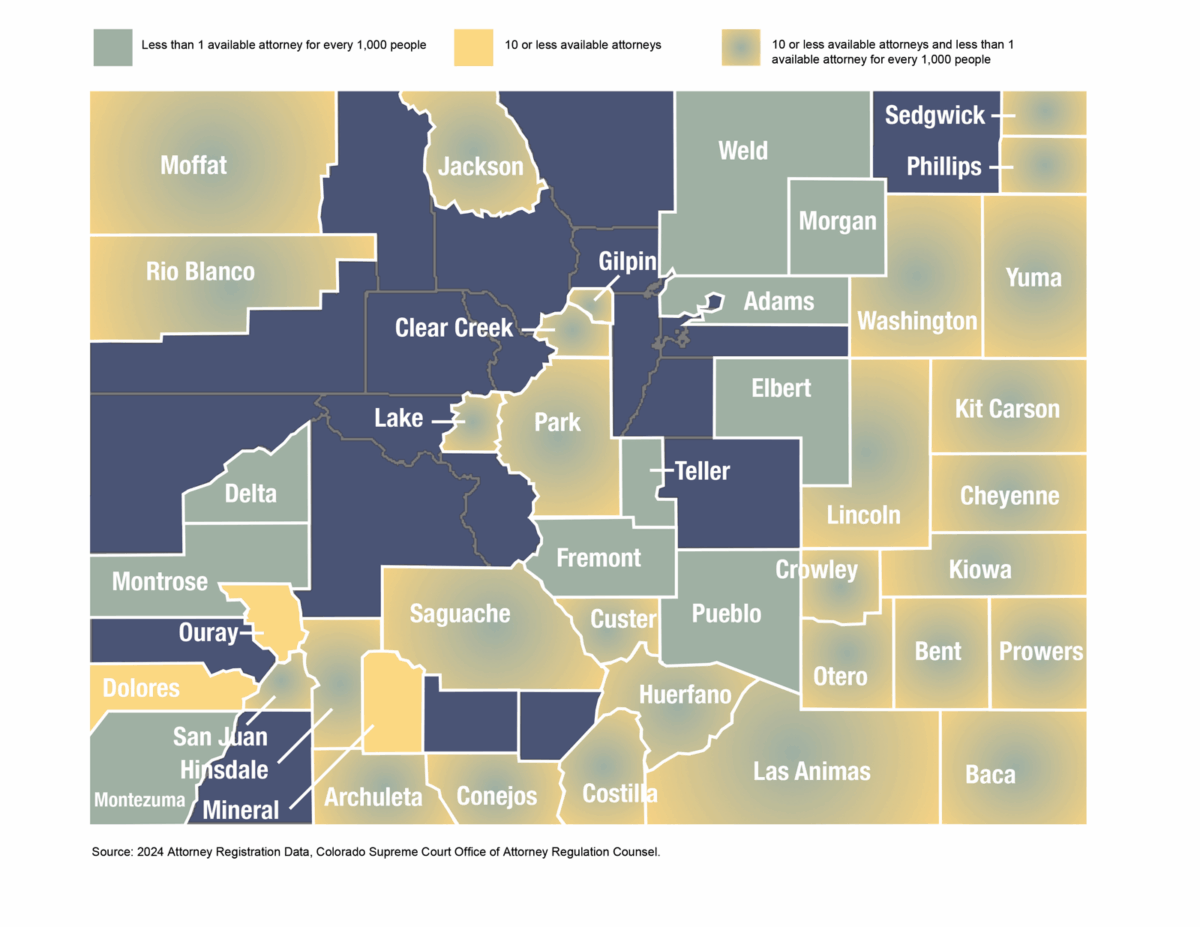

Legal deserts exist in nearly every state, and Colorado is no exception. In fact, a map compiled by Jason Roberts, director of Rural Legal Services for the Colorado Access to Justice Commission (ATJC), shows that 32 of Colorado’s 64 counties have fewer than 10 available attorneys. “Available attorneys” are defined as the attorneys in a county who could presumably provide civil legal services after removing judicial department, state, and county employees. Twenty-nine of those counties also have fewer than one available attorney per 1,000 residents, and another eight have less than 1.5 available attorneys per 1,000 residents. That means that more than half of Colorado’s counties are either legal deserts or are on the verge of becoming a legal desert.

Why Legal Deserts Exist

Legal deserts exist for a variety of reasons. Many rural areas simply lack the population base needed to support a law practice, and geographic barriers can make it difficult for lawyers to meet with clients or travel to court. In some communities, long-time attorneys are retiring with no new lawyers to take their place. New graduates may struggle to settle into small towns, and traditional legal education often leaves them underprepared for launching and sustaining a solo or small practice in rural settings. Many law students are also unaware of how significant the need for legal services is in these regions.

Additional barriers to rural practice include high housing costs, limited broadband or cell coverage, and the heavy burden of law school loans. Recent studies report that the average law school graduate has accumulated roughly $150,000 in debt.8 Large metropolitan firms can offer salaries that make repaying this debt more manageable, whereas joining or starting a small practice in rural Colorado makes debt service far more challenging. Although the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program provides loan forgiveness after 10 years of qualifying public service, it does not extend to private attorneys who wish to practice in rural areas.

Access to Justice and Diversity in Rural Colorado

The consequences of legal deserts go beyond limited access to legal advice. When few attorneys live and work in rural communities, the pipeline for future public defenders, prosecutors, county and municipal attorneys, and applicants for county and district judgeships weakens. Without that pipeline, attracting qualified candidates—particularly those who reflect the diversity of Colorado’s population—becomes more difficult.

The statewide legal community has taken meaningful steps to address this challenge at the judicial level. In 2019, for example, the CBA and the Colorado Judicial Institute partnered to create the Diversity on the Bench Coalition to help recruit, retain, and support a diverse bench across the state.9 And in 2020, the Colorado Judicial Department’s Judicial Officer Outreach (JOO) Program was established within the Office of the State Court Administrator to help cultivate a state court bench that reflects the diversity of the communities it serves.

Results of these efforts have been encouraging. According to the JOO Program’s 2024 report, between July 1, 2023, and June 30, 2024, 27 new judges were appointed, 14.8% of whom identified as judges of color. And as of October 1, 2024, 17.94% of all Colorado judges self-identified as judges of color or as belonging to two or more races.10

Colorado’s Access to Justice Commission

Formed in 2003 with the support of the Colorado Supreme Court, the CBA, and the Statewide Legal Services Group, the ATJC works to create solutions for those who lack the information, tools, and services necessary to resolve their civil legal problems fairly, quickly, and economically. One of its flagship initiatives, the Rural Justice Internship Program, introduces law students to legal practice in rural Colorado communities.11 The first year of the program is a summer internship that offers students the opportunity to live and work in one of six sites across the state through a combined judicial and private-practice or public-interest internship. Interns gain a unique blend of experience by spending time both in the courts and with a local community partner. Interested students can return to their site community for a second-year internship that focuses on building practical skills and professional networks to support students as they begin their careers in rural Colorado.12 Each intern receives a $5,000 stipend to help offset living and transportation expenses. The hope is that these students will return to rural Colorado to practice after graduation.

Efforts Outside Colorado

Jurisdictions nationwide have been experimenting with strategies to recruit and retain rural lawyers. Most of these programs involve early student outreach, financial incentives, mentorship, rural placements, and coordinated partnerships.13

In 2013, South Dakota established a first-of-its-kind program in the United States designed to address the shortages of lawyers in rural areas by offering financial incentives.14 Qualifying attorneys receive an incentive payment in return for five continuous years of practice in an eligible rural county (population of 10,000 or less) or municipality (population of 3,500 or less). Attorneys must enter into a contract with the Unified Justice System (courts), the state bar, and the eligible county or municipality. Program participants receive five annual incentive payments of $12,513.60 per year (equivalent to 90% of one year’s resident law school tuition and fees)—a total of $62,568 over five years. As of June 30, 2025, a total of 36 attorneys have participated in the program, with 19 completing their five-year commitment and 14 choosing to remain in their rural communities.15

Several other states, including North Dakota, Illinois, and Nebraska, have started similar programs. The University of Georgia School of Law offers scholarships and summer stipends for students interested in rural practice, and the University of Alabama Law School’s Finch Initiative provides fellowships for law students to experience small-town legal work. The National Center for State Courts is also addressing the needs of rural communities.16

But budget shortfalls and political resistance to these programs present challenges to the creation of additional similar programs in other areas of the country.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The challenge of ensuring adequate legal services in rural Colorado is complex, multifaceted, and increasingly urgent. Yet meaningful progress is possible. By continuing the work of the ATJC and possibly establishing a new Colorado Rural Legal Task Force that brings together judges, attorneys, law school leaders, and state and local policymakers, Colorado can develop coordinated and sustainable solutions. Although funding remains a persistent obstacle and the state faces another significant budget shortfall, the need to invest in innovative incentive programs that attract new law graduates to rural communities is critical. The longer we wait, the more difficult and costly the problem will become.

Notes

1. ABA, ABA Profile of the Legal Profession 2 (2020), https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/news/2020/07/potlp2020.pdf.

2. Id.

3. Legal Services Corporation, Justice Where We Live: Promising Practices From Rural Communities (Oct. 2025), https://lsc-live.app.box.com/s/mv52lja5n42j9auu0pywl07ozkzgvm6d.

4. Id.

5. Id. at 6.

6. Id. at 7.

7. Id.

8. See, e.g., ABA, supra note 1 at 25 (“The median cumulative debt at law school graduation among those who completed the survey—for law school, undergraduate and other education expenses—was $160,000. That is close to the national average of cumulative debt for all law school graduates of $145,500 in 2016, according to the U.S. Department of Education.”).

9. “Diversity on the Bench Coalition,” https://www.cobar.org/For-Members/Diversity-on-the-Bench.

10. Colorado Judicial Department, Judicial Officer Outreach Program FY 2024 Annual Legislative Report, https://coloradojudicialinstitute.org/file_download/inline/492696d6-6895-41ce-95c1-b3aa6cb2a126.

11. ATJC, Rural Justice Internships, https://www.coloradoaccesstojustice.org/rural-justice-internships.

12. The Year 2 program pilots in 2026.

13. Committee on Legal Education and Admissions Reform (CLEAR) Report and Recommendations (July 27, 2025), https://www.ncsc.org/libraries/mozilla-pdfjs/web/viewer.html?file=https://www.ncsc.org/sites/default/files/media/document/CLEAR_Report.pdf.

14. South Dakota Unified Judicial System, “Rural Attorney Recruitment Program,” https://ujs.sd.gov/for-attorneys/rural-attorney-recruitment-program.

15. Haksgaard, The Rural Lawyer: How to Incentivize Rural Law Practice and Help Small Communities Thrive at Ch. 6 (Cambridge University Press 2025).

16. National Center for State Courts, “Rural Justice,” https://www.ncsc.org/resources-courts/access-fairness/rural-justice.