Non-Compete Agreements in Colorado

A New Era

November 2022

Download This Article (.pdf)

This article discusses the current scope of the non-compete statute and enforceability of non-compete agreements. It also provides related considerations for both workers and employers.

The use of non-compete agreements by employers in Colorado is a perennial and thorny issue for Colorado employers and employees—and the lawyers who represent them. Extensive amendments to the non-compete statute, including new criminal and civil penalties, have complicated the playing field even more. Many unanswered questions remain regarding how courts will evaluate non-compete agreements and enforce related criminal and civil penalties in light of the recent amendments, which became effective August 10, 2022. This article provides an overview of Colorado’s non-compete statute and offers practical tips for employers and employees considering a non-compete agreement.

Types of Non-Compete Agreements

Colorado has long prohibited most agreements restricting an employee’s ability to engage in any lawful occupation and receive compensation for work performed.1 Colloquially, these agreements are known as “non-competes,” though they often include one or more broader restrictive covenants that (1) prevent a former employee from working for a competitor for a particular amount of time; (2) prevent a departing employee from soliciting other employees to join them in moving to a competitor; or (3) prevent employees from disclosing a former employer’s proprietary information.

State law typically governs non-competes. The question of which state’s law applies is ordinarily governed by the law of the state where the restraint will be imposed—usually the state where the employee primarily lives and works. Policy considerations surrounding non-competes include the state’s public policy protecting the mobility of its workers, the nature of the former employer’s business interests, whether a specific amount of consideration was given for the restriction, and the scope of the restrictions. Restrictions tailored for both duration and geography are viewed more favorably by courts. In general, non-compete agreements are void under Colorado law, with limited exceptions.

The amended non-compete statute significantly limits the enforceability of non-compete agreements and post-termination restrictions that apply to workers primarily working and living in Colorado. Under the recent amendments, if a worker primarily resides and works in Colorado as of the date of their termination, the non-compete or non-solicitation agreement cannot require adjudication of the enforceability of such agreement outside of Colorado.2

Additionally, while the statute does not explicitly address independent contractors, the amended statute protects “workers” instead of “employees.”3 As a result, the amended statute likely will apply to independent contractors, consultants, and other individuals who perform work for another.

Summary of Colorado’s Non-Compete Statute

Colorado law makes it unlawful “to use force, threats, or other means of intimidation to prevent any person from engaging in any lawful occupation at any place he sees fit.”4 With a few exceptions, Colorado non-compete and non-solicitation agreements are now generally void unless they apply to “highly compensated” employees who meet certain salary requirements, are for the protection of trade secrets, and are not broader than reasonably necessary for the protection of trade secrets.5 This replaces the provision in the statute that previously allowed non-competes for executive and management personnel and their professional staff (with no compensation restriction).

The salary thresholds for “highly compensated” workers are set by Colorado’s Department of Labor, increasing proportionately for inflation. A non-compete agreement can only be enforced against a worker who earns at least $101,250 annually (or the adjusted salary threshold then in effect). A non-solicitation agreement is only enforceable against a worker who earns at least 60% of the “highly compensated” threshold (currently $60,750), both at the time the agreement is entered into and at the time it is enforced.

In addition, the following four covenants are allowed:6

- A provision providing for an employer’s recovery of the expense of educating and training a worker where (1) the training is distinct from ordinary on-the-job training; (2) the employer’s recovery is limited to the reasonable costs of the training and decreases over the course of the two years subsequent to the training proportionately based on the number of months that have passed since the completion of the training; and (3) the employer recovering for the costs of the training would not violate the Fair Labor Standards Act, 29 USC §§ 201 et seq., or article 4 of title 8.

- A reasonable confidentiality provision relevant to employer’s business that does not prohibit disclosure of (1) information that arises from the worker’s general training, knowledge, skill, or experience, whether gained on the job or otherwise; (2) information that is readily ascertainable to the public; or (3) information that a worker otherwise has a right to disclose as legally protected conduct.

- A covenant for the purchase and sale of a business or the assets of a business.

- A provision requiring an individual working in an apprenticeship to repay a scholarship if the individual fails to comply with the conditions of the scholarship agreement.

Because non-compete agreements are disfavored in Colorado, the exceptions are narrowly construed.7

Notice Requirement

The new statute voids any non-compete agreement where the employer fails to give the employee proper notice of the agreement along with a summary of the agreement’s restrictive terms.8 For prospective workers, the notice must be provided before the applicant accepts an offer of employment.9 For current workers, the notice must be given at least 14 days before the earlier of either (1) the effective date of the non-compete agreement, or (2) a change of the condition of employment providing consideration for the agreement.10 The notice must be in a standalone agreement—it cannot be included in a general policy, handbook, or employment contract.11 Finally, the worker must sign the agreement.12

Provisions for Physicians

Colorado law also voids covenants not to compete provisions in employment, partnership, or corporate agreements between physicians that restrict the right of a physician to practice medicine.span 13 However, such agreements may require payment of damages in an amount reasonably related to termination of the agreement.14 The newly amended statute carves out an exception to this restriction: physicians may now disclose their new professional contact information to any patient with a rare disorder whom the physician was treating prior to termination of the agreement.

Evaluation of Non-Compete Agreements

A non-compete agreement that fails to meet one of the statutory exceptions is facially void, rather than voidable.15 In other words, a party to a non-compete agreement that does not fall under one of the specific statutory exceptions should not need to obtain a judicial declaration that the agreement is void—such an agreement is unenforceable on its face. Regardless, the revised statute provides that a party to a covenant not to compete, or a subsequent employer that has hired or is considering hiring the worker, may seek a declaratory judgment from a court or arbitrator that the covenant not to compete is unenforceable.16

Non-Competes Must Still Be Geographically and Temporally Reasonable

Even if a non-compete agreement is otherwise enforceable, it must be reasonable as to both duration and geographic scope.17 Non-compete agreements must not be broader than necessary to protect the employer’s legitimate interests and must not impose hardship on the worker.18 While reasonableness is a fact-intensive inquiry, covenants not to compete with terms of up to five years and within a distance of 100 miles have been upheld.19 However, the Colorado Court of Appeals found that a non-compete agreement was unenforceable where it would have required an anesthesiologist to move or pay damages in order to practice his profession.20 The court concluded that the non-compete was unreasonable and imposed a hardship under those circumstances.21

In general, the broader the geographic scope of the non-compete, the shorter the duration of the restriction should be. The converse is also generally true. If a company wants to enforce a non-compete of longer duration, the geographic scope should be narrow. In all but quite unusual circumstances, nationwide and international restrictions are likely to be viewed with considerable skepticism by the courts. Even statewide restrictions may be met with a jaundiced eye given the implications to the worker. Given the tendency of many workers to buy homes near their work, send children to school, and otherwise plant roots in the community, courts are likely to view such agreements as unreasonable and to require a compelling case for why the restriction is necessary. Although Colorado courts have not set a bright-line rule for the geographic and temporal scope of non-compete agreements, restrictions of durations longer than a year or two are uncommon.

The Recognized Exceptions

Despite the recent amendments, Colorado law still recognizes several exceptions to the general prohibition against non-competes.

Educating and Training a Worker

Very few cases discuss the exception allowing an employer to recover expenses for educating and training a worker who has served the employer for less than two years. However, at least some courts have suggested that ordinary on-the-job training that does not put the employee in a position to compete unfairly is insufficient to uphold a reimbursement provision.22 This exception to the general rule voiding most non-compete provisions is more likely centered on employer-sponsored programs that cover the cost of a worker’s outside educational endeavors, such as earning a degree or a certificate. It stands to reason that if an employer is willing to pay a worker to obtain a specific credential—for example, an accounting degree or an MBA—then the employer has an interest in ensuring that the worker stays employed by the company for a reasonable amount of time. This exception sets that period at two years. Open questions remain regarding what type of training is covered by this exception. A good rule of thumb is that the more formalized the program, the more likely it would be covered by this provision. By contrast, the less formal and more akin to on-the-job training, the less likely this exception would apply.

Confidentiality Provisions

Cases decided before the amendments outlined a two-part test requiring courts to determine whether (1) the facts justified the restrictive covenant (i.e., there was actually a trade secret to protect); and (2) the specific terms were reasonable.23 In other words, non-competes were only enforceable if they were designed to protect trade secrets and reasonably limited in scope.24

Now, a confidentiality provision may be enforceable if it is reasonable, relevant to the employer’s business, and does not prohibit disclosure of certain information, including (1) information arising from the worker’s general training, knowledge, skill, or experience, whether gained on the job or otherwise; (2) publicly available information; or (3) information that a worker otherwise has a right to disclose.25 The meaning and scope of “reasonable,” “relevant to the employer’s business,” and “general training, knowledge, skill, or experience” are potential issues for litigation.

Like the terms in the new confidentiality provision, what qualifies as a trade secret is subject to interpretation. In Management Recruiters of Boulder v. Miller, the Colorado Court of Appeals affirmed the trial court’s determination that a one-year restriction on contacting candidates was enforceable when the candidate information was a trade secret.26 But companies should be cautious in how broadly they construe what constitutes a trade secret. Not every piece of business information—confidential or not—meets the definition of a trade secret.27

Given the exception’s inclusion of certain categories of information, as opposed to merely trade secrets, a broader swath of confidential information may be protected under the exception in CRS § 8-2-113(3)(b) without the need to prove trade secret status. The restrictions must be reasonable, however, and the exceptions in CRS § 8-2-113(2)(b) and (d) still explicitly refer to trade secrets in the context of employment and non-solicitation restrictions.

Purchase and Sale of Business

The reasonableness of non-compete agreements related to the sale of a business turns on whether the restraint provides fair protection to the buyer’s good will and imposes no greater restrictions than necessary to protect the value of the good will.28 In the former statute, even non-signatories to an agreement could be bound by a non-compete clause based on their particular relationship to the business.29 But given the amended statute’s notice and signature requirements, prior law is in doubt.30 Further, a non-compete agreement is no longer enforceable after the initial business ceases to exist.31

Scholarship Repayment

Colorado’s non-compete statute has separate requirements regarding business apprentices. A provision requiring an apprentice to repay a scholarship if the apprentice fails to comply with the terms of the agreement is not prohibited.32

Criminal and Civil Penalties Against Employers

The revised non-compete statute attempts to eliminate confusion from the previous version, which stated that any violation of the statute would result in a class 2 misdemeanor. Significantly, as of August 10, 2022, a criminal penalty applies to attempts to unlawfully intimidate workers to prevent them from engaging in a lawful occupation.33 Any person who violates this law commits a class 2 misdemeanor.

Though the revised statute may not criminalize asking a worker to sign an invalid non-compete agreement, civil penalties may apply. The statute states that “[a]n employer shall not enter into, present to a worker or prospective worker as a term of employment, or attempt to enforce any covenant not to compete that is void under this section [8-2-113].”34 An employer that violates this mandate is liable for civil penalties in the form of actual damages, reasonable costs, attorney fees, and $5,000 per worker, or any prospective worker, harmed by the violation.35 The law includes a private right of action to enforce the statute and seek injunctive relief, and the attorney general may seek the same relief on behalf of individuals.36 But the revised statute includes an employer safe harbor provision granting a court discretion to award no or reduced penalties when the employer acted in good faith and had reasonable grounds for believing the employer’s act or omission was not a violation.37

Considerations for Workers and Employers

The recent amendments should prompt both Colorado employers and workers to examine existing and future non-compete agreements. The following are key takeaways:

- Existing agreements: Employers should carefully review any existing non-compete agreements to ensure compliance with the law. Workers who signed a non-compete should re-read it now. Any party who suspects a problem should consult with competent legal counsel.

- Future agreements: Employers should consider whether a non-compete agreement is necessary for the specific worker and, if so, how best to tailor the agreement to comply with the statute. Workers should carefully read any agreement presented to them by their employer and should not simply assume the agreement is enforceable.

- Enforcement: Employers should bear in mind the potential civil and criminal penalties for a violation of the statute. Workers should weigh the risks and rewards of signing or challenging a non-compete agreement.

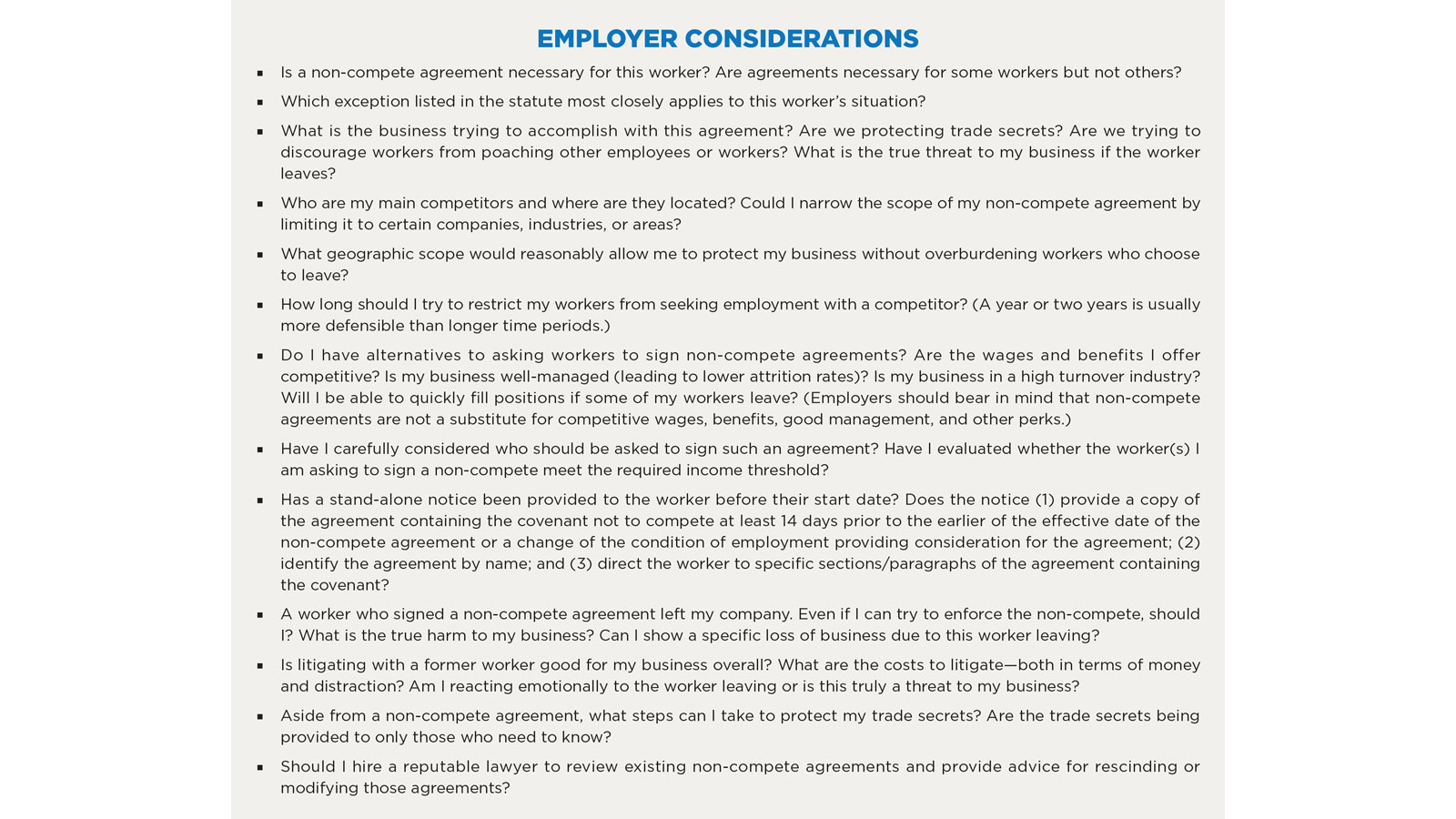

- In addition, employers and workers should ask themselves a series of in-depth questions when evaluating such agreements. Some key questions are listed in the sidebars.

Conclusion

Amendments to Colorado’s non-compete statute bring additional restrictions, requirements, and potential penalties. Employers wishing to place certain restrictions on employees must understand the parameters and notice requirements imposed by the changes to the law. Likewise, employees should carefully read their employment agreement and understand any limitations or conditions in the agreement.

Related Topics

Notes

1. Colorado’s non-compete statute, CRS § 8-2-113, dates back to 1963.

2. CRS § 8-2-113(6).

3. See HB 22-1317 (codified at CRS § 8-2-113).

4. CRS § 8-2-113(1.5).

5. CRS § 8-2-113(2)(b).

6. CRS § 8-2-113(3)(a) to (d).

7. Gold Messenger, Inc. v. McGuay, 937 P.2d 907, 910 (Colo.App. 1997).

8. CRS § 8-2-113(4)(a).

9. Id.

10. Id.

11. CRS § 8-3-113(4)(b).

12. Id.

13. CRS § 8-2-113(5)(a).

14. Id.

15. Management Recruiters of Boulder, Inc. v. Miller, 762 P.2d 763, 765 (Colo.App. 1988); Phoenix Cap., Inc. v. Dowell, 176 P.3d 835, 840 (Colo.App. 2007).

16. CRS § 8-2-113(7).

17. Nat’l Graphics Co. v. Dilley, 681 P.2d 546, 547 (Colo.App. 1984).

18. Crocker v. Greater Colo. Anesthesia, P.C.,

463 P.3d 860, 865; Reed Mill & Lumber Co. v. Jensen, 165 P.3d 733, 736 (Colo.App. 2006); Whittenberg v. Williams, 135 P.2d 228 (Colo. 1943).

19. Reed Mill & Lumber Co., 165 P.3d at 736; Harrison v. Albright, 577 P.2d 302, 305 (Colo. App. 1977). See also Mgmt. Recruiters of Boulder, Inc., 762 P.2d at 766 (upholding one-year restriction).

20. Crocker, 463 P.3d at 865.

21. Id.

22. CRST Expedited, Inc. v. TransAm Trucking, Inc., 505 F. Supp. 3d 832, 841 (N.D. Iowa 2020) (discussing Ag Spectrum Co. v. Elder, 865 F.3d 1088 (8th Cir. 2017)).

23. Mgmt. Recruiters of Boulder, Inc., 762 P.2d at 766.

24. Saturn Sys. v. Militare, 252 P.3d 516, 526 (Colo.App. 2011); Gold Messenger v. McGuay, 937 P.2d 907, 910-11 (Colo.App. 1997).

25. Id.

26. Mgmt. Recruiters of Boulder, Inc., 762 P.2d at 766.

27. An in-depth discussion of what constitutes a trade secret is beyond this article’s scope. For more information, see the Colorado Uniform Trade Secrets Act, CRS §§ 7-74-101 to -110 and interpretative case law, including Gold Messenger, 937 P.2d at 911 and Colo. Supply Co. v. Stewart, 797 P.2d 1303, 1306 (Colo.App. 1990).

28. Reed Mill & Lumber Co., 165 P.3d at 736; Barrows v. McMurtry Mfg. Co., 131 P. 430 (Colo. 1913) (an agreement that arbitrarily binds the seller beyond the duration and geographical scope necessary to protect the good will transferred is without consideration).

29. See Gold Messenger, 937 P.2d at 912.

30. CRS § 8-2-113(4).

31. See Gibson v. Eberle, 762 P.2d 777, 779 (Colo.App. 1988).

32. CRS § 8-2-113(3)(d).

33. CRS § 8-2-113(1.5)(a).

34. CRS § 8-2-113(8)(a).

35. CRS § 8-2-113(8)(b).

36. Id.

37. CRS § 8-2-113(8)(c).

Given the exception’s inclusion of certain categories of information, as opposed to merely trade secrets, a broader swath of confidential information may be protected under the exception in CRS § 8-2-113(3)(b) without the need to prove trade secret status.