The Unique Legal Needs of Our Nation’s Military Service Members and Veterans

November 2022

Download This Article (.pdf)

The MVA Section’s attorney members and CLCV program volunteers practice across the spectrum of law. Although most legal practice for the military and veteran communities is the same as it is for civilians, unique military and veteran aspects exist within almost every legal practice area. To shed light on some of these unique issues, and to commemorate Veterans Day, several members of the section’s executive council have contributed to this month’s article:

- In part 1, LT Nicholas Monck, an attorney in the US Navy Judge Advocate General’s (JAG) Corps, addresses the role of JAG Corps attorneys in supporting the legal needs of active duty service members.

- In part 2, Sabra Janko, a solo practitioner and retired Army JAG, discusses several family law issues unique to military members, veterans, and their family members.

- And finally, in part 3, Michael McKenna, a retired Army JAG colonel and current Red Cross volunteer, provides a high-level overview of international humanitarian law and highlights a few lesser-known programs of the Red Cross.

Please note that the views and opinions presented in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of or imply endorsement by Department of Defense or its components.

Part 1: Representation for Active Duty Service Members,

by Nicholas Monck

Whether civil or criminal, simple or complex, or individual or part of a group, legal proceedings can be stressful for any party involved. When that party is a military member, that stress can affect not only the service member but also the unit. A service member involved in a court case or contract dispute may struggle to focus on the mission or training. That’s why the military understands that providing free legal aid to soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, and guardians is critical to maintaining military readiness and supporting national defense.

Whether civil or criminal, simple or complex, or individual or part of a group, legal proceedings can be stressful for any party involved. When that party is a military member, that stress can affect not only the service member but also the unit. A service member involved in a court case or contract dispute may struggle to focus on the mission or training. That’s why the military understands that providing free legal aid to soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, and guardians is critical to maintaining military readiness and supporting national defense.

JAG Corps attorneys, also known as judge advocates or JAGs, are available at bases and on ships around the world to serve the legal needs of the nation’s more than one million active duty service members and their dependents. From family law to landlord-tenant disputes to criminal defense, JAGs help military personnel navigate the legal system worldwide.

The JAG Corps traces its lineage to the appointment of Lieutenant Colonel William Tudor as the first judge advocate of the Army by the Second Continental Congress in 1775. During World War II, some 2,000 attorneys served in legal billets throughout the conflict. Though military lawyers had long provided some legal services to troops, in 1984 Congress formally directed all the JAG Corps communities to provide legal assistance to active duty service members, along with their traditional role of advising commanders on the law of war and rules of engagement.1 As active duty service members themselves, JAGs understand the unique complexities of military lives and are better able to serve the needs of fellow military members, particularly in remote or overseas locations.

Since the formalization of JAG Corps’ legal assistance role, family law has been at the forefront of legal services offered.2 Estate planning and marriage dissolution are the two primary practice areas, but judge advocates also assist with adoption, immigration, and child support cases.

Aside from domestic matters, JAG Corps attorneys play a critical role in helping service members assert their rights under the Servicemembers Civil Relief Act (SCRA).3 This law provides certain legal protections to those serving in the military on active duty orders. Notably, SCRA permits service members to break residential rental agreements, vehicle leases, or cell phone contracts without penalty when they receive permanent change of station orders.4 JAGs regularly advise on SCRA rights and help service members prepare the required documents.

Additionally, one of the most common legal services that judge advocates and military paralegals provide are powers of attorney for deploying or moving service members. The House Armed Services Committee Report that accompanied the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1994 acknowledged the importance of these documents:

The past experience of service members and their dependents who executed powers of attorney in advance of recent military operations has shown that some states and territories have refused to honor those powers of attorney because they were not executed in accordance with state or territorial legal requirements. The failure to honor these documents has created substantial hardships for military families.5

Judge advocates can counsel service members on the pros and cons of powers of attorney, draft these vital documents, and then notarize them. Critically, 10 USC § 1044b exempts military powers of attorney documents from any form, substance, formality, or recording requirements specified by state law, and requires a military power of attorney to be given the same legal effect as a power of attorney executed according to state law.6

Judge advocates can also provide limited scope representation and help service members litigate minor civil disputes. Predatory lending, vehicle lemon law, small claims, construction defect, taxes, and name changes are just a few of the legal issues JAG Corps attorneys advise on7

When a military base is impacted by a natural disaster, the JAG Corps will send a unit of specially trained legal assistance attorneys to assist military families with claims paperwork. JAGs also support units and ships preparing to deploy by providing legal briefs and helping service members get their personal affairs in order.

Additionally, JAGs counsel service members who are under investigation or accused of misconduct. Similar to the civilian system, a service member has the right to remain silent and the right to consult with an attorney during an interrogation. If criminal charges are brought against a service member, a JAG Corps defense attorney will be assigned to represent them free of charge at a military court-martial. Many service members are also entitled to JAG Corps representation during an administrative separation board, which can separate them from the military for minor or non-criminal misconduct.

Whether assisting pilots, radio operators, or riflemen, judge advocates handle the many legal needs active duty service members face every day. From Bahrain to Germany to Colorado, they provide a global force to serve those who have been called to serve their nation.

Part 2: Family Law Issues Unique to Service Members and Veterans,

by Sabra Janko

Where service members and veterans are involved, federal law occasionally governs matters traditionally governed by state law. This is because (1) service members and veterans often receive payments that are federally governed, (2) the military system itself offers quasi-judicial remedies, and (3) military members may reside on installations under federal jurisdiction or overseas. This creates some unique considerations for family law attorneys assisting service members, veterans, and their families. Several key areas are discussed below.

Where service members and veterans are involved, federal law occasionally governs matters traditionally governed by state law. This is because (1) service members and veterans often receive payments that are federally governed, (2) the military system itself offers quasi-judicial remedies, and (3) military members may reside on installations under federal jurisdiction or overseas. This creates some unique considerations for family law attorneys assisting service members, veterans, and their families. Several key areas are discussed below.

Military Disability Payments

Once their service is complete, those who have served in the military can apply for a Veterans Administration (VA) disability rating based on service-connected disabilities. The VA disability rating differs from a Social Security disability rating, which is based on a negative impact on a person’s current ability to work in the national economy. There are military veterans working full time with a 100% VA disability rating.

The rating and its associated tax-free pay are intended to compensate veterans for physical or mental disabilities stemming from their service to their county. For example, combat veterans sometimes experience post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) related to their combat service. The rating compensates them for the disability but does not indicate their inability to work in the national economy. While military retirement pay is taxable by the federal government, disability pay is not.8 State regulations differ with regard to taxation of military retirement pay.9

Disability pay is considered income for purposes of spousal and child support.10 However, the disability portion of a military retirement is not considered a marital asset that can be divided upon dissolution11 A retiree who has a 40% disability rating or lower may waive a portion of military retirement pay to receive tax-free disability payments in the waived amount.12 In Colorado, courts cannot indemnify a spouse for the waiver portion through other means.13

Child or Spousal Support Payments

The military system offers quasi-judicial remedies not available in the civilian sector. For example, a practitioner familiar with the military system can help a military spouse obtain spousal and child support without ever setting foot in court. Each military branch has regulations requiring service members to support their dependents. Should a service member not meet this obligation, remedy can be obtained through the military Inspector General system. The Inspector General offices receive and process reports of a failure to support military dependents. The regulations exist in part because military members receive financial payments for their dependents.

Generally, a complaint of nonsupport to an Inspector General’s office results in a referral to the service member’s miliary commander, who is required to timely investigate the matter and determine whether support is warranted.14 If so, the commander is required to counsel the service member on their requirement to pay. Each service has a regulation setting forth the amount the service member must pay.15 For example, for the Army, this regulation is Army Regulation 608-99. In almost all circumstances, if the commander counsels the service member on a requirement to pay, then payment is made. Military commanders may take negative personnel actions against service members who do not pay their just debts. The regulation payments are intended to be a temporary remedy until the parties either enter into a consensual agreement or a court order issues. However, the payments stay in place until a support agreement is entered into, a court support order is issued, or the parties’ marriage is dissolved.16

Service of Process

While service of process is the same for military members residing off-post domestically as it is for civilians, it differs for military members residing on-post or overseas. For on-post service, it is relevant whether the land is under federal or concurrent jurisdiction.17 For example, the main part of Fort Carson, where the living quarters and offices are, is under exclusive federal jurisdiction. Here, the Army will determine whether the military member consents to accept service of process and, if so, will cooperate to effect the service. Service members who do not consent to service of process cannot be served on this part of Fort Carson. The Provost Marshall’s Office is the main point of contact for service on Fort Carson.

However, some military bases have concurrent jurisdiction where jurisdiction is both federal and state. Here, there are no restrictions on serving the military member. Examples are the Air Force Academy and some training areas on Fort Carson. Difficult service issues can be avoided if the military member is willing to sign a waiver of service.

Service of process when military members are stationed overseas can be more difficult. If the service member will not consent to service, then the next best step is for the filing party to arrange with someone whom they know overseas to personally serve the member and file an affidavit of service. Otherwise, it may be necessary to serve under that country’s rules of service of process or, if one exists, the applicable treaty between the United States and the country. This could be a Status of Forces Agreement or some other type of agreement.

Additionally, the Colorado Supreme Court has ruled that a service member who resides in Colorado only due to military orders is not a legal resident.18 A service member must take some affirmative step to assert domicile in Colorado, which means a minimum of a 91-day physical presence and additional actions showing an intent to remain or return.19 These actions could be, for example, changing a state of residence in military records, registering to vote, purchasing property, or procuring a Colorado driver’s license. The same provisions are true for military spouses whose states of residence do not automatically change solely because they relocated with their spouses under military orders.

Part 3: International Humanitarian Law,

by Michael McKenna

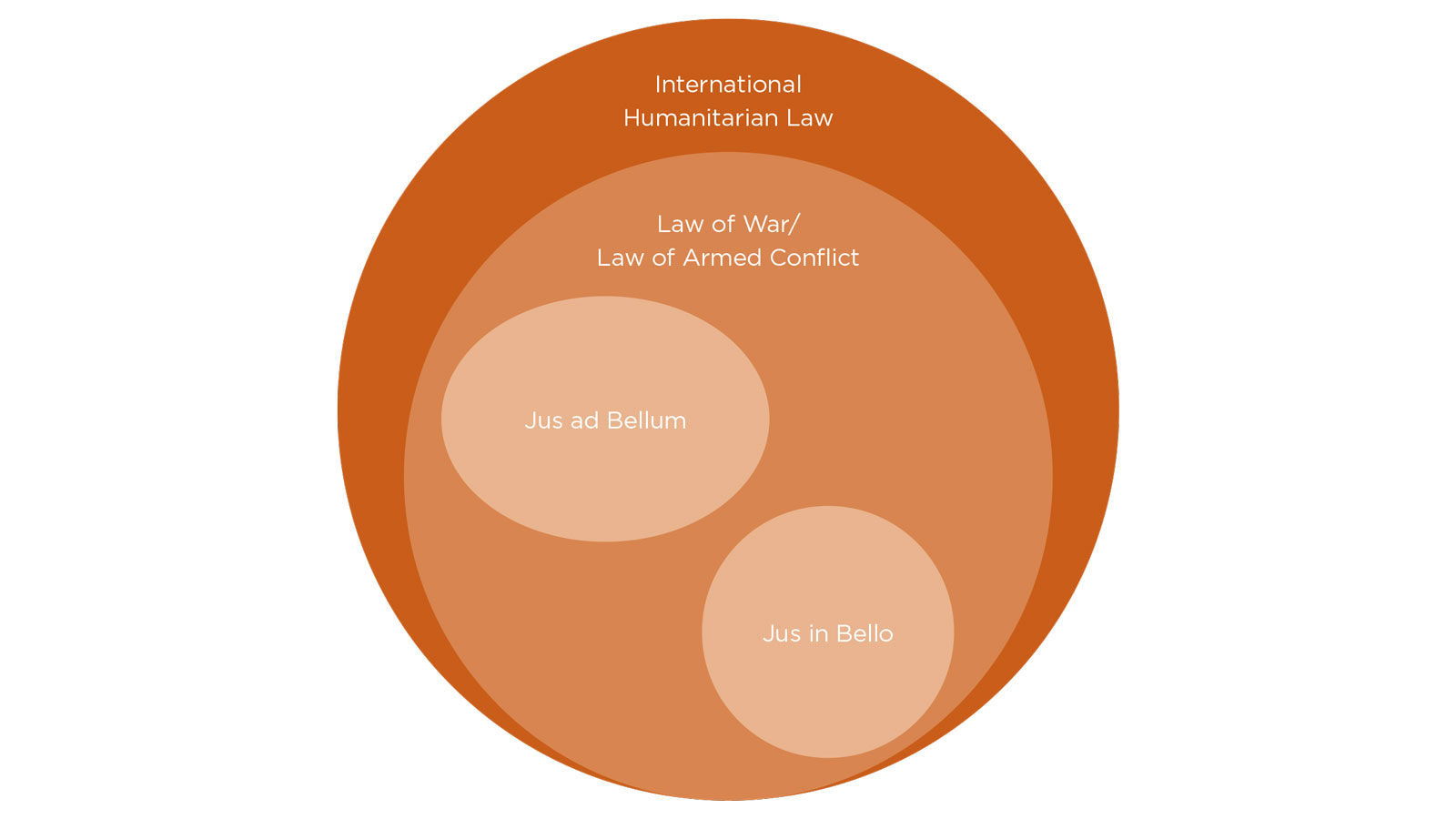

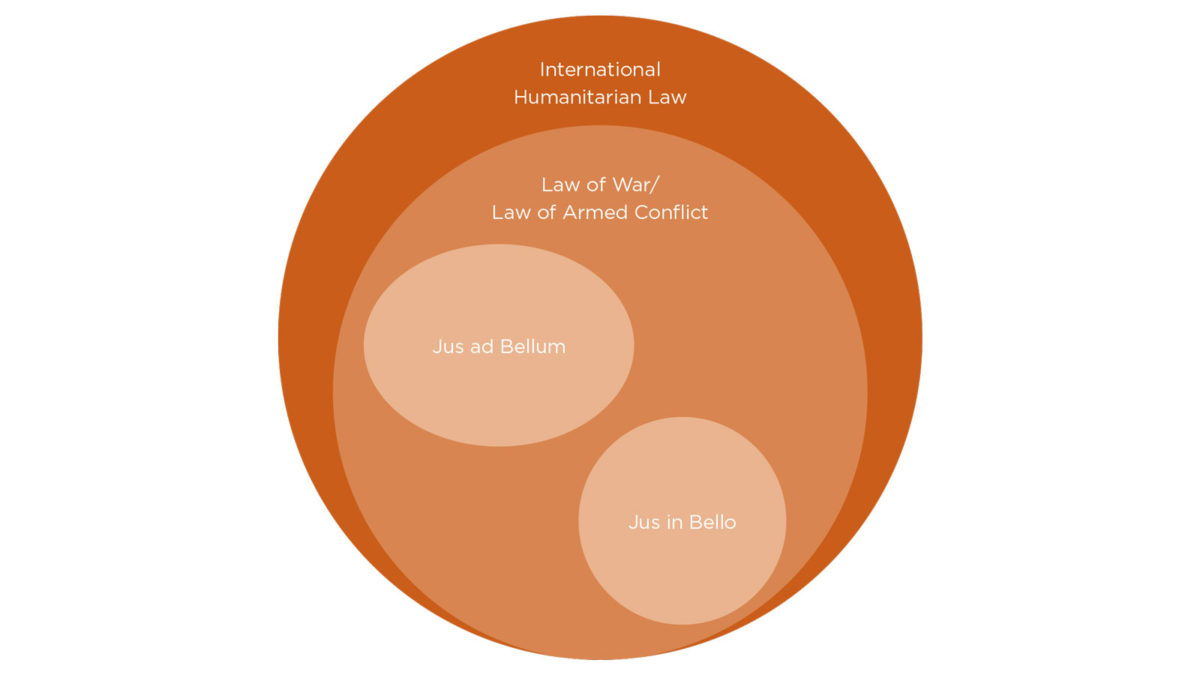

One key facet of difficult issues faced by service members is the application of legal standards in international armed conflicts. International humanitarian law (IHL) is a set of rules that seek, for humanitarian reasons, to limit the effects of armed conflict. IHL protects people who are not, or who are no longer, participating in hostilities and restricts the means and methods of warfare. IHL encompasses the law of war (LOW) (also referred to as the law of armed conflict, or LOAC) as well as international law regulating the effects of war (e.g., refugees)20. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has defined IHL to mean international rules, established by treaty or custom, that specifically intend to solve humanitarian problems arising directly from international and non-international armed conflicts. For humanitarian reasons, these rules protect people and property that are, or may be, affected by conflict by limiting the parties’ choices of the means and methods of warfare.21

One key facet of difficult issues faced by service members is the application of legal standards in international armed conflicts. International humanitarian law (IHL) is a set of rules that seek, for humanitarian reasons, to limit the effects of armed conflict. IHL protects people who are not, or who are no longer, participating in hostilities and restricts the means and methods of warfare. IHL encompasses the law of war (LOW) (also referred to as the law of armed conflict, or LOAC) as well as international law regulating the effects of war (e.g., refugees)20. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has defined IHL to mean international rules, established by treaty or custom, that specifically intend to solve humanitarian problems arising directly from international and non-international armed conflicts. For humanitarian reasons, these rules protect people and property that are, or may be, affected by conflict by limiting the parties’ choices of the means and methods of warfare.21

The LOW is defined as the part of international law that regulates the conduct of armed hostilities. It is US Department of Defense (DoD) policy that US LOW obligations are national obligations binding upon every soldier, sailor, airman, and marine.22The fundamental purposes of LOW are both humanitarian and functional in nature. The humanitarian purposes include protecting non-combatants and combatants from unnecessary suffering, safeguarding those who fall into the hands of the enemy, and facilitating the restoration of peace. The functional purposes of LOW for the armed forces include ensuring good order and discipline, fighting in a disciplined manner consistent with national values, and maintaining domestic and international public support.23

IHL can be subdivided into two substantive areas: jus ad bellum and jus in bello. Jus ad bellum regulates the resort to armed force founded on just war principles such as justified self-defense. Jus in bello defines the rules applicable in the conduct of war with standards of proportionality and distinction between combatants and noncombatants such as civilians. Jus ad bellum therefore regulates the “why” of warfare, while jus in bello regulates the “how” of warfare.24

Governments and armies of the past relied more heavily on internal codes to ensure their soldiers remained disciplined. One example is the Lieber Code issued by President Lincoln in 1863 during the Civil War. Because most troops of that period were inexperienced conscripts, there was a need for a strong code of discipline and a code to regulate interactions with civilians. In addition, the governance of the newly occupied southern states proved problematic for commanders untrained in civil-military affairs. The Code addressed these concerns by (1) restricting participation in combat to those subject to the commander’s control and discipline, (2) defining permitted conduct in warfare, and (3) providing authority and guidance for the effective governance of newly captured territory. From the perspective of the executive branch, the Lieber Code had one significant additional benefit: because it was a military code based on the authority of international law, it restrained Congress from undesired interventions in military operations.25

As long as wars have existed, there have been efforts to contain the methods of warfare and mitigate the horrors involved in legally binding norms such as the Lieber Code. Today the main legal sources of IHL can be found in international treaty law, most prominently in the Four Geneva Conventions of 1949, their Additional Protocols, and international customary law (ICL). State actors are bound by their ratification of treaties and are under an international legal obligation to abide by them. According to the ICRC, customary international law is made up of rules that come from a general practice accepted as law. To accept a practice as customary, the practice must have widespread acceptance as a matter of law among nation-states. Examples of ICL as set forth by the ICRC include specific prohibitions regarding indiscriminate attacks, requirements of target verification, prohibitions on certain means and methods of warfare, prohibitions on deprivations of liberty, and fair trial guarantees.26 A comprehensive set of examples is found in the 2005 ICRC Database.27 While the United States recognizes many of these ICL principles, they are not all explicit US policy.

Much like the US Constitution is based on natural law principles, IHL is broadly based on basic humanitarian principles. The principles are not law per se or a codification, but an understanding of these principles guides our analysis of law of war issues.

Principle of Military Necessity

The principle of military necessity is set forth by reference in the Hague Convention, which forbids a belligerent from destroying or seizing enemy property “unless such destruction or seizure be imperatively demanded by the necessities of war.” The principle of military necessity does not, however, authorize the intentional targeting of places or people protected under international law, such as prisoners of war (POWs). US policy emphasizes the principle as one that authorizes the use of force required to accomplish the mission but does not authorize acts prohibited under the LOW.28 US policy clearly states that the doctrine of military necessity does not provide a defense to otherwise criminal or military charges.29 Famously, Nazi officials set forth military necessity as a defense to numerous horrific charges in the Nuremberg tribunals; that defense was ruled to be insufficient generally as a matter of law.30

The tragic experiences of World War II propelled demands that the Axis powers be tried under international law. After much internal debate, the Allies signed the London Agreement on August 8, 1945, which established an International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg for the trial and punishment of war criminals of the European Axis. Seeking to avoid the failure of post-World War I war crimes prosecution failures, the Allies, in particular the United States, devoted substantial resources to Nuremberg. Chief Justice Jackson of the US Supreme Court served as the lead prosecutor. The Tribunal convicted 19 of the 22 major offenders.31 The entire Nuremberg records are on permanent file in the Netherlands at the International Court of Justice for future generations to contemplate32.

Nuremberg, for all its critics, has had a lasting legacy in IHL. The Nuremberg trials and the charter that authorized them were a turning point in the history of international law and marked a transition that “roughly corresponds to that in the evolution of local law when men ceased to punish local crime by ‘hue and cry’ and began to let reason and inquiry govern punishment.”33 The Nuremberg Charter identified three types of crimes: (1) crimes against peace, (2) war crimes, and (3) crimes against humanity. At the time of the Nuremberg trials, however, only the laws and customs of war were firmly established in international law; crimes against peace and crimes against humanity were novel concepts. Since 1945, IHL has codified the concept of war crimes and crimes against humanity, making individual criminal responsibility one of the most significant legacies of the Nuremberg trials and providing a legal precedent for the International War Crimes Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda.

Principle of Distinction

The foundations for findings of criminality in warfare, such as Nuremberg, rest on a set of basic principles that primarily protect noncombatants. Sometimes referred to as the principle of discrimination, the principle of distinction requires that combatants be distinguished from civilians and that military objectives be distinguished from protected persons and places. This principle requires that combatant parties direct their military operations against other combatants and military objectives. Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions gives the following example. The principle of distinction might prohibit area bombing in certain populous areas, or bombardment, which treats as a single military objective a number of clearly separated and distinct military objectives in a city, town, or village. This provision, as a discussion point, would certainly call into question the practice of massive area bombing of cities by all combatants during World War II.34

Principle of Proportionality

According to the principle of proportionality, the anticipated loss of life and damage to property incidental to military attacks must not be excessive in relation to the anticipated concrete and direct military advantage. Incidental damage and casualties are therefore permissible in military operations. Incidental damage consists of unavoidable and intentional civilian deaths and property destruction incurred while attacking a proper military target. Incidental damage is not a violation of the LOW.35

An example of this principle was the August 2022 drone strike that killed Ayman al-Zawahiri in Kabul Afghanistan. According to DoD, Zawahiri was killed in an over-the-horizon operation in Kabul, where he was residing as a guest of the Taliban. The house was struck by two Hellfire missiles in a precision counterterrorism operation. Zawahiri was the target and the only casualty. “We are confident through our intelligence sources and methods—including multiple streams of intelligence—that we killed Zawahiri and no other individuals,” a senior administration official said.36

Also highlighting the renewed importance of this principle to US policy, DoD released its Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response Action Plan on August 25, 2022, which details nearly a dozen objectives creating institutions and processes to reduce the likelihood of civilian casualties. In a memo accompanying the release of the action plan, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin III called its objectives “ambitious but necessary,” and press secretary Brig. Gen. Patrick S. Ryder told reporters that the plan will “enable DoD to move forward on this important initiative.” Austin ordered an action plan shortly after theNew York Timesreported that airstrikes caused hundreds of civilian casualties in the Middle East. Those reports followed the high-profile death of 10 civilians in Kabul in August of 2021 caused by an erroneous airstrike during the US withdrawal.37 Among the action plan’s objectives is the establishment of a civilian protection center of excellence; the incorporation of guidance for addressing civilian environmental and civilian harm mitigation capabilities and processes throughout the joint targeting process; and the creation of a steering committee to oversee the action plan’s implementation.38

Principle of Unnecessary Suffering

This principle is sometimes referred to as humanity or superfluous injury. It requires military forces to avoid unnecessary suffering. The use of arms, projectiles, or material calculated to cause unnecessary suffering is prohibited. This principle applies to the legality of weapons and ammunitions themselves and to how such weapons and ammunition are used. Military personnel may not use arms that are designed to cause unnecessary suffering (e.g., projectiles filled with glass, hollow point or soft point small caliber ammunition, or lances with barbed heads) or use otherwise lawful weapons in a manner calculated to cause unnecessary suffering.39

Dissemination and Education of IHL: The American Red Cross, the ICRC, and Military Advisers

Respecting IHL and ensuring compliance with its tenets is at the core of the Geneva Conventions and its Additional Protocols. Member states of the Geneva Conventions, including the United States, are mandated to disseminate the text of the Conventions in times of peace and war as widely as possible, in particular in military programs, and to adopt necessary legislation to effectively suppress violations of IHL. Also providing IHL dissemination, the American Red Cross (ARC) provides IHL dissemination and IHL education under the authority of the Geneva Conventions and as an auxiliary of the US government under the 1905 ARC Charter.40 The Statutes of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement require those entities to disseminate IHL education programs and help their respective governments to do so. The ARC received a grant from the US Institute of Peace in 1988 for its IHL dissemination program, which enabled the development of IHL education materials for the general public. IHL training and internal grant programs starting in 1993 enable this ongoing mission of the ARC.41

A critical part of the Red Cross IHL training program is the IHL Youth Action Campaign (YAC), which operates like youth 4-H and scouting programs. The program empowers young people ages 13 to 24 to learn about IHL. Young people volunteer to become advocates and provide education about IHL to themselves and the public by exploring topics with their communities through peer-to-peer education campaigns. Youth teams participate in IHL training using social media and in-person events to promote knowledge and awareness. The 2023 theme of the IHL YAC program is environmental protections during conflicts, such as the need to preserve natural and manmade resources. IHL YAC provides its participants with outstanding leadership, managerial, and organizational opportunities. The best teams are given an opportunity to attend the annual YAC of the Red Cross Summit in Washington, DC.42

Though many people think of it as one entity, the Red Cross movement actually includes three major organizations: the national Red Cross, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, and the ICRC. Founded on the humanitarian principles of the relief of suffering and neutrality, the movement’s mission statement is to “prevent and alleviate human suffering wherever it may be found to protect the life and health and to ensure respect for the human being, in particular in times of armed conflict and other emergencies, to work for the prevention of disease and the promotion of health and social welfare. . . .”43

The ICRC has a leadership role in the movement, directing and coordinating the emergency relief efforts of the societies. It is the only organization authorized by the Geneva Conventions to visit POWs. The ICRC also provides emergency food, water, and medical help; searches for missing people; and promotes, monitors, and develops IHL. The ICRC is governed solely by an assembly of Swiss nationals.44

The US government is the ICRC’s largest single donor. In 2004, the United States funded 20% of its 2004 budget of $650 million (for a total of $130 million).45 Founded in 1863, the ICRC is a private nongovernmental organization (NGO) of Swiss citizens that has played a seminal role in the development and implementation of the LOW relating to the protection of war victims. During World War II, the ICRC supplemented the efforts of the protecting powers and undertook prodigious efforts on behalf of displaced persons and POWs. These efforts included establishing a Central Prisoner of War Agency with 40 million index cards, conducting 11,000 visits to POW camps, and distributing 450,000 tons of relief items.46 The ICRC’s role as an impartial humanitarian NGO is formally recognized by the Geneva Conventions. The role of ICRC with the consent of the combatant parties has been to step into the breach, conducting inspections of detainees and POWs (e.g., in Desert Storm, in operations in Iraq, in Afghanistan, and worldwide). When armed conflict is non-international or internal in nature, Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions recognizes the prerogative of the ICRC and other impartial humanitarian organizations to provide services such as inspections of facilities, the restoration of families, refugee services, and logistical assistance.47

The ICRC’s activities are based on the Geneva Conventions and the Statutes of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. Its mandate is to protect and assist victims of armed conflicts and internal disturbances. First, the ICRC protects and assists the victims in the field: it protects the civilian population; visits POWs and other detained persons; provides food, medical, and other assistance; reestablishes the link between separated family members through Red Cross Messages; tries to find people who went missing during the conflict; and reunites family members. Second, the ICRC is mandated by the international community to act as promoter and guardian of IHL. Its delegates in the field, which number about 1,000, monitor respect of IHL and, in the case of violations, intervene with the party concerned.48

The ICRC seeks to establish a constructive dialogue with governmental authorities as well as with armed opposition groups, all of which are bound by humanitarian law. The ICRC strives to preserve trust with all parties involved by maintaining confidentiality and discretion during discussions. The principle of confidentiality is thus not an end in itself, but rather a working methodology throughout its mission activities. The principle has its limits: when severe violations of humanitarian law continue even after the ICRC has intervened, it reserves the right to publicly denounce such violations.49

The ICRC, a major player in academic IHL, has led several recent efforts to clarify and develop IHL. It is commonly referred to as the “guardian of international humanitarian law.” Reflecting its mandate “to work for the understanding and dissemination of knowledge of international humanitarian law applicable in armed conflicts and to prepare any development thereof,” the ICRC has recently published numerous treatises. In 1995, the ICRC commissioned its Legal Division to conduct a large-scale comprehensive study to codify “customary rules of IHL applicable in international and non-international armed conflicts.” Carried out over a span of 10 years in consultation with over 150 legal experts, the resulting Customary International Humanitarian Law study includes over 3,000 pages in three volumes of work seminal in the field, much like familiar “black letter law” in the United States.50

IHL Dissemination in the Military

In addition to general requirements, Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions also requires states to ensure that legal advisers are available when necessary to advise military commanders at the appropriate level on the application of the Geneva Conventions and their Protocols and on the appropriate instruction to give to the armed forces. Moreover, military commanders are to ensure that armed forces under their command are aware of their IHL obligations. Commanders are to prevent their subordinates from committing IHL violations and to institute necessary disciplinary or penal actions, whichever is appropriate, against any violator. Through dissemination, training, presence of legal advisers, and underscoring responsibility on commanders, the Geneva Conventions and their Protocols have thus placed understanding of the law at the center of IHL. In so doing, the Geneva Conventions drafters aimed to generate the reflex among properly trained combatants to integrate IHL as part of their strategy and modalities of warfare. Before launching an attack or as they do so, choosing means and methods compliant with the LOW should be an integral part of the thinking and action.51

Since the Gulf War in 1991, the presence of legal advisers embedded in front units and involved in operational decisions has become routine in the US, British, NATO, and Israeli armed forces. In the US armed forces, uniformed JAG officers and the JAG Corps fulfill this role.52 JAG officers have served as legal advisers on LOW issues down to the brigade level in US forces operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.53 Legal operational advice is the most important internal monitoring device available to the government and the army’s high command in controlling the behavior of the armed forces. Operational legal advisers are required not only to approve activities but also to inculcate the relevant legal norms and incorporate international law into military practice. Observing the emergence of legal operational advice in the Israel Defense Forces, one author concluded that “[t]he presence of operational legal advisers has enabled the military to ‘internalize’ IHL, with all that the term implies with respect to the assimilation of that body of law into the modus operandi of the armed forces themselves.” Thanks to them, “IHL has been transformed from an ‘external’ constraint on military action to an intrinsic facet of the military’s own operational code.”54

Helmuth von Moltke, chief of staff of the Prussian Army, emphasized that legal restraints, as well as “religious and moral education,” are the key to ensuring that “the gradual progress in morality [is] reflected in the waging of war.”55 That gradual progress is the underlying lynchpin of the IHL system.

Conclusion

This three-part article discussed the role of judge advocates, looked at some of the unique legal needs of active duty service members and veterans with regard to family law, and provided an overview of international humanitarian law. Given the breadth of issues that can arise for our service members and veterans, Colorado attorneys practicing in all areas have something to offer this community. Whether you’re a current or former military member, a family member, or have an interest in the military community, there is a place for you in our section and clinics. For more information, please reach out to Ashley Staab, CBA section liaison, at (303) 860-1115 or astaab@cobar.org, or Sabra Janko, section chair, at (719) 445-0536 or sabra@jankolaw.com. A little help goes a long way.

Related Topics

Notes

1. 10 USC § 1044. See also OpJAGAF 2014/19 (Sep. 22, 2014).

2. Providing Legal Servs. by Members of the JAG Corps, Hearing Before the Subcomm. on Personnel of the Sen. Armed Servs. Comm., 112 Cong. 217 (2011) (statement by Lt. Gen. Chipman, JAGC, US); US Court of Military Appeals, Annual Report of the Code Committee on Military Justice (Oct. 1, 1985).

3. See 50 USC §§ 3901 to 4043.

4. 50 USC §§ 3955 to 3956.

5. H.R. Rep. No. 103-200 at 286 (1993).

6. 10 USC § 1044(a)(1)–(2).

7. During the author’s time as a legal assistance attorney stationed at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, he helped service members recover tens of thousands of dollars in wrongfully withheld security deposits and rent prepayments.

8. Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue Service, Publication 525 (Jan. 25, 2022).

9. Colorado Dep’t of Revenue, Military Servicemembers Guide at 5 (June 2021).

10. In re Parental Responsibilities Concerning M.E.R.L., 490 P.3d 1010, 1017 (Colo.App 2020).

11. Mansell v. Mansell, 109 S. Ct. 2023, 2032 (1989); In re Parental Responsibilities Concerning M.E.R.L., 490 P.3d at 1017.

12. Defense Finance Accounting Service, https://www.dfas.mil/RetiredMilitary/disability/VA-Waiver-and-Retired-Pay-CRDP-CRSC.

13. In re Tozer, 410 P.3d 835 (Colo.App. 2017).

14. See, e.g., Headquarters Dep’t of the Army, Army Reg. 20-1, Inspector General Activities and Procedures (Mar. 23, 2020).

15. See, e.g., Headquarters Dep’t of the Army, Army Reg. 608-99, Family Support, Child Custody, and Parentage (Nov. 13, 2020).

16. Id.

17. 32 CFR § 516.10 (d)(1)–(2), Service of Civil Process Within the United States (Sep. 6, 1994).

18. Viernes v. District Court, 509 P.2d 306 (Colo. 1973).

19. In re Marriage of Akins, 932 P.2d 863, 867 (Colo.App. 1997).

20. American Red Cross, “Summary of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and Their Additional Protocols” (Apr. 2011), https://www.redcross.org/content/dam/redcross/atg/PDF_s/International_Services/International_Humanitarian_Law/IHL_SummaryGenevaConv.pdf.

21. Bouvier, “International Humanitarian Law and the Law of Armed Conflict,” Peace Operations Training Institute at 12 (2020).

22. Bill and Marsh, eds., “Operational Law Handbook,” Int’l and Operational Law Dep’t, Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School, US Army at 32 (2010) (hereinafter, Operational Law Handbook).

23. Id.

24. Bouvier, supra note 21 at 23.

25. Benvenistic and Cohen, “War is governance: Explaining the logic of the laws of war from principal-agent perspective,” 112 Mich. L. Rev. 1363, 1388–89. (June 2014).

26. Gillich, “Illegally Evading Attribution: Russia’s Use of Unmarked Troops in Crimea and International Humanitarian Law,” 48 Vanderbilt J. Transnat’l L. 1191, 1199–1201 (2015).

27. https://ihl-databases.icrc.org (originally published by Cambridge Univ. Press, 2005).

28. Operational Law Handbook, supra note 22 at 10.

29. Id. at 11.

30. Baltes, “Prosecutor v. Tadic: Legitimizing the Establishment of the International Crimes Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia,” 49 Me. L. Rev. 577, 588 (1997).

31. Id. at 589.

32. Nuremberg Trial Archives, https://www.icj-cij.org, Internat’l Court of Justice, The Hague. See generally The Nuremberg Trial 1946, 6 FRD 69 (1946, 1947), for a comprehensive documentation of the trials.

33. Baltes, supra note 30 at 589.

34. Operational Law Handbook, supra note 22 at 11.

35. Id.

36. US Dep’t of Defense, Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response Action Plan Fact Sheet, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3140007/civilian-harm-mitigation-and-response-action-plan-fact-sheet (Aug. 25, 2022).

37. Hadley, “Pentagon’s Plan to Reduce Civilian Harm May Not Work in Future Conflicts, Experts Say,” Air Force Magazine (2022), https://www.airforcemag.com/pentagons-plan-to-reduce-civilian-harm-may-not-work-in-future-conflicts-experts-say.

38. https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3140007/civilian-harm-mitigation-and-response-action-plan-fact-sheet.

39. Operational Law Handbook, supra note 22 at 12–13.

40. Brown, “The American Red Cross and International Humanitarian Law Dissemination,” published in “The Law of War in the 21st Century: Weaponry and Use of Force,” US Naval War College 115, 117 (2006).

41. Id. at 117.

42. https://www.usarmyjrotc.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/2022-2023-IHL-YAC-Brochure-JROTC-English.pdf.

43. See “Know Your Red Crosses: Is the ICRC disservicing America?,” Charity Watch, https://www.charitywatch.org (2006). While acknowledging the humanitarian roles of the ARC and the ICRC, Charity Watch has been highly critical of both organizations.

44. Id.

45. Id. Charity Watch has asserted that the ICRC has vilified various US actions as contrary to IHL, such as the use of land mines and tear gas, despite the US being the ICRC’s largest monetary donor. The ICRC asserts that it remains neutral; its positions are not without controversy.

46. Operational Law Handbook, supra note 22 at 33.

47. Id.

48. Lavoyer, “International Humanitarian After Bosnia,” Int’l Law Student Ass’n, 3 ILSA Comp. L. 583, 585 (1997).

49. Id.

50. Schmitt and Watts, “The Decline of International Humanitarian Law Opinio Juris and the Law of Cyber Warfare,” 50 Tex. Int’l L.J. 189, 191 (2015).

51. Williamson, “The Knight’s Code Not His Lance,” 43 Case W. Res. J. Int’l L. 447, 452 (2010).

52. Dep’t of Defense, Chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Publication 3-84, “Legal Support” (Aug. 2, 2016), https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/jp3_84.pdf.

53. See Dickinson, “Military Lawyers on the Battlefield: An Empirical Account of International Law Compliance,” 104 Am. J. Int’l L. 1, 16 (2010). Professor Dickinson’s article is supportive of both uniformed JAG officers and the Operational Law Handbook, supra note 22, while being highly critical of the Bush Administration.

54. Benvenistic and Cohen, supra note 25 at 1412.

55. Id. at 1414.