What Took So Long?

April 2021

Download This Article (.pdf)

History is full of anomalies in the form of time delays. As we all know, over four score and seven years passed between the founding of our country until persons of color, as US citizens, gained the right to vote (15th Amendment to the Constitution, ratified February 3, 1870). Women finally achieved the same status (19th Amendment, ratified August 18, 1920) 50 years later. In hindsight, of course, one wonders what took so long.

Worth their Wait

Similarly, technology has its share of time delay anomalies. The time between the invention of the wooden pencil by an Italian couple, Simonio and Lyndiana Bernacotti (1560), and the pencil eraser assembled as part of a pencil (Hymen Lipman US Patent No. 19,783, March 30, 1858) was about 300 years. In other words, someone finally thought of a convenient way to erase pencil marks made by wooden pencils that had been used for three centuries. The US Supreme Court later invalidated the US patent, as it turned out, stating that the patented article was only an aggregation of separate elements (Reckendorfer v. Faber, 92 US 347 (1875)).

To replace glass containers, the metal can—actually made of iron lined with tin—was invented in 1810 by Peter Durand to store food. How long do you think it took for the can opener to be invented after metal cans were introduced?

a) 1 year

b) 5 years

c) 10 years

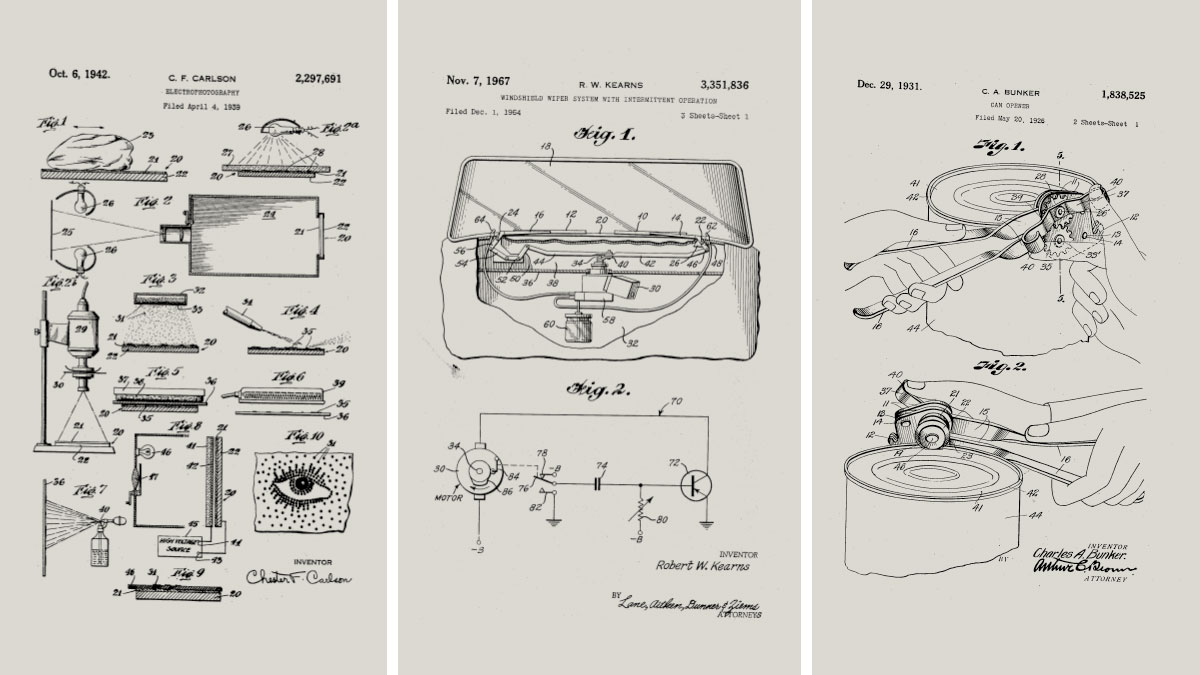

The answer is an astounding 48 years. Ezra Warner patented the first can opener on January 5, 1858 (US Patent No. 19,063), almost 50 years after metal cans appeared. Warner designed a tool with a cutting blade and a guard that prevented the blade from penetrating too far into the contents of a can. The guard could swing out of the way so a second curved blade could cut around the top of the can with a saw-like action. But after the top of the can was removed, the upper portion of the can had a jagged edge. It wasn’t until December 29, 1931, that Charles Arthur Bunker received US Patent No. 1,838,525, which described the first modern can opener most of us now use.

Slow and Steady

Sometimes inventions are solutions looking for a problem. Consider the photocopier. Chester Carlson, a patent attorney as it turned out, worked in his mother-in-law’s kitchen developing the first photocopier and obtaining US Patent No. 2,297,691 but found that no one was especially interested in his invention. He approached 20 large corporations and the US Navy, which could not be convinced any office or anyone would want to purchase a machine that made copies.

“We have carbon paper,” the executives of IBM, RCA, G.E., and Eastman Kodak said. “Why would anyone need a copier?”

“No,” Carlson replied. “This machine is for more than two or three copies.”

“We have a local printer when we need 5,000 brochures.”

“This machine is for making 5 or 10 or 50 copies.”

“Ridiculous,” they said. “There’s simply no market for that.”

Eventually, Carlson attracted the small Haloid Company, founded in 1906 (coincidentally, the year Carlson was born), a company with $30,000 in annual sales of photographic paper. Haloid decided to take a chance on his invention. It became the Xerox Corporation, which sold its first photocopier only 34 years after Carlson started his project. Xerox made Carlson a multimillionaire, as he was paid one-sixteenth of a cent for every Xerox copy made worldwide. Xerox became one of the 100 largest companies in America, with tens of billions of dollars in sales annually.

Robert Kearns, Ph.D., the inventor of the intermittent windshield wiper, had difficulty convincing Ford Motor Company executives that drivers would want or need a delay mechanism to swipe water from a windshield. When Ford was finally convinced to incorporate intermittent windshield wipers in automobiles and trucks, Kearns had to bring a patent infringement lawsuit against the company. After a 12-year legal battle during which Kearns suffered a nervous breakdown and a divorce, the Ford Motor Company agreed to settle with him for $10.2 million, and in 1992, Kearns won a judgment against Chrysler for $18.7 million. Today, some 150 million automobiles are equipped with intermittent windshield wipers. The 2008 Universal Pictures movie Flash of Genius was based on Kearns’s story.

The Speed of Light

The time it takes for an invention to be accepted by the general population is fascinating. In 1876, when Alexander Graham Bell received his telephone patent, considered to be the most valuable patent of all time, obviously only one or two telephones existed. Seventeen years later, in 1893, only 3.2 million phones were in use by the United States’ 63 million people. But by 1918, our country had grown to 103 million and the number of telephones had tripled to about 10 million. In other words, it took 42 years for the telephone to reach only 10% of the population.

Electrification of American households and Thomas Edison’s electric lightbulb are other examples. Although electricity distribution began in 1882, by 1925, some 43 years later, only half of American homes had electricity. Edison’s incandescent lightbulb was demonstrated on New Year’s Eve, 1879. It wasn’t until four decades later, in the 1920s, that most new homes in America were wired for electric light instead of gas fixtures. That single invention transformed rural America into an urban country.

Picking up the Pace

The time from introduction of technology to consumer use continues to decrease. On April 3, 1973, a Motorola researcher and executive made the first mobile telephone call from handheld subscriber equipment, placing a call to a Bell Labs executive, Bell Labs being Motorola’s rival. That mobile phone weighed about two-and-a-half pounds and took 10 hours to recharge. Today, 94% of Americans own cell phones.

In 1968, Hewlett-Packard Company referred to a new product as a personal computer, but the advertisement was deemed too extreme for the target audience. So the company replaced the name with “programmable calculator.” Mass-market consumer electronic devices with microcomputers were introduced in 1977. Three machines—the Apple II, PET 2001, and TRS-80—were also released in 1977, becoming the most popular such devices by late 1978. IBM introduced its IBM PC in August 1981, leading Time magazine to name the home computer the Person of the Year for 1982, the first time the magazine gave its award to an inanimate object. More than one billion personal computers have been sold worldwide since the mid-1970s.

The accelerating time for acceptance of new technology is a function of communication and peer pressure. With TV and internet advertisements, the next big thing can be in the hands or on the feet or in the belly of consumers days or weeks—not years—after it is introduced to the public.

Just as technology has accelerated the development and acceptance of new products, in politics—especially voting issues—the world has also sped up. No longer do the results of elections take weeks or months to reach us. Oops, bad example.