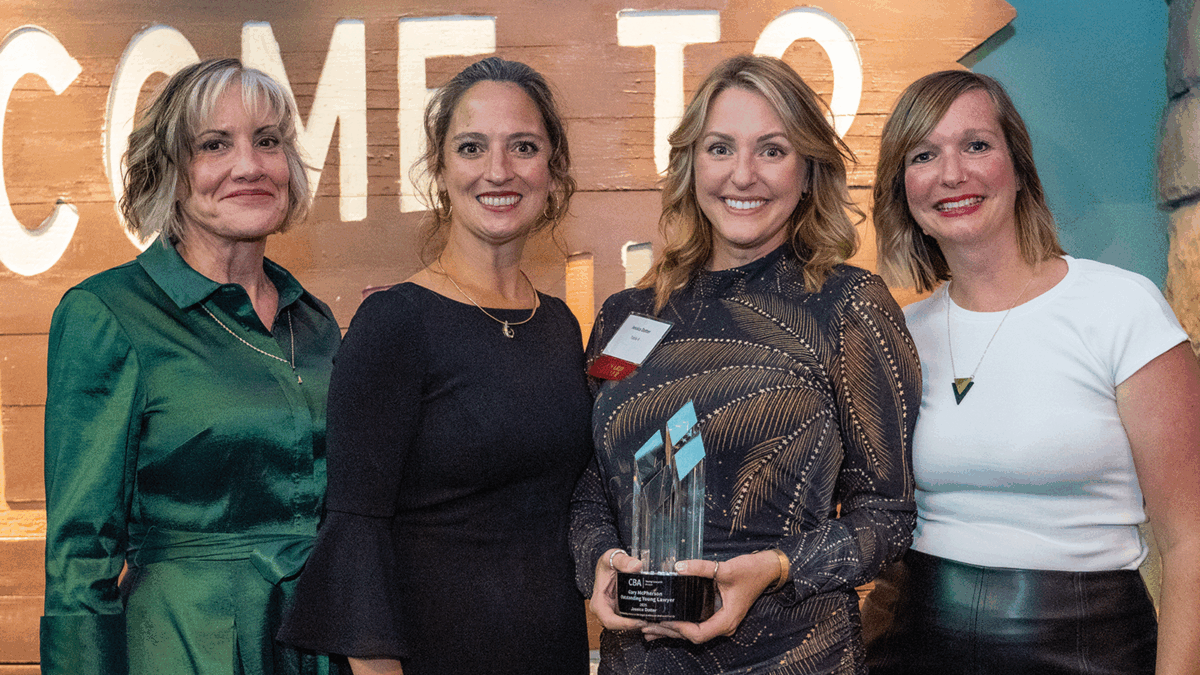

When Purpose Meets Profession

Outstanding Young Lawyer Jessica Dotter Reflects on Her Career as a Prosecutor

January/February 2026

Download This Article (.pdf)

Jessica Dotter, this year’s Outstanding Young Lawyer of the Year, is an impressive example of when purpose and career coincide. Her calling to serve—and to seek justice for vulnerable victims—took root early and has guided her career ever since.

Early Influences

Dotter remembers being greatly affected by what she learned in her history courses. “I was fascinated by learning about things such as slavery and the Holocaust,” she says. “Naturally, I had emotional responses to learning about terrible things that humans do to one another, but I was equally as inspired by the battles taken on to eradicate slavery and to stop Nazi Germany.”

Her inspiration deepened as she learned about civil rights and legal icons. “I learned about heroes like Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and I was in awe of how they dedicated their lives to activism in multiple facets to make society a better place. Pursuing a career in which I could hold people accountable if they harmed others just made sense.”

Dotter’s sense of purpose was further shaped by one of her mom’s favorite shows, Law & Order: Special Victims Unit. “I’d often sneak into her room or onto the couch to watch it with her. I remember seeing the female prosecutor and idolizing her—I was so inspired by this strong, intelligent woman who stood up for sexual abuse victims no matter the defendant.” Her parents, amused by her strong opinions and logical arguments from a young age, joked that a legal career seemed inevitable.

Another formative moment came in middle school when she learned about the injustices faced by Carl Brashear, a Navy diver who overcame both overt racism and the loss of a leg before becoming a master diver. “I was disgusted by the challenges he faced due to racists trying to belittle him and force him to quit. His story inspired me to battle onward for the right outcome no matter the opposition. The protection of our civil rights and freedoms became a core concern of mine—and I’m proud that as a prosecutor, I’ve had an ability to ensure that protection in criminal cases.”

Law School Years

Dotter recalls law school fondly, calling herself “one of the few lawyers who absolutely adored law school.” While she would not consider law school easy, she found the work extremely fulfilling. “I wish that I had put the same amount of work into my undergraduate degree, because the joy that I received from growing and learning the law really cannot be put into words. My brain thrived by analyzing case law and debating policy and rules. I knew I wanted to be a courtroom attorney in criminal law—although criminal law was one of my lower grades,” she adds with a laugh.

Dotter studied at the Washburn School of law in Topeka, Kansas, having relocated to the state by the time she was in high school. Her parents were in the US Air Force and previously had been stationed in California and Colorado Springs for a time. When law school ended, she knew where she wanted to go next. “I loved the Midwest, but by the time I had graduated law school, I was ready to move farther west.” Taking the Colorado bar was an easy choice: “I wanted to be near family who had settled here and loved camping and hiking—which was lacking in Kansas.”

Prosecution Career

Today, Dotter serves as senior chief for legislative policy and special victims prosecution at the Colorado District Attorneys’ Council—a role she acknowledges isn’t for everyone. “I’ve never been able to quite describe it to others, but I have an ability to abhor an offender’s behavior yet still take a clinical approach to the work to fulfill my duties as an independent law enforcement officer and only pursue just prosecutions.”

She notes that the emotional toll of this type of work is real, and that prosecutors often need to devise ways to cope with it. “I certainly experience secondary trauma and have made it a priority to train all prosecutors on the need to incorporate resilience practices into our work.”

Another central tension of her work lies in the prosecutor–survivor relationship: “Technically they aren’t our clients because we work for the people of the state of Colorado, not on behalf of any individual—they don’t pursue criminal action, the way a person would sue another person. The government, via us as prosecutors, pursues it on the behalf of all people.”

To manage this tension, she strives for transparency. “I feel one of the most important things I can do for them is to manage their expectations upfront—the criminal justice system wasn’t created to heal victims of crime or for them to get vengeance against someone who has harmed them; it was created so that when anyone is accused of a crime, the government, which has been given the authority to take away their liberty by imprisoning them or criminalizing them, must do so with due process, transparency, and fairness. That’s an incredibly difficult truth for sexual assault survivors, who are sitting across a desk from me not because they chose to be, but because someone harmed them in one of the most damaging forms possible, but it’s a truth that they are owed by prosecutors.”

This truth can be painful for survivors to hear, but Dotter still wants them to feel empowered throughout the process. “I do everything I can to provide them control over the process to ensure that their voice is heard, even if it’s in disagreement with mine, which is a great privilege that prosecutors who work in special victims units enjoy. I am proud of how far the criminal justice system has come in regard to understanding the trauma of sexual abuse, but there is definitely room for us to be greater educators in the community and for law-enforcement to dispel damaging myths about sexual abuse and eradicate victim blaming.”

Service Beyond the Courtroom

Dotter’s commitment to supporting survivors extends well past office hours. She volunteers with local and statewide victim advocacy groups, aware that most survivors never report their abuse to law enforcement. “It is vital that these confidential victim advocacy organizations exist to provide housing, resources, and therapy to survivors.”

Much of her volunteerism centers on training victim advocates and forensic interviewers (who specialize in interviewing children), as well as attending fundraisers for the organizations. She served for six years on the board of directors for Blue Sky Bridge, a child advocacy center that provides forensic interviews, education, and therapy to support children and families in Boulder County. Most recently, she has been attending fundraisers for the Blue Bench, an adult sexual assault advocacy organization in Denver.

In becoming the kind of steadfast and confident advocate she is, Dotter recalls some good advice she received from her co-counsel early on in her career: “I need you to speak up when you have an opinion. You need to trust and remember that you belong in this role and the only way you can fail is to forget that and stay quiet.” For Dotter, the message stuck. “For too long, I distrusted that my opinion or thought on a matter, like which witnesses should be called in a trial or how to approach an evidentiary argument. I figured that others knew better than me. But that advice is constantly in my mind and allowed me to shift my thought process to how I would in fact fail my team if I continued to distrust myself, not the other way around.”

Life Outside the Law

Away from work, Dotter enjoys competitive races, such as half—and soon to be full—marathons, as well as yoga with her closest girlfriends. She and her dog, Reese, also spend plenty of time outside enjoying the many parks, mountains, and breweries of Colorado.

When she’s not out exploring, she enjoys movies. “I’m a huge Oscars fan—so I’m always on the lookout for high-quality films with compelling directors and meaningful stories. I even host a red-carpet Oscar watch party every spring so my fellow cinephiles and I can enjoy the show together.”

When asked which films best portray the criminal justice system, she points not to movies but to two Netflix docuseries: When They See Us (2019), about the later-exonerated Central Park Five, and Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story (2024), which dramatizes the murder of the Menendez brothers’ parents.

Dotter recalls meeting Raymond Santana and Yusef Salaam of the Central Park Five. Their experience, she says, underscores “the importance of ensuring that prosecutions are based on rational and logical facts, not emotions, especially with the most tragic crimes. Their victimization by the criminal justice system should always be taught as an example of how not to investigate sexual assault.”

The Menendez story, she adds, is “a tragic but accurate portrayal of child sexual abuse. Although their murderous behaviors are not defensible in my opinion, I don’t hesitate to refer to it as an example of the depth of which sexual abuse can very easily exist in families who appear successful or happy.”

Future Plans

Looking ahead, Dotter envisions a long career of enhancing policy to improve criminal sexual assault responses and training prosecutors and the public on how to improve systemic responses to crime while upholding individuals’ constitutional rights and freedoms. Her journey reflects how early experiences can shape a career devoted to serving others—and how that work continues to elevate both the justice system and the communities it protects.