A Primer on Executive Compensation in a Colorado Divorce—Part 1

May 2022

Download This Article (.pdf)

This two-part article discusses executive compensation issues in Colorado dissolution of marriage proceedings. This part 1 covers the multistep process for characterizing and dividing executive compensation.

All marital property in a Colorado dissolution of marriage or legal separation, including executive compensation, must be divided equitably between the parties.1 However, most executive compensation, other than base salary, is awarded subject to vesting requirements or other restrictions that can make it difficult to determine whether such compensation is property or simply a mere expectancy in a divorce. But Colorado case law provides guidance to family law practitioners and judges. This two-part article offers a roadmap for characterizing and dividing various types of executive compensation. Part 1 outlines the process for (1) determining whether an award constitutes property or is a mere expectancy, (2) deciding what portion of an award is marital versus separate property, and (3) determining how best to value, divide, or allocate an award of executive compensation.

The World of Executive Compensation

As used in this article, “executive compensation” refers to benefits typically offered to highly compensated employees such as executives, officers, and directors. These benefits focus on providing rewards in exchange for results and thus differ from those generally offered to rank-and-file, hourly, or salaried employees. For example, stock options or restricted stock2 provide executives with a greater payout when a company’s stock price rises, and awards providing cash or stock where the company meets certain benchmarks (“incentive” or “performance” awards) focus on achievement over time. Executive compensation arrangements are not qualified plans,3 are often not subject to the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA),4 and usually are subject to IRC § 409A, which governs inclusion in gross income of deferred compensation under nonqualified deferred compensation plans.

This article does not address qualified retirement plans such as IRC § 401(k) plans or § 401(a) defined benefit pension plans because those plans are not linked to performance and are available to all eligible employees.

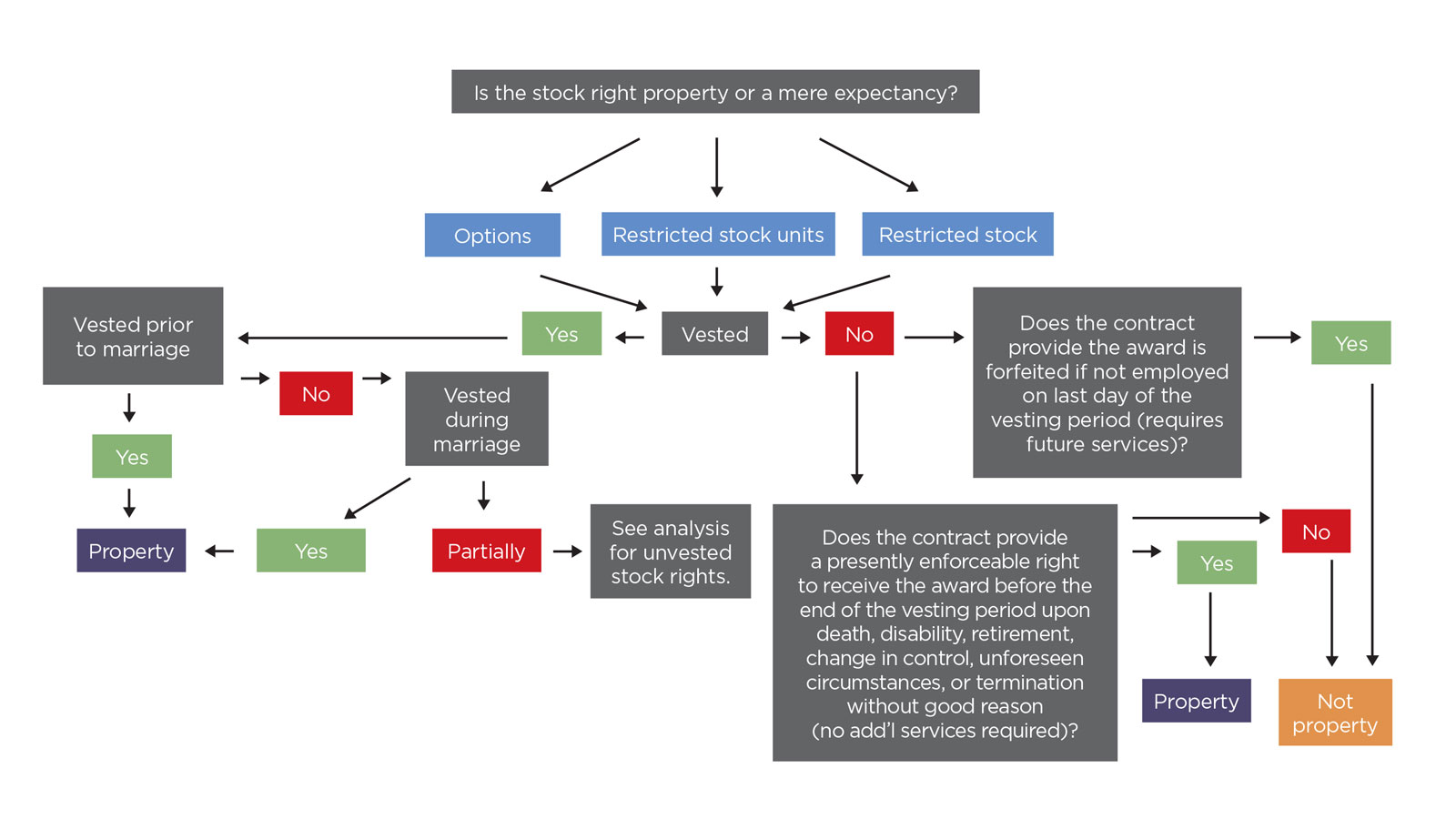

The Three Steps for Allocating Executive Compensation

The In re Marriage of Balanson line of cases includes Balanson II, which sets forth a three-step process for marital property division in Colorado.5 That process requires courts to (1) determine whether an interest constitutes “property” divisible in divorce and, if so, (2) determine whether the property is marital or separate and (3) value the marital interest for division. As relevant here, in Balanson II the husband had stock options granted in consideration for future services, and he performed approximately one year of services from the date the options were granted to the date the permanent orders entered. The trial court found that during the marriage he had the right to exercise roughly 21% of the options, which it determined to be marital property. However, at the time of the divorce the options had no value, so the court awarded all the options to the husband. The Court of Appeals upheld the award, holding that only vested stock options constitute property for purposes of property division in divorce. But the Supreme Court reversed, clarifying that in determining whether an award of stock rights is property or a mere expectancy, courts must look to the contract granting the award to see if there is an enforceable right. If an employee has a presently enforceable contract right, regardless of whether the award is presently exercisable, such a right constitutes a property interest rather than a mere expectancy. Accordingly, whether such a right is vested or unvested is not determinative.

Step 1: Is Executive Compensation “Property” Subject to Division?

Balanson II’s analysis of what constitutes property in Colorado divorce cases rested on Colorado’s Uniform Dissolution of Marriage Act (UDMA).6 The Court first recognized that in passing the UDMA, the legislature intended the term “property” to be broadly inclusive. The Court then noted it had previously defined property to include everything with an exchangeable value or that constitutes wealth or an estate.7 Further, several factors must be considered when determining whether something constitutes property: “whether it can be sold, transferred, conveyed, or pledged, or whether it terminates on the death of the owner.”8 Lastly, the Court stated that while enforceable contractual rights constitute property, interests that are merely speculative are mere expectancies. 9

Since Balanson II, in determining whether an interest constitutes property for purposes of the UDMA, courts have consistently focused on whether the employee spouse has a presently enforceable contractual right (rather than a mere expectancy),10 regardless of whether such right is presently exercisable11. The courts have thus made clear that vesting, or more properly, lack of vesting, is not determinative when characterizing stock rights.12

Which Documents Form the Contract?

IRC § 409A strictly governs most executive compensation, and there are onerous tax consequences for failing to meet its requirement that executive compensation awards be made pursuant to a written plan document. Thus, it is highly unlikely that divorce practitioners will ever have to prove the terms of an oral contract regarding executive compensation awards. On the other hand, many executives claim to be unaware of any “contract” governing their awards, so practitioners must know how to find all contract terms. Compensation committees, human resources departments, and plan administrators are aware of and have access to plan documents. At a minimum, most contracts include a plan document and an award agreement for each award. Other documents that may form a part of the contract include:

|

A Note on Vesting

The vesting concept was central to the Balanson II Court’s property analysis. A right that becomes vested during a marriage is typically property. This holds true for qualified plans such as IRC § 401(k) and § 401(a) pensions, as well as for nonqualified plans such as the executive compensation arrangements addressed in this article. The Balanson II Court’s focus on the existence of a presently enforceable right was based on what “vesting” means in nonqualified, as opposed to qualified, plans.13

In a qualified plan, vesting means ownership, and each employee owns what is vested in the plan. For example, an employee who is 100% vested in all account balances under a 401(k) owns those accounts, and the employer cannot take those benefits back for any reason. Employees who are unvested in any portion of such account balances on their termination date will not be eligible to receive the unvested portion.

Conversely, in a non-qualified plan, “vesting” is often defined to mirror, or accommodate, the rules regarding taxation of deferred compensation.14 While vesting can occur over time (e.g., one-third per year for three years) or all at once (e.g., upon completion of three years of service) for both qualified and nonqualified plans, nonqualified plans may also permit vesting to accelerate in whole or in part under specified circumstances such as death, disability, change in company control, retirement, termination not-for-cause, a pre-determined date, or an unforeseen emergency, as permitted under IRC § 409A. The existence of events under which vesting accelerates creates an enforceable right to receive the benefit, or a portion of the benefit, depending on the plan’s terms, before the end of the vesting period. Therefore, whether a property right exists under the terms of a given executive compensation plan depends on whether an enforceable right exists to receive the property before the end of the vesting period. Accordingly, it cannot be assumed that an unvested benefit is not property, and typically executive compensation that vests during marriage is property.

Based on the foregoing, to determine whether the employee has a presently enforceable right, the court must discern whether the employee completed the requisite services to enforce the right. As the Balanson II Court stated:

[I]f the contract granting the options indicates that they were granted in exchange for present or past services, in the situation for instance, where an employer offers stock options as a form of incentive compensation for joining a company, the employee, by having accepted employment, has earned a contractually enforceable right to those options when granted, even if the options are not yet exercisable. . . . On the other hand, if the options were granted in consideration for future services, the employee “does not have enforceable rights under the option agreement until such time as the future services have been performed.”15

Timing of Performance of Services

The case law on executive compensation is clear that if the compensation was granted entirely for past services, it constitutes property to be addressed in the dissolution,16 whether or not the right to executive compensation is exercisable.17 For example, if an employment contract states that options are granted as an incentive for joining the company, the employee earns a contractually enforceable right to the award upon accepting employment, even if the options are not yet exercisable.18 Similarly, if the award is made to reward an employee’s past performance on a specific project, the enforceable right arises on the date of the award, even if the award is subject to a vesting schedule.

Conversely, executive compensation granted entirely in consideration for future services that have not yet been provided is a mere expectancy and does not constitute property subject to division in a divorce.19

In practice, many executive compensation contracts have been partially performed at the time the dissolution of marriage is finalized. For example, in Balanson II, the Court found that husband had only performed the services required to enforce his right to exercise some of his options, so only those options constituted property. Accordingly, courts and practitioners must analyze whether all or part of an executive compensation award was granted for past services and constituted property at the time of the grant, even if some portion of the award is conditioned on the performance of future services.20

Where some portion of an unvested award was made to reward future services, or where the contract is unclear on whether the award was made to compensate past or future services, the next step is to determine whether the requisite services were performed to establish an enforceable right to the award.

The Contract Governs

Because executive compensation is subject to division only if the employee spouse has an enforceable contractual right, the contract governing the executive compensation is the most significant piece of evidence when determining whether the compensation constitutes property.21 In this regard, a presently enforceable right does not have to be currently exercisable to be presently enforceable. For example, a contract providing for a death benefit is enforceable even before death. Colorado cases recognize that whether an interest may be transferred (versus terminated upon the owner’s death) is one factor informing the determination of whether such an interest is property.22Analogously, divorce practitioners routinely divide survivor annuities and death benefits associated with qualified retirement plans, recognizing that such benefits are enforceable rights under the contracts creating the plans.

The Colorado Supreme Court recognized in both Balanson II and in In re Marriage of Miller that for an enforceable right to exist, an employee must have completed the requisite services to receive the interest.23 Put another way, where there is no possibility of receiving a contract benefit until all requisite services have been completed, there is no property, only an expectancy. To illustrate, consider a wife who has received 100 stock options (vesting one-third per year over three years) and 100 restricted stock units (cliff vesting after three years) where the terms are silent as to whether the awards are for past or future services. Under the governing documents, wife has a presently enforceable right to receive all unvested stock options and restricted stock units if she dies, becomes disabled, retires, quits for good reason as defined by her plan, is terminated by the employer “not for cause,” or there is a change in company control during the original vesting period. The plan provides that if one of these enumerated events occurs, the vesting of her stock options and restricted stock units will immediately accelerate, with the restricted stock units vesting 100% and the stock options becoming immediately exercisable. The fact that wife will receive her stock options and restricted stock units under these enumerated circumstances, before the end of the original vesting period, shows that she has already performed all services required for her to have a presently enforceable right. Wife, or her estate, has a right to sue the company to enforce the contract terms. The existence of this enforceable right indicates a property right.

Alternatively, consider a husband who has 100 stock options (vesting one-third per year over three years) and 100 restricted stock units (cliff vesting after three years). The terms of these awards are silent on whether they compensate past or future services. But the governing documents contain a “last day” rule under which husband is required to be employed on the last day of the vesting period to receive anything. Husband is approximately a year and a half away from this last day, and there is no vesting acceleration upon death, disability, change in control, retirement, or termination without cause. If husband’s employment terminates any time before the last day of the vesting period, he forfeits all his unvested stock options and unvested restricted stock units. Therefore, husband has no presently enforceable right to the options or stock units, and no enforceable right will arise until the vesting period ends, if he remains employed until that time. Accordingly, the unvested stock options and restricted stock units are a mere expectancy.

What About Performance-Based Compensation?

Performance-based executive compensation awards promote performance by tying the employee’s compensation to achieving measurable individual, team-based, or company-wide targets. Performance-based compensation plans include long- and short-term incentive plans and bonus plans, and they differ among employers. They can be settled in cash or stock-based awards, and while many have rolling, multiyear vesting schedules, all designate a period during which performance will be measured and tie awards to attainment of specified metrics during the performance period.

Long- and short-term incentives generally vest within one to three years. The size of the award may be contingent upon attaining a target (e.g., earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) or subject to attaining an increase in sales (e.g., 80% if sales during the performance period increase by “x,” 100% if sales increase by “y,” and 110% if sales increase by “z”). The metrics are informed by the employer’s goals. Regardless, the analysis for determining whether an incentive is property is the same as for other forms of executive compensation. And the fact that the size of the award may be reduced to zero if targets are not met does not change the characterization of the award as property or an expectancy. Equity-based compensation such as incentive awards and stock are always subject to the risk that they may have no value at the time they vest. Target goals, and the possibility of missing or exceeding them, go to the award’s value, not its characterization as a property interest.

Bonuses may be paid in cash or as stock rights such as options, restricted stock, restricted stock units, phantom stock, stock appreciation rights, or other equity award. Some bonuses are awarded pursuant to a bonus plan and may be accompanied by an award announcement, while others simply show up in the employee’s paycheck at the end of a project, a profitable quarter, or the year. Whether a bonus constitutes property does not depend on a vesting requirement. Again, the starting point is whether the employee has a presently enforceable right to receive the bonus.

For example, a bonus plan may provide that annual bonuses are paid for service in a given year, with payment to be made on April 15 of the following year, and require the employee to be employed on the last day of the year to receive the bonus. In such case, if the dissolution of marriage occurs before the end of the year in which services are provided, the employee has no presently enforceable right and thus there is no property to be divided. But if the dissolution occurs on or after January 1 of the payout year, the bonus due to be paid on April 15 is property. A presently enforceable right also exists where annual bonuses are payable pro rata to employees who terminate service without cause midyear with respect to service in a given year, with payment to be made on April 15 of the year following the year in which the services are performed.

Discretionary bonuses, or bonuses where no plan document governs, are more problematic. Whether a presently enforceable right exists will hinge on the employer’s expressed intent at the time of the permanent orders hearing. For example, if a permanent orders hearing occurs before the employer determines whether a bonus will be paid, there is no contractually enforceable right to a bonus, and the bonus is not property.24 But if the employer makes an oral promise to pay a bonus, it may be an enforceable oral contract and constitute a presently enforceable right to the bonus. 25

Deferred Compensation

Sometimes stock rights or bonuses are granted in connection with a deferred compensation plan, allowing employees to make an irrevocable election to defer receipt of the stock right or bonus until a designated point in the future. Alternatively, a stand-alone deferred compensation plan may allow employees to designate before the start of each year a portion of their base salary, bonuses, or other compensation to be deferred to a future date.

Arguably, employees who can determine when they will receive an award or compensation may be deemed to have sufficient control over the award or compensation for it to be characterized as a property right. Under the Internal Revenue Code, property or compensation deferred under a deferred compensation plan is subject to federal income tax on the earlier of the date when the property is no longer “subject to a substantial risk of forfeiture” or the date the employee has the right to transfer the property to someone else.26 As a result, most deferred compensation plans are intentionally structured to include a substantial risk of forfeiture to permit plan participants to avoid immediate taxation on amounts deferred.

But while the Department of the Treasury’s interpretation regarding what constitutes a substantial risk of forfeiture may be used to bolster an argument regarding whether there is a property right under a given deferred compensation plan, Colorado courts have not adopted “substantial risk of forfeiture” as the standard in Colorado divorces. Instead, practitioners should apply the analysis set forth above: look to the terms of the deferred compensation plan to determine whether a presently enforceable right to the deferred compensation exists.

Colorado case law is clear that compensation fully earned during the marriage but deferred until after the date of the decree is marital property.27 So employees who may forfeit compensation if their future services are not completed have no presently enforceable right, and no property right exists. Conversely, if the deferred compensation plan permits payment of an award under certain circumstances before the end of the designated deferral period, there is arguably a presently enforceable right to the award, and it should be treated as property.28

Economic Circumstance

The inquiry does not end when an executive compensation award is determined to be a mere expectancy. Courts must also consider the economic circumstances of each spouse at the time the property division is to become effective.29 While a spouse’s unvested executive compensation awards may not rise to the level of property, they may be considered in the overall division of the marital property.

And, as part 2 will discuss, stock rights, bonuses, deferred compensation, and other forms of executive compensation that are determined to be mere expectancies as of the divorce date will likely be characterized as income for support purposes once they are paid.

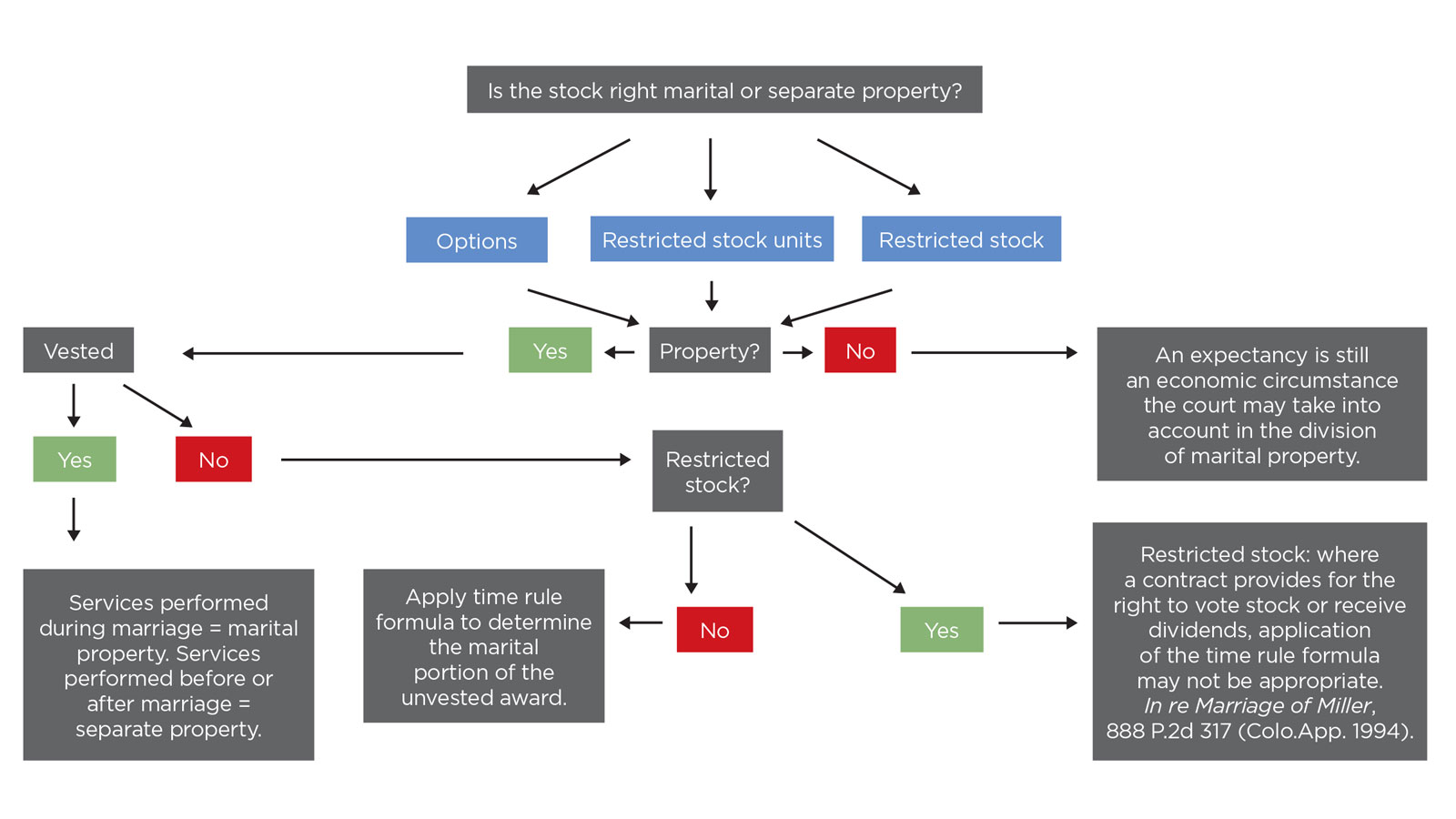

Step 2: Determining Whether Executive Compensation is Marital or Separate Property

Once an interest is deemed to be property, a court must determine whether such property is marital or separate. 31 If executive compensation is partially earned during the marriage but the decree will enter before the award vests or becomes exercisable, it must be apportioned according to the fraction that was earned during the marriage.32

Under the UDMA, there is a presumption that any property acquired by a spouse after marriage, regardless of form of ownership, is marital property.33 Four exceptions to this presumption exist for property that is (1) acquired by gift, bequest, devise, or descent; (2) acquired in exchange for property acquired before the marriage or in exchange for property acquired by gift, bequest, devise, or descent; (3) acquired by a spouse after a legal separation decree; or (4) excluded by the parties’ valid agreement.34

When dividing stock rights acquired during marriage, courts may apply the “time rule” formula or reserve jurisdiction to distribute the stock options if and when they are exercised.35 In the context of stock rights, the time rule formula is a fraction whose numerator is the number of days of service in the vesting period occurring during the marriage and whose denominator is the total number of days in the vesting period, multiplied by the number of shares or options awarded.36 In the context of incentives and bonuses, the time rule formula is applied with respect to the number of days of service during the performance period occurring during the marriage over the total number of days in the performance period. When the court establishes the marital percentage, if the value of the benefit is an unknown figure, the calculation of a dollar amount must be deferred until receipt of benefits.37

With few exceptions, the time rule formula determines what portion of an award is marital versus separate property, whether applied to stock rights, incentives, bonuses, or deferred compensation. However, there are at least two circumstances under which the time rule formula does not resolve this issue and further analysis is warranted: where there are restricted stock rights, and where marital funds are used to exercise options owned before the marriage.

Restricted Stock Rights

As to restricted stock rights, Miller38 is instructive. In Miller, husband had stock awards under the Hewlett-Packard (HP) Incentive Compensation Plan. The award agreement provided that vesting of husband’s restricted stock awards was to take place five years after the award date and would accelerate upon death, disability, or retirement based on age. Husband’s restricted stock awards also carried the right to vote the stock and to receive cash dividends with respect to the stock. An HP personnel manager testified that restricted stock awards were usually granted as bonuses for completion of a project (past services) and as incentives to employees to remain with the company (future services).

The trial court determined that the restricted stock was marital property based, in part, on the award agreement recognizing husband’s right to receive the stock early upon his retirement, disability and death,39 and it applied the time rule formula to determine what fraction of the unvested restricted stock was marital property. The Court of Appeals affirmed the trial court’s conclusion that certain employee stock options and some restricted stock shares owned by husband constituted, in part, marital property to be divided in the dissolution proceeding. In addressing whether it was appropriate to apply the time rule formula to the restricted stock shares, the Colorado Supreme Court used an “incidents of ownership” test to characterize the restricted stock rights. It upheld the determination that the restricted stock constituted marital property but determined that all of husband’s unvested restricted stock was marital property because husband owned the shares outright—HP did not have the right to repudiate the awards, and there were sufficient indicia of ownership given husband’s right to vote the restricted stock and to receive dividends on the restricted stock.

No Colorado case currently addresses whether a single indicium of ownership would be sufficient to make 100% of a restricted stock award marital, and no case has applied the incidents of ownership test to awards of restricted stock units. Accordingly, domestic relations practitioners should carefully review award contracts to determine whether incidents of ownership may affect an award as marital versus separate property.

Using Marital Funds to Exercise Options

Similarly, application of the time rule formula will not resolve whether property is marital or separate where marital funds are used to exercise options owned before the marriage. In In re Marriage of Renier, husband had stock options before the marriage that doubled due to a stock split, and he exercised them during the marriage. The Court of Appeals determined that husband’s failure to trace the source of funds used to exercise the options resulted in a presumption that all resulting shares were marital property.

Step 3: Valuing Executive Compensation for Division

The final step in the process is to value the property and divide it. Property is valued “as of the date of the decree or as of the date of the hearing on disposition of property if such hearing precedes the date of the decree.”41

Due to the uncertainty and potential volatility of stock rights, before proceeding to valuation, courts and practitioners should first determine if the awards can be divided equally between the parties, which allows them to share equally in the potential loss or gain. Where one party wishes to receive all or none of the stock rights, valuation is appropriate. Where a stock right is not transferable or divisible until after vesting, as is the case with restricted stock and many stock option awards, the stock rights may be divided if, as, and when they vest or become exercisable.42

Three methods are used to determine the division of executive compensation: current valuation, deferred distribution, and retained jurisdiction.

Current Valuation

Current valuation is used for immediate distribution of marital property where the property will not be divided in kind. Using this method, an expert values the award, considering risk and whether the award is conditioned or contingent upon future acts, and assigns a present value to the future benefit.43 Practitioners should consider the ultimate utility of such valuations before incurring the expense of an expert valuation and understand the different methods experts use.

There are two primary models for valuing stock options.44 The Black-Scholes model is widely accepted as appropriate to valuing “European” but not “American” (or “US style”) options because European options may only be exercised at a single point in time, while American options may be exercised at multiple times. The Black-Scholes model makes six assumptions. Often, more than half of its assumptions do not conform with the options available in a Colorado divorce. One such assumption is that stock options do not pay dividends or other distributions during the life of the option. However, stock plans can and do include language addressing payment of dividends during the life of the option. Further, the Black-Scholes model assumes that the short-term, risk-free interest rate is known and constant during the life of the option, but most options awarded as executive compensation in the United States are exercisable over a period of time, so the interest rate fluctuates. As a result, this method of valuation is not terribly reliable when applied to US-style options.

The second common valuation method is the binomial method. This method assumes that there are two possible outcomes in price during any given period: upward movement and downward movement. In contrast to the Black-Scholes model, the binomial method allows value to be calculated for multiple periods, and it provides a range of outcomes for each. The major difficulty with the binomial method is its complexity; it involves many calculations and variables when calculating the range of potential options values over a long period of time. As a result, a good binomial method calculation for a single stock option takes a long time to complete and can be prohibitively expensive. After undertaking this analysis, the likelihood that the binomial method will produce a value accurately reflecting the future value of an option at the time it becomes exercisable is small, and it becomes smaller as the time between the date of valuation and the date of potential exercise grows greater.

Many practitioners arrive in court or at mediation with marital balance sheets reflecting yet another valuation method: the intrinsic value of options. “Intrinsic value” refers to the difference between the strike price (exercise price) of the option and the current stock price. This method of valuing options is accurate if the options are immediately exercisable but is even less reliable than the Black-Scholes model or the binomial method because it fails to recognize the value of the ability to purchase the underlying asset at a fixed price for an extended period of time into the future. In addition, many practitioners fail to consider the cost of exercising the options and taxes associated with the options. As a result, intrinsic value, while providing a helpful data point on the day it is calculated, is generally not reflective of the true value of an option.

Deferred Distribution

Under the deferred distribution approach, the executive compensation award is held, often in a constructive trust, until it becomes transferable. In this scenario, the employee spouse continues to own the executive compensation until he or she becomes eligible to receive or actually receives the benefits.45 The trial court predetermines the percentage of the award each spouse will be eligible to receive once the right is both vested and matured.46

There is case law in Colorado stating that the proper value of executive compensation in the form of stock is the stock’s value when it is sold.47 This makes sense in cases where the plan governing the award of the stock requires that the stock be sold prior to distribution to the employee spouse. Analogously, the proper value of executive compensation in the form of deferred distribution stock options would be the value at the time the options are exercised, since that is when the value of the stock resulting from the exercise of the options is set. However, there are executive compensation plans permitting transfer of restricted stock once it is vested instead of requiring the stock to be sold upon vesting. In that case, were a court to order deferred distribution of the non-employee spouse’s share of the restricted stock to occur upon vesting, the value of stock to be divided would be determined by reference to the value of the stock on the date vesting occurs, rather than by the value on a later date of sale by either party.

Retained Jurisdiction

Lastly, courts can retain jurisdiction and reserve ruling on the valuation and allocation of the executive compensation until a future date, usually when the executive compensation is both vested and matured. This option is typically the least attractive for courts and parties because it delays final resolution of the divorce and prevents spouses from completely separating their finances at the time of the divorce.48

Conclusion

Colorado cases offer an abundance of guidance regarding the characterization and division of executive compensation in divorce proceedings. But the case law requires close reading and an understanding of different types of benefits at issue and their valuation methods. Part 2 will analyze executive compensation as income for support purposes, limitations on distribution of awards, and how to spot tax issues related to executive compensation.

Related Topics

Notes

1. CRS § 14-10-113.

2. Restricted stock is an outright award of stock issued in the grantee’s name that the grantee owns but cannot transfer until the restrictions are lifted at the end of the vesting period. On the other hand, restricted stock units are structured as an unsecured promise to transfer unrestricted shares of common stock to the grantee when the award vests in the future, at no cost to the grantee. Typically, the grantee of restricted stock units holds only a notional interest and does not receive any stock until completion of the requisite services required for vesting. Thus, restricted stock units often more closely resemble stock options than restricted stock and are often analyzed under the caselaw applicable to stock options.

3. A “qualified plan” is a tax-preferred retirement plan described in IRC § 401(a) and includes § 401(k) plans, defined benefit pension plans, and money purchase pension plans, among others.

4. Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, 29 USC §§ 1001 et seq.

5. In re Marriage of Balanson, 25 P.3d 28 (Colo. 2001) (Balanson II). In re Marriage of Balanson, 996 P.2d 213 (Colo.App. 1999) (Balanson I), and In re Marriage of Balanson, 107 P.3d 1037 (Colo.App. 2004) (Balanson III), are the two other cases in the Balanson line but do not address executive compensation issues.

6. Balanson II, 25 P.3d at 35.

7. Id. (citing Black’s Law Dictionary 1382 (4th ed. 1968)).

8. Id. (citing Graham v. Graham, 574 P.2d 75, 77 (Colo. 1978)).

9. Id. (internal citations omitted).

10. Id. at 39.

11. Id. See also In re Marriage of Cardona and Castro, 316 P.3d 626, 633 (Colo. 2014) (discussing the caselaw regarding property determinations for stock and retirement in a case involving vacation and sick leave benefits).

12. Balanson II, 25 P.3d 28, 39.

13. Id.

14. See, e.g., IRC § 409A (permitting acceleration of distribution before the end of the vesting period upon death, disability, change in control of the company, retirement, termination of employment not-for-cause, a predetermined date or fixed schedule, or unforeseen emergency) and IRC § 83 (subjecting executive compensation in nonqualified funded plans to federal income tax when the property is no longer “subject to a substantial risk of forfeiture,” or if earlier, the date upon which the recipient has the right to transfer property to someone else). See also IRC §§ 402(b) and 403(c), providing for taxation of any “economic benefit” received as compensation, even if not paid in cash. In each case, the determination of when an employee receives taxable compensation turns on an event other than the vesting date set forth in the applicable plan.

15. Balanson II, 25 P.3d at 39–40.

16. To the extent an employee stock option or other stock right is granted in consideration of past services, it may constitute marital property when granted, but a stock award granted in consideration of future services does not constitute marital property until performance of those future services. In re Marriage of Miller, 915 P.2d 1314, 1319 (Colo. 1996); In re Marriage of Short, 890 P.2d 12, 16 (1995); In re Marriage of Malloy, No. 11CA0783 (Colo.App. June 7, 2012) (not published pursuant to C.A.R. 35(e)) (“The record here indicates that the stock retention shares were awarded for past services and that husband was entitled to exercise certain rights of ownership over them, including the right to receive dividends and to vote the shares. Applying Balanson and Miller, we conclude that husband had performed the ‘requisite services’ before the shares were awarded, and that he had a contractually enforceable right in them.”).

17. An enforceable right to stock options constitutes a property interest rather than a mere expectancy, whether or not the options are presently exercisable. Balanson II, 25 P.3d at 40. See also Cardona and Castro, 316 P.3d at 633 (reiterating the caselaw regarding property determinations for stock rights and retirement when analyzing whether accrued leave constitutes property for UDMA purposes).

18. If the contract granting stock options indicates that they were granted in exchange for present or past services, such as where they are offered as incentive compensation for joining a company, the employee, in accepting employment, has earned a contractually enforceable right to the options when granted, even if the options are not yet exercisable. Balanson II, 25 P.3d at 39.

19. There are no enforceable rights to stock options granted in consideration for future services, and such options do not constitute marital property, until the future services have been performed. Balanson II, 25 P.3d at 40; Miller, 915 P.2d 1314.

20. See also Miller, 915 P.2d at 1319 (formula trial court used did not account for the extent to which each option was consideration for past or future services; some portions of the options may have constituted marital property at the time the options were granted to the husband).

21. In determining whether an enforceable right to employee stock options exists, courts must look at the contract granting such options, and if a presently enforceable right exists, it constitutes property regardless of whether the options are presently exercisable. Balanson II, 25 P.3d at 39.

22. Graham, 574 P.2d at 77; In re Marriage of Ellis, 538 P.2d 1347 (Colo.App. 1975), aff’d, 552 P.2d 506 (Colo. 1976).

23. Balanson II, 25 P.3d 28; Miller, 915 P.2d 1314.

24. See In re Marriage of Turner, 2022 COA 39 (wife’s potential bonus, to which she did not have a contractually enforceable right at the time of the permanent orders hearing, was not property). See also In re Marriage of Ward, 657 P.2d 979 (Colo.App. 1982), and Menor v. Menor, 391 P.2d 473 (Colo. 1964), which stand for the proposition that a spouse cannot share in property that might be acquired by the other spouse after the court’s order dividing property has been entered.

25. See, e.g., In re Marriage of Johnson, 576 P.2d 188 (Colo.App. 1977) (husband’s right to receive commissions arose before permanent orders hearing and therefore was marital property subject to division).

26. 26 USC § 83.

27. In re Marriage of Huston, 967 P.2d 181, 186 (Colo.App. 1998).

28. Id. at 184.

29. CRS § 14-10-113(1)(c).

30. CRS § 14-10-115(5)(a)(I). “Gross income” includes income from any source, except as otherwise provided in subsection (5)(a)(II) (e.g., child support payments), and includes, among other things, salaries, wages, bonuses, severance pay, pensions, and retirement benefits.

31. In re Marriage of Hunt, 909 P.2d 525, 529 (Colo. 1995).

32. Id. at 534–35.

33. Id.

34. CRS § 14-10-113(2) and (3); Balanson II, 25 P.3d at 35–36.

35. Balanson I, 996 P.2d 213.

36. See Short, 890 P.2d at 15. The time rule formula is a coverture fraction that determines the marital interest in retirement benefits or stock rights. Hunt used the time rule formula to determine the portion of a military pension that was marital property. Hunt, 909 P.2d at 532. In the context of an executive compensation award, the time rule’s numerator would be the number of months of service occurring during the marriage since the date of the award and the denominator would be the total number of months of service in the vesting period.

37. Hunt, 909 P.2d 525.

38. Miller, 915 P.2d 1314.

39. Id. at 1315.

40. In re Marriage of Renier, 854 P.2d 1382, 1384–85 (Colo.App. 1993).

41. CRS § 14-10-113(5).

42. In re Marriage of Chen, 416 N.W.2d 661 (Wis.Ct.App. 1987).

43. For example, “[t]hat the husband’s full enjoyment of the benefit is conditioned on his remaining an employee affects the present value of the restricted stock shares, not their marital nature.” Miller, 915 P.2d at 1320 (citing Grubb, 745 P.2d at 665). See also In re Marriage of Nelson, 746 P.2d 1346, 1349 (Colo. 1987) (“The principles of fairness and equity, which guided our holding in Grubb that a vested but unmatured pension plan is marital property, must attend the valuation process.”).

44. Hayes, Black-Scholes Model, Investopedia, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/blackscholes.asp; Barone, Binomial Distribution, Investopedia, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/binomialdistribution.asp.

45. Hunt, 909 P.2d 525.

46. Id.

47. Huston, 967 P.2d at 185 (Court disagreed with husband’s argument that the trial court erred in valuing stock shares by using the value of the shares when sold rather than the shares’ highest price while the dissolution was pending).

48. Reserved jurisdiction cases are few. The Illinois Court of Appeals directed the trial court to retain jurisdiction until such time as options were exercised or expired. If the options were exercised, the trial court could at that time allocate the appropriate share of any profit resulting from the exercise. In re Marriage of Moody, 457 N.E.2d 1023, 1027 (Ill. 1983).

When dividing stock rights acquired during marriage, courts may apply the "time rule" formula or reserve jurisdiction to distribute the stock options if and when they are exercised.