The Legal Profession’s Pyramid Scheme and Why It’s Worth Fixing

March 2024

Download This Article (.pdf)

The legal profession, often revered for its pillars of justice and advocacy, can also resemble a labyrinthine pyramid scheme. At its apex stand the established firms and high-profile attorneys, basking in the limelight of success and influence, while the base—a burgeoning multitude of aspiring lawyers—clamors to ascend, often encountering hurdles of debt, fierce competition, and elusive opportunities. The legal professionals who comprise this pyramid are not immune to the pressures and challenges it creates. It’s worth fixing this scheme to recognize the humanity of lawyers and empower them to thrive not just as legal practitioners but as individuals with multifaceted needs, emotions, and aspirations. By nurturing a supportive ecosystem and creating a new hierarchy of needs for lawyers, the old pyramid can be flattened to create a new professional culture.

The Legal Profession’s Pyramid Scheme

The legal profession is a pyramid scheme, where a select few at the top hold most of the power, while the majority at the bottom struggle. This type of professional structure can make it feel like lawyers have little control over their professional lives and that success is difficult to attain.

One of the key factors that perpetuates a pyramid scheme mentality in the legal profession is the idea that success as a lawyer is only attainable by climbing the rungs of the profession and achieving professional ranks such as partnership in private practice.

This idea is reinforced by the legal profession’s attachment to the “myth of meritocracy.” For many centuries, the legal profession has perpetuated the idea that everyone has equal access and opportunity to both enter the profession and climb to the highest ranks within the profession: the “smartest” and/or hardest working lawyers are the most successful because the system is predicated on an objective set of criteria by which everyone is judged, irrespective of gender, religion, race, or sexual orientation.

However, this pervasive belief fails to take into account that equally intelligent and qualified individuals (1) have access to different resources (e.g., internships through connections, hiring and/or promotions through friends or family); (2) face challenges of different sizes and frequencies along their education and career paths (e.g., no financial support during school, being the first person in the family to attend college or enter the profession, no mentors or allies in the workplace); and (3) face discrimination or bias.1

The profession’s reliance on evidence such as law school grades or law review participation as gatekeepers to employment has yet to be proven as a reliable measure of success as a practicing attorney.2 Additionally, this “equality” bias has the potential to frame any type of diversity negatively, as incorporating an “equity” based approach to hiring, promotion, and compensation is thought to come at the expense of excellent legal service instead of enhancing the quality of legal service.

Even as legal organizations are rolling out initiatives to address meritocracy bias, there has been little focus on addressing the historical systems of the legal profession rooted in informalism and exclusionism. These invisible forces lie below the surface of law schools and legal organizations, but they shape the cultural norms of the profession through unspoken or unwritten rules that impact lawyer satisfaction, advancement, and career trajectory. To get to the top of the profession’s pyramid, one must have access to and understanding of the informal rules that govern whether a lawyer is included or excluded from opportunity.

The Lawyer’s Hierarchy of Needs

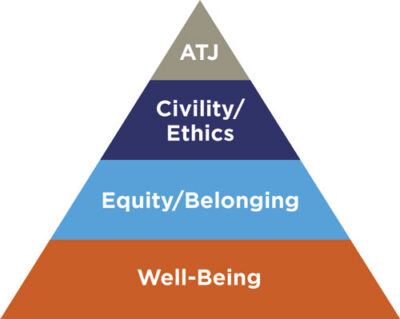

Much has been researched, written, and discussed about the challenges of the legal profession and how the systemic, structural, and cultural elements of the pyramid scheme make it difficult for some lawyers to find success. These well-documented “pain points” generally fall into four broad categories: access to justice, civility and ethics, equity and belonging, and well-being. When we consider these systemic challenges through a more human lens, we can design a different kind of pyramid for the legal profession. Instead of a pyramid scheme that only serves a few, we can design a new pyramid to serve everyone and to guide lawyers in a process of self-actualization to lessen the impact of the negative structures and cultures of the profession.

Using Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs3 as a guide, the professional challenges referenced above can be organized into a stratified context that provides a humanistic approach to the challenges of the legal profession. And just like in Maslow’s theory, each level of the hierarchy must be sufficiently met before a lawyer is prepared to tackle the next level.

Well-Being

The “Lawyer’s Hierarchy of Needs” begins with physiological and safety needs. The well-being of lawyers is a basic tenet of lawyer success and creates a humanistic approach that relies on six dimensions of well-being to focus on the whole lawyer:

- Occupational: Cultivating personal satisfaction, growth, and enrichment in work; financial stability.

- Emotional: Recognizing the importance of emotions. Developing the ability to identify and manage our own emotions to support mental health, achieve goals, and inform decision-making. Seeking help for mental health when needed.

- Physical: Striving for regular physical activity, proper diet and nutrition, sufficient sleep, and recovery; minimizing the use of addictive substances. Seeking help for physical health when needed.

- Intellectual: Engaging in continuous learning and the pursuit of creative or intellectually challenging activities that foster ongoing development; monitoring cognitive wellness.

- Spiritual: Developing a sense of meaningfulness and purpose in all aspects of life.

- Social: Developing a sense of connection and belonging and a well-developed support network while also contributing to our groups and communities.4

Equity/Belonging

The hierarchy then moves to needs of belonging, focusing on a lawyer’s inherent need for concepts like friendship, community, shared experiences, being valued for their uniqueness, and anything that gives lawyers a sense of belonging among themselves. Efforts in the legal profession to improve elements of diversity and equity have long focused on the need for and value of belonging in the success of lawyers. Research has shown that belonging and collegiality foster psychological safety—the feeling that the work environment is trusting, respectful, and a safe place to take risks. When lawyers don’t feel psychologically safe, they are less likely to seek or accept feedback, experiment, discuss errors, and speak up about potential or actual problems.5

Civility/Ethics

Just as in Maslow’s hierarchy, the lawyer’s hierarchy next considers “esteem” needs. In Maslow’s pyramid, esteem refers to a person’s sense of self and their sense of self in relation to others. This level includes things like dignity. In the legal profession, lawyers most often develop their sense of self and relate to one another through concepts of civility and professionalism, as well as their engagement with the Rules of Professional Conduct.

Civility has long been known to be a critical element of the successful practice of law and the self-actualization of lawyers. Lawyers who behave with civility report higher personal and professional rewards. Conversely, lawyer job dissatisfaction is often correlated with unprofessional behavior by other lawyers. In the 2007 Survey on Professionalism of the Illinois Supreme Court Commission, 95% of the respondents reported that the consequences of incivility made the practice of law less satisfying.6

Access to Justice

Finally, once a lawyer has everything they need to survive, function, and understand their position in the profession, they can enter the final portion of the hierarchy. Just as in Maslow’s pyramid, this level for lawyers focuses on self-actualization. Self-actualization can mean many things, but most examples center around a desire to explore, create, or expand one’s skills as a legal practitioner. In this sense, the practice of law is a critical component of the self-actualization of lawyers. The self-actualization of lawyers has a large impact on consumers and users of the legal system, as lawyers who cannot self-actualize cannot actively participate in the pursuit of access to justice.

Applying the Lawyer’s Hierarchy of Needs to Fix the Professional Pyramid Scheme

The Lawyer’s Hierarchy of Needs is a perfect paradigm for fixing the legal profession’s historical pyramid scheme. There are three ways the hierarchy can be applied:

1. Flatten the Pyramid

Modern law practice and the rapidly changing environment in which legal services are provided and consumed make it so that the people at the top of the pyramid can no longer pretend to have all the answers or to have all the skills to serve legal consumers. The diversity, creativity, and initiative of those lawyers at the bottom of the pyramid are essential to generate access to justice for legal consumers and improve satisfaction and experience in the profession for legal professionals.

2. “Empowerment” Is Not a Dirty Word

Flattening the pyramid and decentralizing power in the legal profession creates many benefits and challenges the professional status quo. When the hierarchies of the profession are disrupted, lawyers can break free from traditional constraints and be liberated to foster an environment where their voices, ideas, and contributions are valued. Empowering lawyers to contribute and participate in the legal profession in ways that meet their hierarchy of needs can only be seen as a positive.

3. Redefining “Social Value” in the Legal Profession

Social value is about understanding the relative importance that people place on changes to their well-being and using the insights we gain from this understanding to make better decisions.7 The legal profession has never been quick to focus on the social value of the lawyer’s hierarchy of needs. If we can better understand how lawyers are affected by the systems and cultures of the profession, we can understand the social value that our actions create or destroy for people. Redefining social value in the legal profession will make us more accountable for how lawyers’ lives are affected by our systems and cultures. Where the impact on people is valued and included in the decision-making process, we can create change for a more sustainable profession.

Conclusion

In the quest to reform the legal profession’s pyramid scheme, it’s imperative to embrace a paradigm shift toward the Lawyer’s Hierarchy of Needs. This innovative framework emphasizes the fundamental human aspects integral to lawyer success and fulfillment. By recognizing the diverse dimensions of well-being encompassing occupational, emotional, physical, intellectual, spiritual, and social facets, the legal profession can nurture a more holistic approach to lawyer growth. Prioritizing these foundational needs not only enables individual lawyers to thrive but also fosters a culture where inclusivity, belonging, and psychological safety flourish. Additionally, elevating the significance of civility and self-actualization within legal practice enhances both personal and professional satisfaction, transforming the legal landscape. Implementing this hierarchy isn’t merely a theoretical endeavor; it’s a transformative tool to dismantle the entrenched pyramid structure, empowering lawyers at all levels to contribute meaningfully, fostering innovation, and reshaping the legal profession into a more equitable and sustainable entity. Ultimately, by redefining social value and embracing this new paradigm, the legal profession can pave the way for a more resilient and human-centric future.

Related Topics

Notes

1. Intellectual Property Owners Association, “The Myth of the Meritocracy in Law Firms and Corporate Legal Departments” (2022), https://ipo.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Myth-of-the-Meritocracy-White-Paper.pdf.

2. Minority Corporate Counsel Association, “The Myth of The Meritocracy: A Report on the Bridges and Barriers to Success in Large Law Firms” (2003), https://mcca.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Book4-Purple.pdf.

3. Willingham, “What Is Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs? A Psychology Theory, Explained,” CNN.com (Aug. 15, 2023), https://www.cnn.com/world/maslows-hierarchy-of-needs-explained-wellness-cec/index.html.

4. Brafford, “Well-Being Toolkit for Lawyers And Legal Employers,” American Bar Association (2018), https://lawyerwellbeing.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Toolkit-Full_Final_July-30-2018.pdf.

5. Davis, “What Makes Lawyers Happy? It’s Not What You Think,” Forbes (Dec 19, 2017), https://www.forbes.com/sites/pauladavislaack/2017/12/19/what-makes-lawyers-happy-its-not-what-you-think/?sh=d8d8ed917e5e.

6. Reardon, “Civility as the Core of Professionalism,” American Bar Association (Sept 18, 2014), https://www.americanbar.org/groups/business_law/resources/business-law-today/2014-september/civility-as-the-core-of-professionalism.

7. Social Value International, “What Is Social Value?,” https://www.socialvalueint.org/what-is-social-value.