Demystifying Colorado’s Atypical Civil and Administrative Appeals

January/February 2023

Download This Article (.pdf)

Some civil and administrative appeals in Colorado are governed by special procedural requirements. This article discusses three atypical civil and administrative appeals and summarizes the unique rules that govern them.

When faced with atypical appeals in civil or administrative cases, Colorado litigants should survey applicable deadlines, procedures, and requirements to develop an informed litigation strategy. This article explains the procedures governing three atypical Colorado civil and administrative appeals: (1) appeals of quasi-judicial decisions of local governments under CRCP 106(a)(4); (2) appeals from Industrial Claim Appeals Office (ICAO or Panel) decisions; and (3) appeals from Public Utilities Commission (PUC) decisions.1

To lay a foundation for discussing these atypical appeals, this article first provides an overview of Colorado’s appellate landscape and the typical appellate process for civil and administrative cases. It next outlines key distinctions between standard appeals and the three atypical appeals listed above.2

The “Typical” Civil Appeal in Colorado

Understanding Colorado’s general appellate landscape and the typical appellate process helps contextualize the atypical deadlines, procedures, and requirements discussed later in this article. Three levels of Colorado courts can exercise appellate jurisdiction—district courts, the court of appeals, and the Supreme Court. Within this landscape, the C.A.R. 4 “appeal as of right” is the most common appeal mechanism for civil and administrative cases.

Colorado District Courts

Colorado district courts serve as Colorado’s “trial courts of record with general jurisdiction.”3 But they also serve as intermediate appellate courts for certain classes of cases arising in other courts of first resort—like small claims courts, county courts, or municipal courts—and certain agency or government actions.4

Generally, if a Colorado district court exercises appellate jurisdiction over a matter, any subsequent appeal goes directly to the Colorado Supreme Court rather than the Colorado Court of Appeals, and the second appeal is discretionary, meaning that the Colorado Supreme Court need not accept it for review.5 Said otherwise, litigants seldom get two intermediate, as-of-right appeals in Colorado. One notable exception, discussed below, is Rule 106(a)(4) appeals, which get two “as of right” appeals and one discretionary appeal to the Colorado Supreme Court.

Colorado Court of Appeals

The Colorado Court of Appeals is the “typical” intermediate appellate court in Colorado, with a caseload of more than 2,000 new appeals and approximately 2,400 dispositions each year.6 While the court largely reviews “final judgments of . . . the district courts,” it also has jurisdiction over certain administrative decisions from state boards and agencies, including the ICAO, State Personnel Board, Colorado Medical Board, Colorado Banking Board, and Colorado Board of Education.7

Unlike the federal courts of appeals—which may entertain petitions for writs such as mandamus—the Colorado Court of Appeals has no original jurisdiction. It similarly lacks jurisdiction to issue original and remedial writs; this power is conferred to the Colorado Supreme Court by the Constitution.8

Colorado Supreme Court

The Colorado Supreme Court exercises “general superintending control over all inferior courts” in Colorado.9 Under the Colorado Constitution, our Supreme Court has both original and appellate jurisdiction.10 Unlike the court of appeals’ review of district court decisions, the Colorado Supreme Court’s review of “typical” appeals is “a matter of sound judicial discretion,” meaning that the Court can choose whether to accept review.11

Approximately 1,500 cases are filed with the Colorado Supreme Court each year.12 The Court’s caseload largely consists of discretionary appeals from Colorado Court of Appeals decisions but includes direct appeals in habeas corpus proceedings, water rights adjudications, Election Code summary proceedings, ballot title reviews, and C.A.R. 21 appeals.13

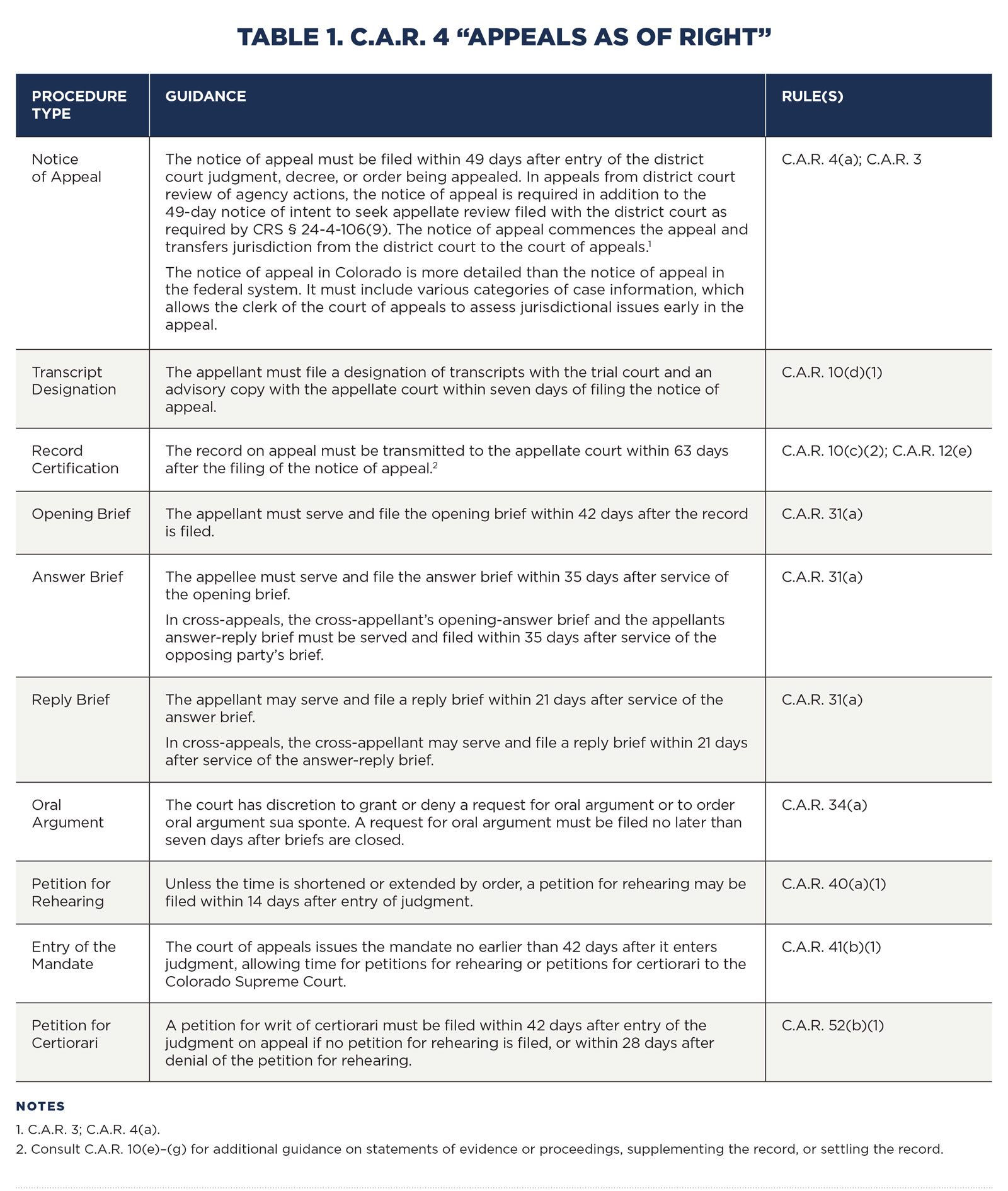

The Standard “Appeal as of Right” Under C.A.R. 4

The most common appeal mechanism in Colorado civil and administrative cases is the C.A.R. 4 “appeal as of right.” Table 1 summarizes the requirements and deadlines that generally apply in these appeals, but certain motions affect the deadline for filing a notice of appeal under C.A.R. 4. For example, timely Rule 59 motions stop the clock for filing a notice of appeal.14 However, though C.A.R. 4(a)(3)—which discusses the effect of certain post-judgment motions on the deadline for filing a notice of appeal—mentions post-judgment motions filed under CRCP 59, it is silent on post-judgment motions filed under CRCP 60.15 Therefore, while CRCP 59 motions stop the clock, CRCP 60 motions do not.16

Colorado’s Atypical Appeals

Familiarity with the applicable deadlines, requirements, and procedures is even more important when dealing with atypical Colorado appeals—those outside of “typical” C.A.R. 4 appeals as of right. While this article does not cover all such appeals, it focuses on three appeals governed by unique deadlines and procedures that Colorado litigants may encounter with some frequency.

Appealing Quasi-Judicial Decisions from Lower Governmental Entities—CRCP 106(a)(4) Appeals

If a county’s board of commissioners affirms a community development department’s decision to approve the construction of a “gravity-driven rollercoaster” over neighborhood protest, how do neighborhood residents challenge the board’s application of zoning provisions?17

Traditionally the answer might have been a writ of mandamus. When a governmental body has breached its legal duties, writs of mandamus provide an avenue of potential relief. If successful, the result of a mandamus petition is a judicial order commanding the governmental body to perform required action or correct the breach.18 This form of relief is often used when the contested decision is not issued by a court but by, for example, a city council or board of county commissioners. This makes the appellate path less straightforward.

At first blush, a litigant may believe that writs are unavailable in Colorado’s judicial system. CRCP 106—subtitled “Forms of Writs Abolished”—appears to abolish writs of mandamus in district courts. But CRCP 106 does not leave Colorado litigants without an avenue to challenge the decisions of governmental bodies whose decisions are not governed by the Colorado Administrative Procedure Act (APA) or another set of rules or procedures. Although it does away with outdated procedural requirements for traditional common law writs, CRCP 106 enables Colorado litigants to obtain the same relief a writ of mandamus would otherwise provide using simplified, straightforward procedures similar to those that govern more typical administrative appeals.19

In particular, CRCP 106(a)(4) allows interested parties to appeal the decision of any “governmental body or officer or any lower judicial body exercising judicial or quasi-judicial functions” to the district court, provided that “there is no plain, speedy and adequate remedy otherwise provided by law.”20

Colorado litigants and practitioners should be mindful of the procedures, deadlines, and requirements outlined below when appealing the decision of a governmental body under CRCP 106(a)(4).

Qualifying for CRCP 106(a)(4) appellate review. Litigants can bring Rule 106(a)(4) appeals only where the contested decision was issued by a government entity acting in a “judicial or quasi-judicial” role.21 Such “quasi-judicial” actions are taken by a government entity where a local or state law (1) requires that notice be given before the action is taken, (2) requires that a hearing be conducted before the action is taken, and (3) directs that the action results from applying prescribed criteria to the individual facts of a particular case.22 Litigants seeking to contest a government decision under Rule 106(a)(4) should consider whether the decision qualifies as “quasi-judicial” decision under these criteria. Trial courts do not have jurisdiction to review legislative or administrative actions under Rule 106(a)(4).23

Initiating the action and certifying the record. Because Rule 106(a)(4) replaces traditional common law writs, an action under Rule 106(a)(4) is initiated by filing a complaint rather than a petition or traditional notice of appeal.24

Unless another statute controls, a complaint seeking review under Rule 106(a)(4) must be filed in the district court within 28 days after the contested governmental decision.25 In drafting a Rule 106(a)(4) complaint, practitioners and litigants should note that “Rule 106(a)(4) explicitly permits the joinder of Rule 106 actions with other non-Rule 106 claims.”26 Given this, if litigants fail to include other applicable claims—for example, a request for declaratory relief—or to join applicable parties in a Rule 106(a)(4) complaint, those claims may be waived.27

Although some Rule 106(a)(4) actions may not require a record, the complaint should in most cases include a motion and proposed order requiring certification of the record from the government body where the decision under appeal originated. The court, in response, will direct the government body to file a record alongside a certificate of authenticity sometime after the deadline for filing the answer.28 Within 21 days after receipt of an order for record certification, the government body may also designate portions of the record not set forth in the order.29 At the same time the government body files the record, it must notify all parties that it has done so.30 Parties can correct the record at any time.31

If the court finds that the government body has failed to make findings of fact or conclusions of law necessary for a review of its action, the court may remand so that the government body can make such findings of fact or conclusions of law.32 During the Rule 106(a)(4) appeal, the underlying governmental decision may be stayed under CRCP 65, the rule governing injunctions and temporary restraining orders.33

Scope of the district court’s review. The standard of review for Rule 106(a)(4) actions is defined by rule. The district court’s review is limited to “whether the body or officer has exceeded its jurisdiction or abused its discretion, based on the evidence in the record.”34 The district court is therefore powerless to correct errors that do not rise to a jurisdictional overreach or abuse of discretion.35

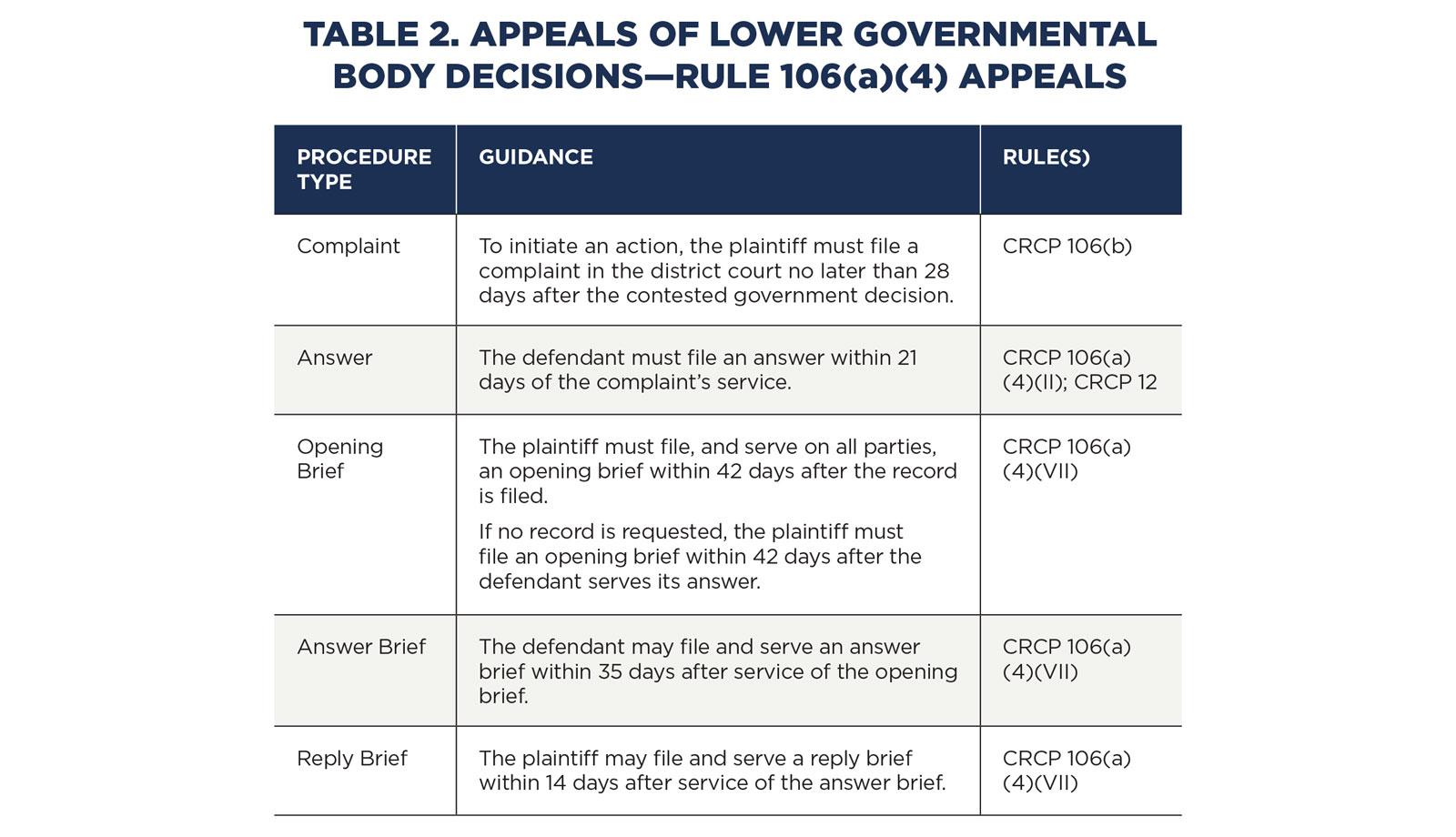

Briefing the appeal before the district court. Rule 106(a)(4) briefing deadlines are outlined in Table 2. Because some of these briefing deadlines turn on the filing of the complaint and answer, those deadlines are reproduced as well.

Appealing to the Colorado Court of Appeals. CRCP 106(a)(4) appeals are also unusual in that the district court’s appellate review does not bypass the court of appeals.36 Like the district court, the court of appeals engages in a cabined review and considers only whether the governmental body’s decision was an abuse of discretion or exceeded its jurisdiction, based on the appellate record.37 That said, because the court of appeals sits in the same intermediate appellate level as the district court, it reviews the district court’s decision de novo.38 Thus, litigants bringing CRCP 106(a)(4) appeals benefit from two intermediate appeals as of right.

Noteworthy nuances. Three additional points are of note for litigants bringing a Rule 106(a)(4) appeal. First, when a specific statute authorizes review of government decisions by writ, that review is governed by CRCP 106(a)(4).39 But if the statute authorizing the writ sets forth deadlines for review, that particular timing controls, superseding the deadlines in Rule 106(a)(4) itself.40

Second, while the Rule 106(a)(4) briefing schedule typically tracks that of the Colorado Appellate Rules, the complaint—which functions like a notice of appeal—must be filed within 28 days of the final decision from the lower body.41 This shortened time to file a notice of appeal has sometimes brought untimely ends to potentially viable claims.42 Colorado litigants should ensure that they are aware of this abbreviated timeline when considering appeals under Rule 106(a)(4). The Colorado Supreme Court recently held that equitable considerations (e.g., excusable neglect) do not factor into this “strict and jurisdictional” 28-day deadline.43

Appealing Decisions from the Industrial Claim Appeals Office

If a Coloradan is injured while working but is denied workers’ compensation benefits, what recourse is available?44 Similarly, if a Coloradan is unable to find a job but is denied unemployment benefits, what is the next step?

Colorado’s ICAO is the unit of Colorado’s Department of Labor and Employment (CDLE) responsible for reviewing unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation decisions.45 In the first instance, ICAO hearing officers or administrative law judges (ALJs) issue initial decisions on unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation, respectively.46

An ICAO Panel of five ALJs is responsible for reviewing appeals of those initial decisions.47 At least two Panel members consider each appeal and issue a final order affirming, correcting, reversing, remanding, or setting aside the initial decision.48 The Panel’s final order is made on the record before it (i.e., without a hearing) and is the CDLE’s final action.49

Colorado workers who disagree with the Panel’s decision—or, as is sometimes the case, the lack of a decision—may appeal directly to the Colorado Court of Appeals, which has jurisdiction to review final ICAO decisions.50 These proceedings are meant to be “quick and efficient,”51 and are therefore governed by expedited deadlines, streamlined procedures, and specific remedies that are “materially different” from those in judicial proceedings.52

Initiating the action and certifying the record. There are two avenues for appealing an ICAO final order. Their applicability turns on whether the Panel has issued a written decision.

If the Panel has issued a written decision, either party may file a notice of appeal from the ICAO directly to the court of appeals within 21 days of the Panel’s final order.53 If the Panel has not issued a decision within 60 days of receiving the case file, an appeal is still available, but the deadline changes.54 In that circumstance, the appellant has 35 days after the end of the 60-day period, or an additional 14 days, to commence judicial review in the Colorado Court of Appeals.55

The notice of appeal in ICAO proceedings is slightly different from the standard civil notice of appeal. It must contain the following:56

- a complaint caption

- a case title

- the names of the party or parties initiating the appeal

- the names of all others who have appeared as parties to the agency action

- the agency case number

- a brief description of the nature of the case, including one page on the nature of the controversy

- the order being appealed

- a statement indicating the basis for the appellate court’s jurisdiction and whether the order is final for purposes of appeal

- the date of the certificate of mailing of the final order

- an advisory listing of the appellate issues

- the names, contact information, and registration numbers of the parties’ counsel

- an appendix containing agency findings, if any, and a copy of the order being appealed

- a C.A.R. 25 certificate of service showing service of the notice on all who appeared as parties before the agency and service on either the ICAO (for workers’ compensation cases) or the Division of Employment and Training (in unemployment insurance cases).

Record certification is subject to two different deadlines, depending on the subject matter of the appeal. In unemployment insurance cases, the ICAO must submit the record within 21 days. In workers’ compensation claims, the agency has more time and must submit the record within 91 days.57 Regardless of the type of case, the ICAO must arrange the record in chronological order, with all duplicates omitted, and must paginate, index, and bind the record.58

Scope of the court of appeals’ review. The court of appeals applies the same standard of review as the ICAO Panel.59 Therefore, when the ALJ’s factual findings are supported by “substantial evidence,” the court is bound by them, regardless of whether evidence is conflicting or could support a contrary result.60 Relatedly, by statute, the court may set aside an ALJ’s decision only if (1) the ALJ’s factual findings are insufficient, unsupported, or fail to support the order; (2) the record contains unresolved evidentiary conflicts; or (3) the award or denial of benefits is legally unsupported.61

Accordingly, though the court of appeals is constrained in its evaluation of the ALJ’s factual findings, it is free to revisit the ALJ’s construction or application of law.62

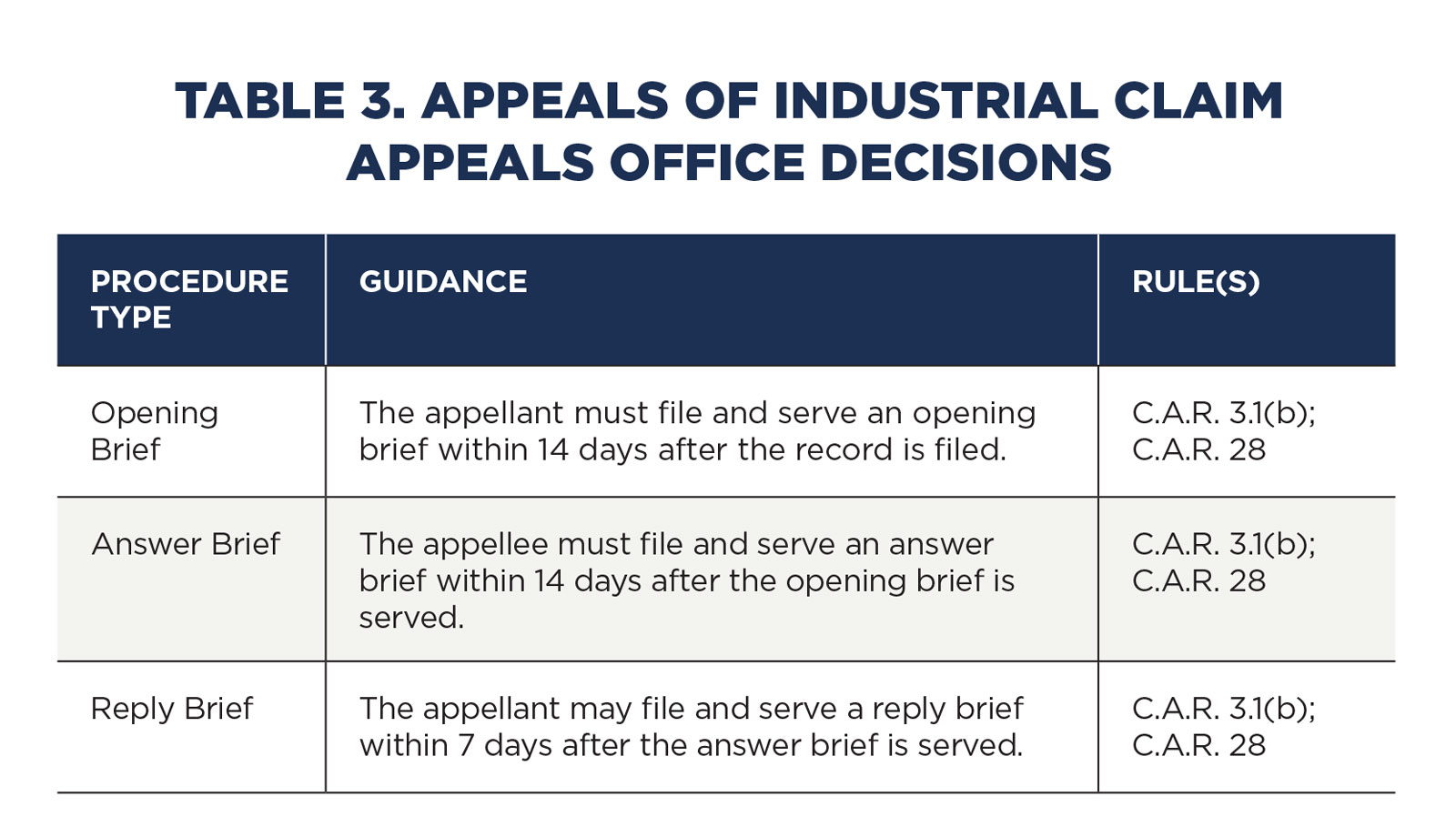

Briefing the appeal before the court of appeals. Appeals of ICAO orders are subject to the expedited briefing deadlines shown in Table 3. Other deadlines, such as the deadline for requesting oral argument, petitioning for rehearing, and entering the mandate are the same as in “typical” civil appeals.

Proceedings in the Colorado Supreme Court. After decision, if no petition for rehearing is filed with the court of appeals, dissatisfied parties may file a petition for writ of certiorari in the Colorado Supreme Court within 28 days of the court of appeals’ opinion.63 If a petition for rehearing is filed, the dissatisfied party may file for certiorari review within 14 days after the petition’s denial.64 This shortens the usual timelines, which are set forth in the table.65 The Colorado Supreme Court will engage only in a “summary review of questions of law” and must issue a decision within 60 days of granting certiorari.66

Noteworthy nuances. Two points should be emphasized for litigants appealing ICAO decisions. First, as explained above, ICAO appeals are subject to abbreviated deadlines. These deadlines should be taken seriously: The Colorado Supreme Court has declined to review appeals of ICAO decisions filed even one day after the 21-day deadline to file a notice of appeal under CRS § 8-43-301(10).67 Colorado litigants should monitor these deadlines and any statutory changes to preserve appellate challenges.

Second, and relatedly, the court of appeals will prioritize ICAO appeals over all other civil appeals.68 Colorado litigants should expect to litigate ICAO appeals on a more abbreviated timeline than might otherwise be expected.

Appealing Decisions from the Public Utilities Commission

The Colorado PUC is the unit of the Department of Regulatory Agencies responsible for ensuring that Coloradans receive safe, reliable, and reasonably priced services.69 While many appeals from state agencies go directly to the court of appeals, “[c]ases concerned with decisions or actions of the public utilities commission” are a notable exception.70 Parties dissatisfied with a PUC decision must seek intermediate appellate review with the district court.71

The PUC derives broad power from the Colorado Constitution “to regulate the facilities, service and rates and charges” of public utilities in Colorado.72 The General Assembly has further granted the PUC authority “to do all things . . . necessary or convenient in the exercise of [its constitutional] power.”73 In fulfilling these constitutional and statutory responsibilities, the PUC resolves disputes related to the following industries: electric, gas, water, telecommunications, transportation, steam, railroad, geothermal heating, pipeline transport, and gas pipeline safety. In so doing, the PUC must balance the interests of both consumers and service providers.74

The PUC may delegate its decision-making authority to an individual commissioner or ALJ.75 Those delegated decisions have the same force and effect as decisions made by the entire PUC,76 and, like decisions issued by the PUC itself, are reviewable by the district court.77

Initiating the action and certifying the record. Parties to the proceeding before the PUC may file a “writ of certiorari” with the district court within 30 days of the PUC’s final decision.78 Unlike petitions for certiorari to the Colorado Supreme Court, however, these are not discretionary; the district court is required to review the case.

The district court will issue the writ and direct the commission to certify its record within 30 days of the writ’s issuance. Unless the case is required to be continued for good cause, the district court will, if it chooses, schedule a hearing sometime after the writ return deadline.79

Appeals from PUC decisions are subject to special venue provisions. A petitioner appealing a PUC decision may choose among the district courts for (1) the petitioner’s residence, (2) the principal place of business of petitioner’s corporation or partnership, or (3) the city and county of Denver.80

The scope of the district court’s review. In reviewing the PUC’s decision, the district court will not consider new evidence.81 The court defers to the PUC’s findings and conclusions on disputed questions of fact except where a federal or state constitutional question is implicated.82 In those circumstances, the court exercises independent judgment on both the law and facts.83 Accordingly, findings or conclusions material to the PUC’s determination of constitutional questions are neither final nor subject to deferential review.84

Where no constitutional questions are implicated, the district court’s review is limited to whether the PUC has “regularly pursued its authority.”85 The PUC regularly pursues its authority when its “findings of fact and conclusions were based upon adequate evidence, and . . . the commission reached its decision by applying the appropriate constitutional and legislative standards.”86 In evaluating whether the PUC has “regularly pursued” its authority, courts view evidence in the light most favorable to the PUC’s decision.87

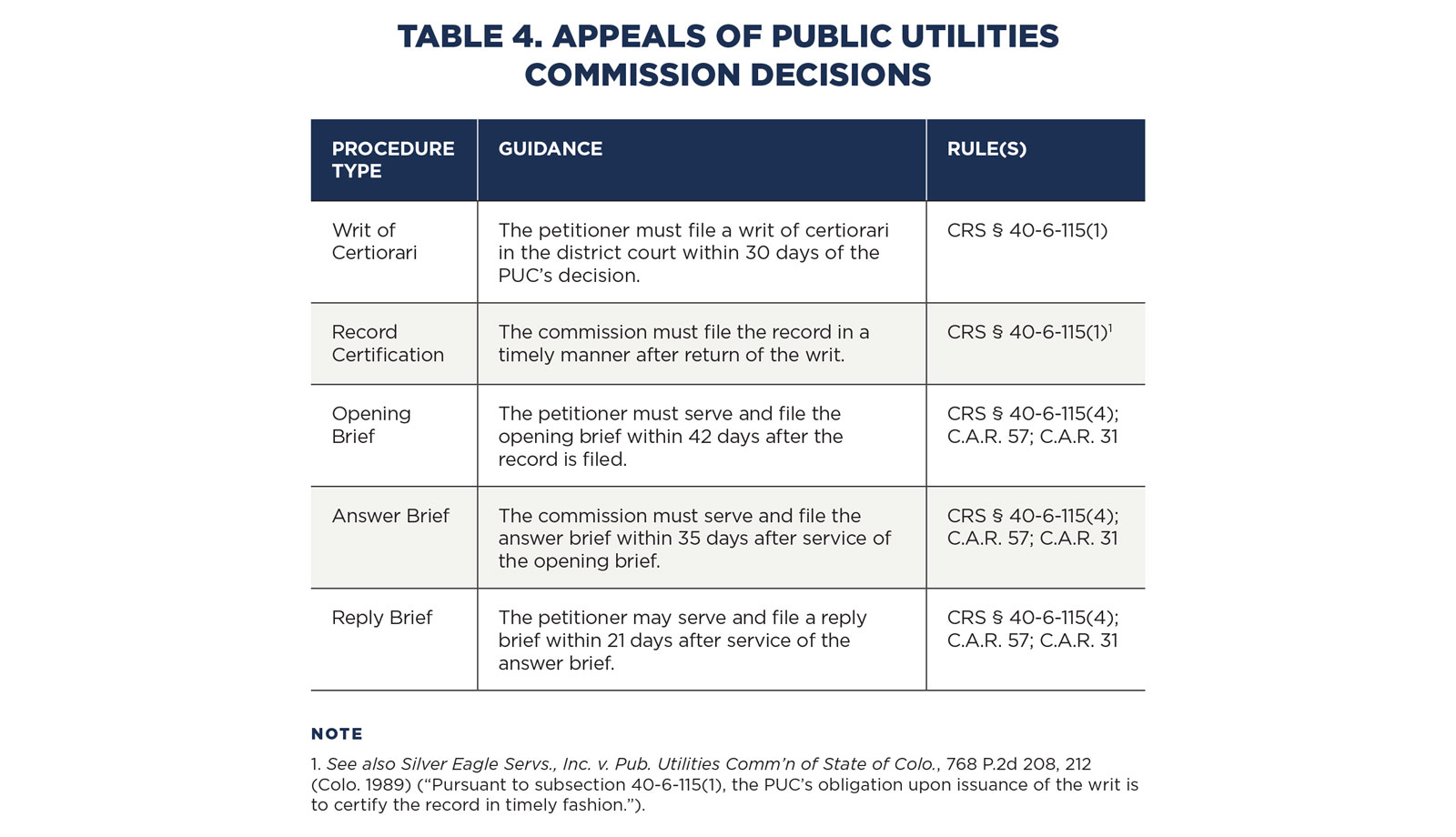

Briefing before the district court. Table 4 shows the applicable deadlines for briefing an appeal of a PUC decision. Review of PUC decisions is prioritized over all other civil causes, except for election causes, on the district court’s docket.88 Those seeking appeal of PUC decisions should be prepared to litigate on an abbreviated timeline.89

Proceedings in the Colorado Supreme Court. Unlike typical appeals in administrative cases, the Colorado Supreme Court is required to review a district court’s final decision disposing of an appeal from a PUC decision.90 Parties therefore file a notice of appeal with the Colorado Supreme Court rather than a petition for writ of certiorari.

Because the PUC “is an administrative agency with considerable expertise in the area of utility regulation,” the Colorado Supreme Court applies a deferential standard of review.91 Like the district court, the Court’s review is generally limited to determining whether the PUC has regularly pursued its authority, issued a just and reasonable decision, and reached conclusions supported by the evidence.92 But while the Court affords “deference to PUC interpretations of applicable statutes and regulations,” it reviews PUC’s interpretations of law de novo.93

Conclusion

Colorado litigants may sometimes face an appeal governed by special rules. In these circumstances, the timeline for filing a notice of appeal (or its equivalent) and subsequent briefing is often abbreviated. Other atypical procedures and requirements may also apply.

Practitioners should familiarize themselves with the applicable procedures, requirements, and deadlines that govern these atypical civil appeals in developing an informed litigation strategy. In most instances, practitioners will benefit from consulting applicable provisions of the Colorado Rules of Civil Procedure, Colorado Appellate Rules, and Colorado Revised Statutes at the outset of an atypical Colorado appeal.

This article has been updated to reflect the Colorado Supreme Court’s recent decision in Brown v. Walker Commercial, Inc.

Related Topics

Notes

1. Other atypical appeals—such as interlocutory appeals under C.A.R. 4.2, class certification appeals under C.A.R. 3.3, appeals from denials of petitions for waiver of parental notification requirements under C.A.R. 3.2, appeals from dependency or neglect proceedings under C.A.R. 3.4, and appeals from county courts—are not discussed in this article. See generally Furman et al., “Revisions to CAR 3.4 Encourage Improved Advocacy in Dependency and Neglect Appeals,” 45 Colo. Law. 49 (Oct. 2016); Masciocchi, “Hurdles to Interlocutory Review Under CAR 4.2,” 44 Colo. Law. 107 (July 2015).

2. Judicial review of agency action under the Colorado APA is beyond the scope of this article, which focuses on appeals of agency adjudications rather than judicial review under the APA. Under the APA, the court of appeals has initial jurisdiction over final decisions from a variety of agencies and agency actors, including but not limited to the State Personnel Board, Examining Board of Plumbers, and Commissioner of Insurance. See CRS § 13-4-102.

3. Colo. Const. art. VI, § 9(1).

4. See, e.g., CRCP 411(a); CRCP 519; CRCP 106(a)(4).

5. See, e.g., CRCP 411(e); C.A.R. 3.1; CRS § 40-6-115.

6. CRS § 13-4-101; Colorado Judicial Branch Annual Statistical Report: Fiscal Year 2022 at 11, 13 (2022), https://bit.ly/3WoY2dc.

7. See C.A.R. 3.2; C.A.R. 3.3; CRS § 13-4-102; Colorado Judicial Branch, Court of Appeals, https://www.courts.state.co.us/Courts/Court_Of_Appeals/Index.cfm.

8. Orman v. People ex rel. Cooper, 71 P. 430, 430 (Colo.App. 1903). See also People v. K.W.S., 192 P.3d 579, 580–81 (Colo.App. 2008) (explaining that the court of appeals has “no jurisdiction to . . . issue original writs”) (quotation omitted); People v. Richmond, 26 P. 929, 931 (Colo. 1891) (“The court of appeals is given no original jurisdiction whatever[.]”).

9. See Colo. Const. art. VI, § 2(1); Colorado Judicial Branch, Colorado’s State Court System, https://www.courts.state.co.us/Courts/Index.cfm.

10. See Colo. Const. art. VI, § 2(2) (“Appellate review by the supreme court of every final judgment . . . shall be allowed, and the supreme court shall have such other appellate review as may be provided by law.”).

11. C.A.R. 49 (“Review in the supreme court on a writ of certiorari as provided in section 13-4-108, CRS, and section 13-6-310, CRS, is a matter of sound judicial discretion and will be granted only when there are special and important reasons.”).

12. Colorado Judicial Branch Annual Statistical Report, supra note 6 at 3.

13. Id. at 2.

14. See, e.g., C.A.R. 4(a)(3) (“The running of the time for filing a notice of appeal is terminated as to all parties when any party timely files a motion in the lower court pursuant to C.R.C.P. 59[.]”).

15. Id.

16. Id. See also CRCP 59; CRCP 60.

17. See Langer v. Bd. of Comm’rs of Larimer Cnty., 462 P.3d 59, 65 (Colo. 2020) (ruling that the board of commissioners acted within its discretion in classifying a gravity-driven rollercoaster as a “Park and Recreation Facility” rather than an “Outdoor Commercial Recreation or Entertainment Establishment” and approving its development).

18. Owens v. Carlson, 511 P.3d 637, 642 (Colo. 2022) (“Mandamus is an extraordinary remedy that requires public officials to perform plain legal duties they owe by virtue of their offices.”). See also id. (explaining that mandamus is available to compel the performance of ministerial duties “involving no discretionary right,” but not “discretionary” or judgment-based tasks).

19. See, e.g., CRCP 106(a)(4)(II). See also In re People ex rel. B.C., 981 P.2d 145, 148–49 (Colo. 1999) (noting that Rule 106 abolished “the technical pleading requirements of the writs that existed before the rule” while retaining the substance of those remedies).

20. CRCP 106(a)(4).

21. Id.

22. See Baldauf v. Roberts, 37 P.3d 483, 484 (Colo.App. 2001).

23. Verrier v. Colo. Dep’t of Corrs., 77 P.3d 875, 879–80 (Colo.App. 2003) (affirming dismissal of CRCP 106(a)(4) claim challenging the constitutionality of a legislative act for lack of jurisdiction). See Stuart v. Bd. of Cnty. Comm’rs, 699 P.2d 978, 980 (Colo.App. 1985) (explaining that the trial court had no jurisdiction under CRCP 106(a)(4) to review decision that was neither judicial nor quasi-judicial).

24. CRCP 106(a)(4)(II).

25. CRCP 106(b).

26. See, e.g., Danielson v. Zoning Bd. of Adjustment, 807 P.2d 541, 543 (Colo. 1990) (observing that “a single complaint can combine claims for judicial review under C.R.C.P. 106(a)(4) and declaratory judgment claims under C.R.C.P. 57” challenging the constitutionality of a statute or ordinance). See also CRCP 106(a)(4)(VI).

27. Id.

28. CRCP 106(a)(4)(III).

29. CRCP 106(a)(4)(IV).

30. CRCP 106(a)(4)(VII).

31. CRCP 106(a)(4)(IV).

32. CRCP 106(a)(4)(IX).

33. CRCP 106(a)(4)(V).

34. CRCP 106(a)(4)(I).

35. Id.

36. See, e.g., No Laporte Gravel Corp. v. Bd. of Cnty. Comm’rs of Larimer Cnty., 507 P.3d 1053, 1060 (Colo.App. 2022) (reviewing a governmental body decision despite the district court’s intermediate appellate review).

37. Whitelaw v. Denver City Council, 405 P.3d 433, 437 (Colo.App. 2017).

38. Id. at ¶ 8.

39. CRCP 106(b). See also In re People ex rel. B.C., 981 P.2d at 149 (finding that district courts are permitted to issue writs of ne exeat because Rule 106 abolished the technical pleading requirements for such writs, but not the associated relief); CRS § 13-1-115 (“The district courts have authority in ne exeat proceedings according to the usual practice in such cases in courts of chancery.”).

40. CRCP 106(b).

41. Id.

42. See, e.g., Auxier v. McDonald, 363 P.3d 747, 753 (Colo.App. 2015).

43. Brown v. Walker Commercial, Inc., 2022 CO 57, ¶ 46.

44. E.g., SkyWest Airlines, Inc. v. ICAO, 487 P.3d 1267, 1269 (Colo.App. 2020), cert. denied, No. 20SC783, 2021 WL 965038 (Colo. Mar. 8, 2021) (affirming award of workers’ compensation benefits after determining that employee, despite being intoxicated, had returned to employment-related conduct immediately before the accident).

45. Colo. Dep’t Lab. & Emp., Industrial Claim Appeals Office, https://cdle.colorado.gov/icaowc.

46. Id.

47. Id.

48. Id.

49. Id.

50. C.A.R. 3.1; CRS § 8-43-307.

51. Sunny Acres Villa, Inc. v. Cooper, 25 P.3d 44, 48 (Colo. 2001).

52. Md. Cas. Co. v. Messina, 874 P.2d 1058, 1066 (Colo. 1994).

53. CRS § 8-43-301(10); C.A.R. 3.1.

54. CRS § 8-43-301(11).

55. Id.

56. C.A.R. 3.1(d).

57. Colorado Court of Appeals, “Appellate Checklist for Parties: Appeals from the Industrial Claim Appeals Office” at 2, https://bit.ly/3FIydOs.

58. C.A.R. 3.1(a).

59. Compare CRS § 8-43-301(8), with CRS § 8-43-308. See also Miller v. ICAO, 49 P.3d 334, 337 (Colo.App. 2001) (“The Panel and reviewing courts are bound to apply the substantial evidence test in determining whether the evidence supports the ALJ’s findings of fact.”); Metro Moving & Storage Co. v. Gussert, 914 P.2d 411, 414 (Colo.App. 1995) (“[T]he evidentiary standard of proof applied by the ALJ is not the same as the standard of review applied by the Panel and reviewing courts in determining the correctness of the ALJ’s order. By statute, both the Panel and reviewing courts must apply the substantial evidence test in determining whether the evidence supports the ALJ’s findings of fact.”).

60. SkyWest, 487 P.3d at 1272.

61. CRS § 8-43-308.

62. SkyWest, 487 P.3d at 1272.

63. C.A.R. 52(b)(2).

64. Id.

65. C.A.R. 52(b)(1).

66. CRS § 8-43-313.

67. ICAO v. Zarlingo, 57 P.3d 736, 738 (Colo. 2002).

68. See C.A.R. 3.1(c) (“All appeals from the Industrial Claim Appeals Office shall have precedence over any civil cause of a different nature pending[.]”).

69. Colo. Dep’t Regul. Agencies, Mission, https://puc.colorado.gov/pucmission.

70. CRS § 13-4-102(1)(c).

71. Compare C.A.R. 3 with CRS § 40-6-115(1).

72. Colo. Const. art. XXV.

73. CRS § 40-3-102.

74. CRS § 40-6-109.5; Colo. Dep’t Regul. Agencies, Oversight, https://puc.colorado.gov/pucoversight; Colo. Dep’t Regul. Agencies, Organization, https://puc.colorado.gov/pucorganization.

75. CRS § 40-6-101(2)(a).

76. CRS § 40-6-101(3).

77. CRS § 40-6-115(1).

78. Id.

79. Id.

80. CRS § 40-6-115(5).

81. CRS § 40-6-115(1).

82. CRS § 40-6-115(2).

83. Id.

84. Id.

85. CRS § 40-6-115(3).

86. Durango Transp., Inc. v. Colo. Pub. Utils. Comm’n, 122 P.3d 244, 248–49 (Colo. 2005) (quoting Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Ry. Co. v. Pub. Utils. Comm’n, 572 P.2d 138, 141 (1977)).

87. Trans Shuttle, Inc. v. Pub. Utils. Comm’n, 89 P.3d 398, 403 (Colo. 2004).

88. CRS § 40-6-117.

89. Id.

90. CRS § 40-6-115(5).

91. Integrated Network Servs., Inc. v. Pub. Utils. Comm’n, 875 P.2d 1373, 1377 (Colo. 1994).

92. Pub. Serv. Co. v. Trigen-Nations Energy Co., 982 P.2d 316, 322 (Colo. 1999). See also CRS § 40-6-115(2)–(3).

93. Trigen-Nations Energy Co., 982 P.2d at 326; CRS § 40-6-115(2)–(3).

Three levels of Colorado courts can exercise appellate jurisdiction—district courts, the court of appeals, and the Supreme Court. Within this landscape, the C.A.R. 4 ‘appeal as of right’ is the most common appeal mechanism for civil and administrative cases.