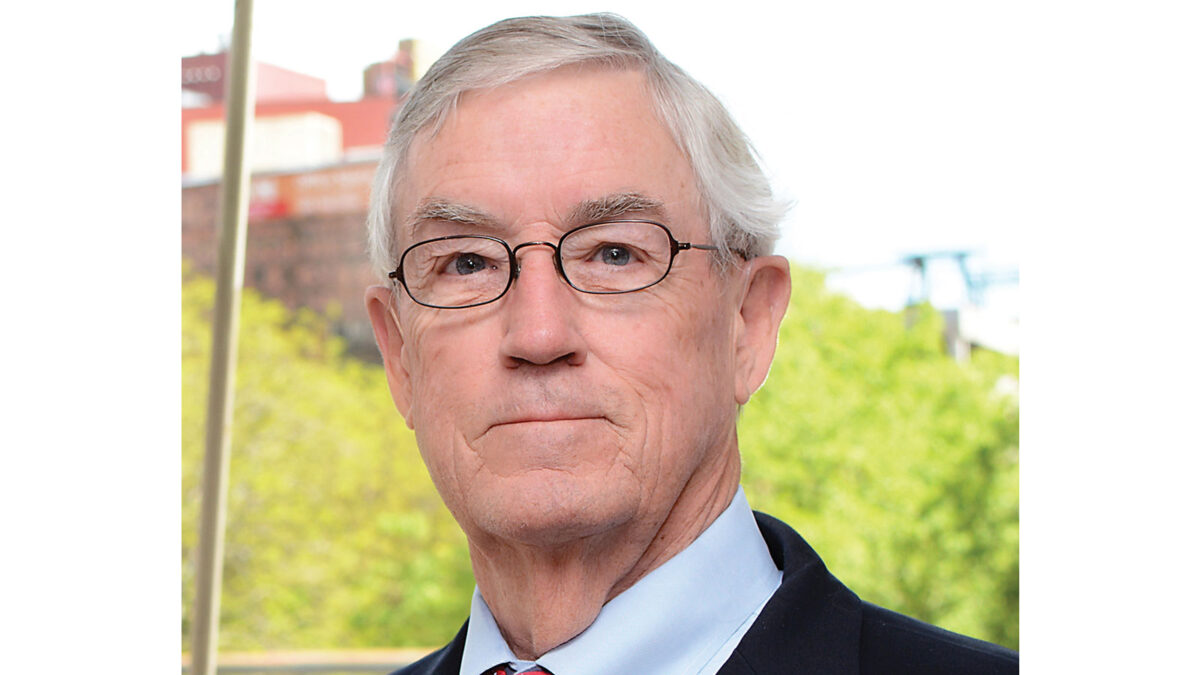

Richard P. Holme

(1941–2023)

May 2023

Download This Article (.pdf)

At any given moment in Colorado legal history, a small handful of practitioners come to define their generation. Richard P. “Dick” Holme, whom the Colorado legal community sadly lost on January 14, 2023, was one such lawyer, and his passing affords an opportunity to reflect on—and celebrate—a truly wonderful life in the law.

Early Years and Law Practice

Dick was born in Denver on November 6, 1941, to Peter H. Holme Jr. (a Colorado legal legend in his own right) and Lena Holme. Dick graduated from East High School and then from Williams College, where he received his BA in 1963.

After graduating from college, Dick went on to law school at the University of Colorado. There, he served as the managing editor of the law review and ultimately graduated with honors in 1966 as a member of Order of the Coif. While in law school, Dick met the love of his life, Barbara Friel, and the two married in 1965, beginning a partnership that would endure for 57 years and that would produce two sons, Daniel and Robert, and a “marvelous” grandson, Jaxson.

Dick passed the bar shortly after graduating from law school and joined the law firm of Davis Graham & Stubbs as an associate in the litigation department. Dick worked there for three years but left to join the Denver District Attorney’s Office, where he served for three years and tried dozens of jury trials.

Thereafter, in 1969, Dick returned to Davis Graham, where he would remain as a partner for over 50 years, until he transitioned to senior of‑counsel status. During his many years at the firm, Dick distinguished himself in a broad‑ranging commercial litigation practice. He handled complex commercial litigation matters, including a commodities fraud case involving hundreds of investors and claims that approached $100 million in losses. He represented clients in class action suits involving widespread environmental contamination. He litigated arbitrations involving patent claims, employment matters involving damages into the eight figures, and a wide array of trade secret, product liability, and securities fraud matters. He took the lead in many significant media, First Amendment, and other constitutional law disputes. And he briefed and argued a wide array of appeals not only in Colorado but also in courts throughout the country. All told, Dick tried almost 70 jury trials (including those while he was a deputy district attorney), as well as numerous bench trials and arbitrations.

During his long and impressive career, Dick was a quintessential lawyer’s lawyer. He was a remarkably skilled advocate, and he was unafraid to think outside the box. For example, in a time when few lawyers would forgo deposing the other side’s expert, Dick realized that such depositions often helped the expert more than Dick’s client (e.g., by providing a roadmap of Dick’s cross‑examination at trial). So, Dick would save his questions for trial, where he would inevitably conduct a withering cross‑examination for which the expert was unprepared.

Dick, however, never confused tenacity as an advocate with overzealous or unprofessional behavior. To the contrary, he was ever‑professional, and his unimpeachable integrity and credibility preceded him wherever he went. Dick always understood that his litigation adversaries were just that—litigation adversaries who were still professional colleagues. As a result, Dick made it a practice to take his opposing counsel for coffee or lunch at the beginning of a case, and he taught lawyers whom he mentored to do the same. Dick also would tell his adversaries that in the event of a dispute or disagreement, they should simply pick up the phone and call him, instead of writing a demand letter or filing a motion. Dick told his adversaries that he was more than willing to negotiate any dispute, and he meant it. And when an opponent called to discuss a disputed matter, Dick was always calm and gracious, paving the way for a speedier and less expensive resolution for all of the parties.

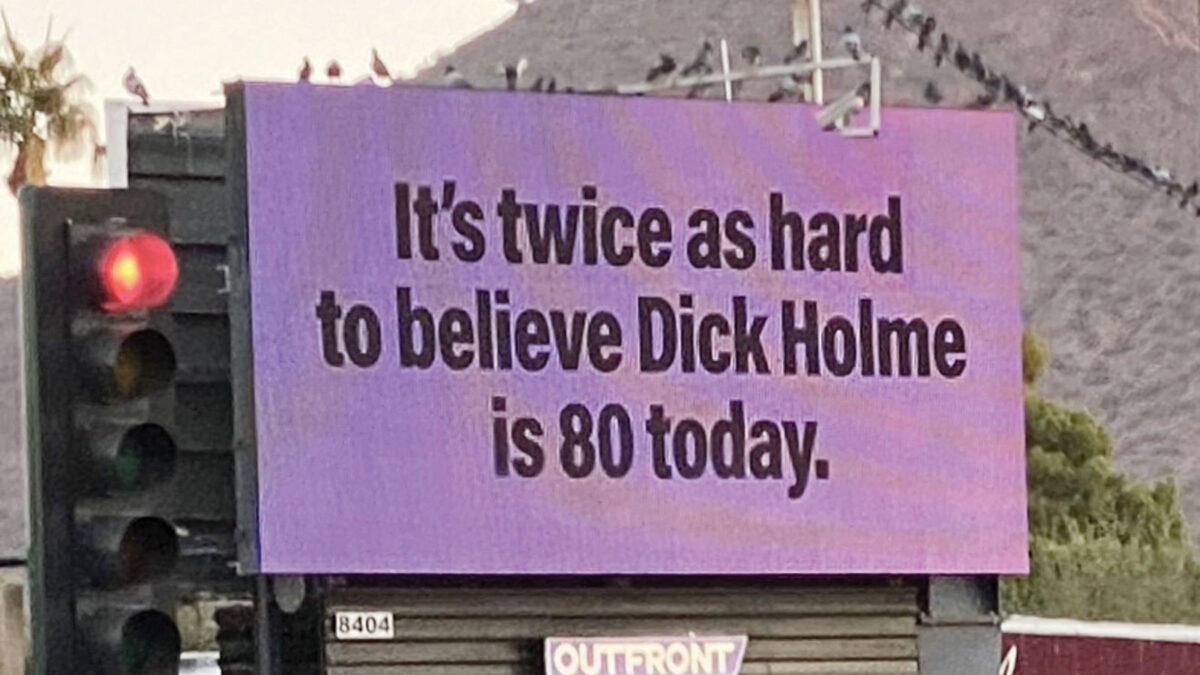

For Dick, and for other titans of the bar like him, professional behavior was always a strength, not a weakness, and the many successes in his career proved that point. No wonder that when Dick turned 80, an advertising client of his put up a billboard to wish him a happy birthday, just as the client had done for Dick’s 40th birthday!

A Lifetime of Service

True to his commitment to professionalism in the practice of law, Dick’s long career embodied service—to his colleagues, to the bench and the bar, and to our community as a whole.

To a person, Dick’s peers and colleagues describe Dick as a mentor in every sense of the word. His door was always open to partners and associates alike, and he relished the opportunity to work with colleagues to sort through difficult problems and to provide wise counsel whenever he was able. And this willingness to help was not limited to cases on which Dick happened to be working. All of Dick’s colleagues knew that he was available to them, whether he was working with them or not, and Dick always gave generously of his time.

Dick’s mentoring, however, went beyond just counseling, advising, and teaching. He knew well that a good mentor is also willing to promote and sponsor their mentees, and Dick routinely did so with remarkable selflessness. Dick’s former law partner Andy Low described how, early on in Andy’s career, Dick brought him on as “second chair” for a major media client of Dick’s. From the very beginning, Dick pushed Andy to the forefront of that client relationship, ultimately ceding lead responsibility for the client to Andy. Many senior partners, and particularly many in today’s competitive legal environment, would have jealously held on to that client relationship. But that was never Dick’s way, and his generosity in this regard guaranteed that his long‑established client relationships would continue to benefit his firm and his colleagues for many years to come.

Dick also understood the importance of diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility long before those concepts came to the forefront of other lawyers’ consciousness. When Charles Casteel joined Davis Graham in 1974, he was one of the very few young Black attorneys in any major law firm in the country, much less in Denver. Dick recognized the immense talent that Charles brought to the table, and Charles has shared how Dick “took a genuine interest in assuring [Charles’s] comfort and success as a young Black attorney entering the practice of law at the dawn of integration in Denver’s legal community.” For Dick, this was not just a polite gesture. Dick maintained his personal interest in Charles’s career throughout, and the two became not merely law partners but lifelong friends.

Dick had the same type of relationship with Kenzo Kawanabe, who joined Davis Graham at a time when the firm, like many others, had no Asian American partners. True to form, Dick took Kenzo under his wing, and Kenzo credits Dick’s “many acts of kindness and inclusion” with helping him achieve so many of his successes in the practice of law.

Dick’s entire legal career was about serving our profession—always for the right reasons. Dick’s lifelong efforts to improve trial practice and the practice of law generally included his many leadership positions for both the Colorado and Denver Bar Associations, his work as a member of the Colorado Supreme Court’s Grievance Committee, and his 30 years of work as a hearing board member and mediator in disciplinary matters. But Dick was not satisfied with just those extracurricular activities, which would have amounted to a second full‑time job for many lawyers. Dick also served on innumerable standing committees for the Supreme Court, the bar association, the American College of Trial Lawyers, and the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System. This work included serving as a member of the drafting committee for Colorado’s Criminal Code, the first Colorado Jury Instruction Committee, the Supreme Court Nominating Commission, and the Supreme Court’s Civil Rules Committee. Notably, Dick served on the Civil Rules Committee for over 25 years, and he was the principal draftsperson of the rules relating to simplified procedure and discovery practices, reflecting his deep‑seated interest in ensuring that the civil rules promoted and did not impede access to justice. And Dick did not stop when the rules for which he had advocated were adopted. To the contrary, he would inevitably step up to write an article for Colorado Lawyer introducing and explaining the new rules to the bench and the bar.

For these and his many other efforts on behalf of the profession, Dick received numerous awards and honors. He routinely was listed in Best Lawyers in America and Super Lawyers, and in 1983, he was elected a fellow in the American College of Trial Lawyers, serving as Colorado State Chair from 1994 to 1996.

“A Very Good Man”

Dick Holme, however, was far more than just a great lawyer who went above and beyond to serve the bench, the bar, and his community. When speaking about Dick, his friends and colleagues first describe his devotion to his beloved wife Barb and his family and then they almost immediately describe Dick as “a very good man.” Or as his longtime friend and colleague from the district attorney’s office, Chuck Kall, put it, “Dick was an outstanding lawyer but most importantly, he was a fine, first‑class honest man.” And Chuck was quick to add that Dick was also a “boon companion,” no doubt because Dick was a wonderful conversationalist who had an impish and often self‑deprecating sense of humor. One would see the real Dick Holme when he was performing with the Burden of Spoof musical comedy troupe, where he made a name for himself singing parody lyrics to, among other notable songs, the up‑tempo patter songs of Gilbert & Sullivan.

And Dick was not above bringing his wry sense of humor into the office. In 1979, when Davis Graham purchased its first computer, Dick circulated a memo, purportedly from the “Technological Committee,” announcing the “additional acquisition of technological devices,” namely, the Dixon Ticonderoga 1388. Touting the immense benefits of this remarkable device, Dick’s two‑page, tongue‑in‑cheek memo noted, “These instruments are compact enough to be hand held and can readily assist in the most complex calculations.” And the memo went on, “[T]he Dixon Ticonderoga 1388 can eradicate incorrect input on the part of the time recorder by a very simple manipulation that only requires turning the instrument upside down.” (For those who may have spent far too many years typing on a computer, the Dixon Ticonderoga 1388 is a pencil.) At least one senior partner totally fell for the gag. This magnificent piece of satire is a beloved part of Davis Graham lore, and thankfully, one of his colleagues still has a copy of the memo!

Conclusion

So, how does one sum up a legacy like Dick Holme’s? Sadly, but perhaps appropriately, it cannot be done in just a few words. Along with the late Dick Laugesen, Dick Holme could justifiably be deemed the father of the civil rules in Colorado. He could also justifiably be credited with almost single‑handedly revolutionizing civil litigation for parties, courts, and counsel alike, with his goal being to ensure that cases are tried well, efficiently, and economically, with the cost properly tailored to the breadth of the dispute. But perhaps most important, Dick Holme can and should be remembered as a very good man who, for over 50 years, practiced law the right way—and taught countless others to do the same. Those of us who counted Dick as a mentor, a role model, and a friend are perhaps Dick’s greatest legacy, and it is left to us to carry forward his incredible life’s work. We could provide no better tribute.