Proving Covered Personal Property Loss Under a Homeowners Policy

October 2022

Download This Article (.pdf)

This article discusses common problems homeowners face when filing claims to access their insurance coverage for personal property loss following the catastrophic loss of a home by fire, flood, or otherwise.

On December 30, 2021, the Marshall Fire, fueled by steady 100 mile-per-hour straight-line winds, scorched Louisville, Superior, and unincorporated Boulder County, killed two people, and destroyed nearly 1,000 homes.1 Among the many profoundly sad scenes following that conflagration was that of people picking through their homes’ ash and rubble to create an inventory of their burned personal property. Capable of exceeding 5,000 degrees,2 home fires often destroy personal property or render it unrecognizable. Most home insurance policies include automatic coverage for personal property (contents) loss with payment limits equal to some percentage of the overall dwelling limits.3 In Colorado, when a home’s contents are completely destroyed by fire, homeowner insurers are required to pay 30% of the personal property limits without any proof of the nature, condition, or value of the lost property.4 With a little arm-twisting, the Colorado Division of Insurance persuaded many insurers to pay a much higher percentage to homeowners affected by the Marshall Fire.5 But generally, to receive payment above that statutory minimum, homeowners must establish additional personal property loss per their policy’s terms.

This article examines the typical insurance coverage applicable to the destruction of a homeowner’s personal property due to fire, flood, or some other catastrophic event. It discusses problems inherent in establishing a covered personal property loss and provides practical tips for addressing them. It also suggests steps to take to maximize coverage when buying homeowners insurance, including establishing the pre-loss existence, condition, and value of the property, and securing more expansive insurance protection.

Common Coverage and Proof Problems

Establishing personal property loss following the loss of a home is no easy task. Homeowners generally must prove what personal property was present when the home was destroyed, the property’s age and condition, the availability of “like kind and quality” replacement personal property, and the property’s depreciated value and actual replacement cost. Moreover, most policies impose sub-limits that apply to particular kinds and classes of property, such as cash, silverware, valuable collections, and certain business property. Coverage limitations or exclusions also may apply to items with sentimental or unique value, such as wedding albums, family heirlooms, and antiques.

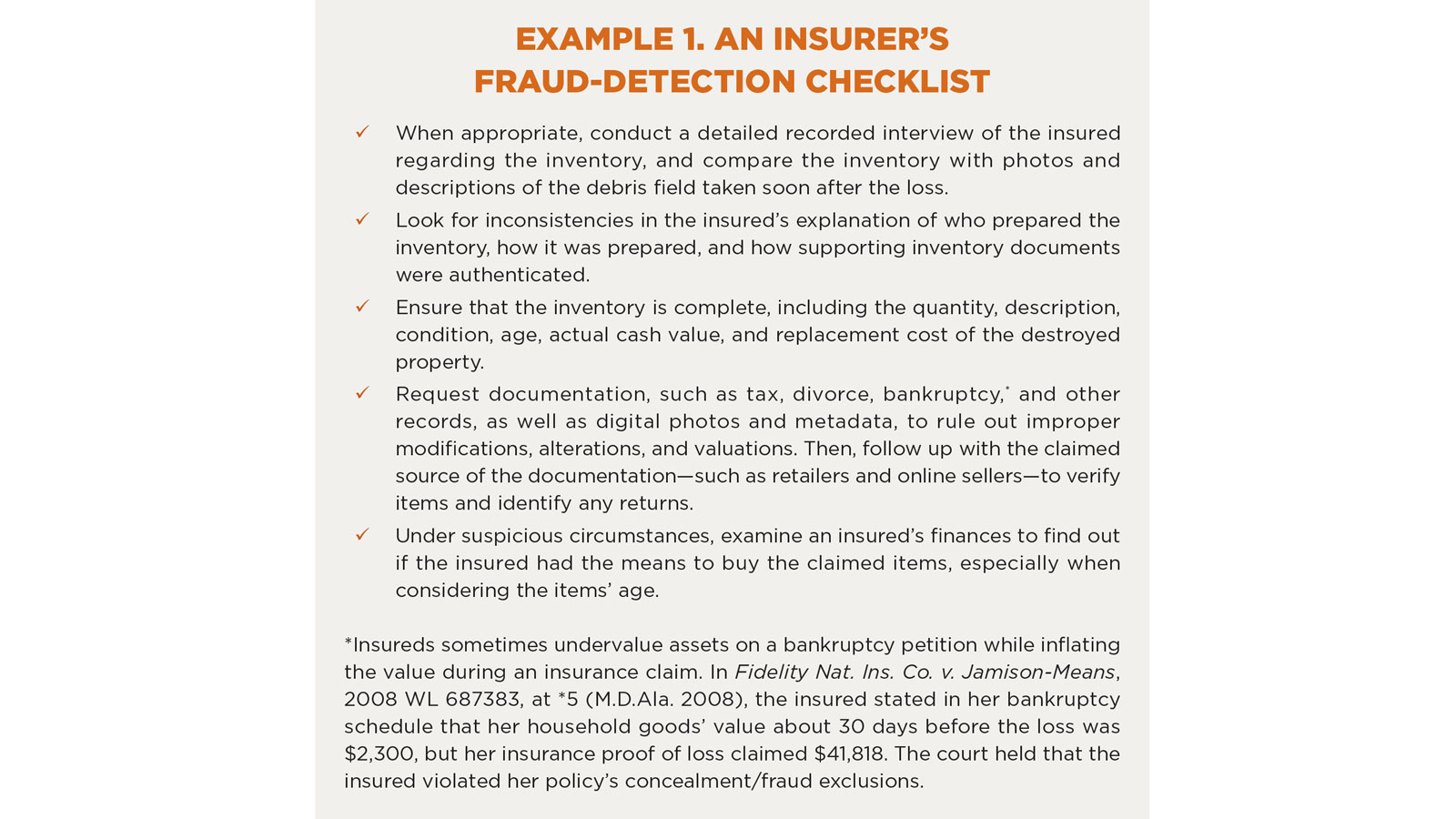

Creating a personal property inventory from memory, random family photos, electronically stored purchase records and credit card receipts, remnants found in the rubble, and so on can help complete a personal property inventory post-loss, but compiling such inventories is time-consuming and heart-rending, may be imprecise and incomplete, and could cause inadvertent duplications. These uncertainties can lead an insurer to contend that some of the claimed inventory is fraudulent and seek to void some or all of the policy’s coverage.6 Because such inventories may consist of thousands of line items, the risk of accidental duplication or error is almost unavoidable, so the risk of an insurer raising a fraud defense cannot be eliminated. Example 1 lists some common loss-adjustment strategies employed by insurers and “badges of fraud” they may flag.7

Policy Language

Several aspects of homeowners insurance policies are typically implicated in catastrophic personal property loss claims: (1) the policy declaration’s monetary limits for the personal property (contents) coverage; (2) the policy’s specified sub-limits and exclusions for certain kinds and classes of personal property; and (3) the policy’s loss settlement and appraisal provisions. Example 2 contains some common provisions, but the exact policy language often varies considerably among policies. (Discussion of third-party appraisal provisions, typically triggered when the policyholder and insurer disagree on the amount of the loss, is beyond this article’s scope.)

Example 2. Common Policy Provisions

How Losses Will be Paid—Loss Settlement

Personal Property Excluded from Coverage

Personal Property Subject to Sub-limits

*HB 22-1111 mandates that policies provide, in the event of a declared wildfire disaster, an extended period to replace destroyed personal property and recover depreciation where the property is destroyed equal to 365 days after the expiration of the policy’s alternate living expense period or 36 months after the insurer provides its first payment toward the property’s ACV. CRS § 10-4-110.8(13)(d). |

Key Policy Terms

“Replacement cost” generally means the cost to replace personal property with new property of like kind and quality materials, goods, or products. “Actual cash value” or “ACV” typically means the replacement cost less depreciation. “Depreciation” usually refers to a property’s loss of value due to age, wear, deterioration, use, or obsolescence. Depreciation should not be taken on a partial loss where the property can be repaired or restored.8

Actual Purchase Requirement Before Full Replacement Cost Reimbursement

The use of the term “replacement cost coverage” in many policies may be misleading because most policies require the insured to first replace the property as a condition precedent before the full replacement cost becomes payable. This means the insured must secure the necessary funds to buy the item and then seek reimbursement of the difference between the item’s ACV and its replacement cost.9 Courts have held that an insurer is not obligated to pay for claimed personal property loss where the insured’s demand is based solely on the property’s replacement cost and the item’s actual replacement has not occurred—unless the policy provides true unconditional replacement cost coverage.10 Replacement cost coverage is sometimes referred to as “new for old,” because it entitles the insured to replace old property with new property.11

Like Kind and Quality

Most policies require that an insured replace destroyed property with property of “like kind and quality.” This does not equate to a precise duplicate of the destroyed property, just substantial similarity and use. Few cases have explained how to judge similarity of kind and quality when no comparable item can be found.12 An insurer’s insistence on an insured replacing destroyed property with identical property may be unreasonable if the policy only requires replacement with like kind and quality property. It is advisable to try to get an insurer to agree ahead of time how closely a new replacement item (such as a new Sony TV) must resemble the destroyed item (such as an older LG TV) both for ACV and replacement cost purposes. One frequently employed restriction—the “functional personal property valuation” limitation or endorsement—limits the insured’s replacement cost recovery to the smallest of (1) the limit of insurance; (2) the cost to replace, on the same site, the lost or damaged personal property with the closest equivalent property available; or (3) the amount the insured actually spends to repair or replace the lost or damaged personal property.13

Goods No Longer Available

If the destroyed personal property is no longer made or available after the loss occurs, most policies allow its ACV or replacement cost to be calculated using property of like kind and quality.

Obsolete and Sentimental Goods

Challenges may arise when valuing obsolete goods and sentimental items.14 Old computers, typewriters, and other aged electronic equipment that have become obsolete may be unwittingly assigned an inflated value. An insured may also overvalue items that have a family history or sentimental importance, such as heirlooms and handmade items handed down from prior generations, family photographs or picture albums, baby clothes, and wedding dresses. The insured may attach great emotional value to the item that does not match its actual value. Under a true unconditional replacement policy, however, the insurer may be obligated to pay what is necessary to replace the item with one of like kind and quality unless the policy provides otherwise, which some do for certain antiques and collectibles.

Electronic Data and Other Unique Personal Property

Electronic data may be difficult and expensive to duplicate. For example, recompiling financial records, digital photos, and the like may require exceptional efforts and may not even be possible. In many instances, no amount of effort or expense could recreate the lost data. Most policies exclude payment for recreating the data itself and limit recovery to the cost of the raw media storage product.

Soot, Ash, Smoke, and Char Damage

This article assumes a claim is being made for personal property destroyed by fire, but what about smoke-damaged property? Most policies cover “all risks of physical loss,” which typically includes soot, ash, smoke, and char damage from fire.15 And payment for smoke damage to household items such as area rugs, clothing, curtains, and furniture usually falls under one’s personal property coverage.16 Still, parties may dispute whether items are salvageable or have been so charred or saturated with soot, ash, or smoke that they are essentially destroyed (i.e., unsafe, unsanitary, or otherwise unusable or aesthetically spoiled) and not economically reparable.17 Fire particulates, including some impregnated with unhealthy synthetic chemicals, can easily infiltrate and permeate a home and all its soft and hard goods and furnishings, often in ways not visible to the eye. Cleaning may not be cost-beneficial or even feasible. An experienced certified industrial hygienist or indoor air quality specialist may need to establish and quantify the extent and severity of, and health risks posed by, such damage. If cleaning is unsuccessful, recovery for both the cleaning expense and the replacement property could be available.

Typical Exclusions, Limitations, and Sub-Limits

Policies often exclude damage to or provide sub-limits of liability for personal property “primarily used for business purposes.” But certain business property, like home computers, can become comingled with non-business property and may be multipurpose, especially as more people work from home. Some exclusions focus on the property’s current use, while others encompass property “ever used” for business purposes.18

Most policies contain sub-limits for certain categories of personal property, such as collectibles, including baseball cards, stamps, and comic books. For these items, it may be necessary to obtain a separate personal articles or collections policy or rider to ensure adequate protection. Other items for which special sub-limits may apply include guns, furs, jewelry, watches, precious stones, stamps, coins, medals, fine china, and wine bottles. Nearly all policies contain sub-limits for cash.19 Proving the presence and amount of burned up cash may be a challenge, although contemporaneous bank and ATM cash withdrawal records may help supply proof.

Compiling a Loss Inventory

Homeowners should carefully read their entire policy and all its riders and endorsements to ensure they are complying with its terms, are aware of all claim limitations and deadlines, and understand what is required of them when submitting and proving a personal property claim. Homeowners should not agree to a quick settlement simply to avoid the heartache and headache of compiling a lost property inventory. If the process seems too daunting, they should consider hiring a licensed, reputable, and competent public adjuster, usually on a negotiated “percentage of the paid claim” basis, perhaps with a monetary fee cap and/or excluding or limiting fee recovery for payments already or required to be made.20 A good public adjuster can save insureds a lot of time and stress.

Critically, under no circumstance should insureds attempt to pad their claim by including items they did not own or claiming that the destroyed property was of higher quality or grade than what they actually owned. A single false statement of fact, knowingly made with the intent to mislead the insurer, can void some or all of a claim and even lead to criminal prosecution.21 Conversely, an insurer must not mislead insureds or deprive them of their insurance benefits. Given the emotional toll of a disaster that destroys a home and its contents and the inherent difficulties of compiling and valuing/depreciating a houseful of personal property—including the inevitable errors and duplication that may find their way into a post-loss personal property inventory consisting of thousands of line items—mistakes should be expected during the inventory compilation process. However, such innocent errors should not supply grounds for voiding a claim or sustain allegations of fraud.22 Moreover, homeowner opinions as to perceived value, general condition (“slightly worn,” “like new”), and depreciation are not generally considered statements of fact sufficient to establish fraud.23

Various strategies can be used to create an inventory of destroyed personal property. Some insurers and public adjusters, as well as online resources, can supply blank form inventories grouping items by room (e.g., kitchen, dining room, primary bedroom, primary bathroom, etc.), or by grouping similar items (e.g., kitchen tools, pots and pans, kitchen appliances, sporting goods, men’s clothing, etc.), or by the nature of the goods (e.g., cooking implements, camping equipment, etc.)24. The more complete and accurate the inventory, the greater the chances of negotiating for and obtaining full compensation. Creating a spreadsheet can be useful,25 and inserting hyperlinks to online cost information can both simplify and expedite the claims process. Depending on the circumstances, some insurers may waive inventory and/or proof of loss requirements following discussion and negotiation, even up to the policy’s payment limits. Colorado’s Division of Insurance persuaded several insurers to do this following the Marshall Fire.

One common starting point is to draw a floorplan and work room-by-room through the home, recollecting from memory what was present and/or imagining walking around each room, looking in all its storage spaces (closets, drawers, and cabinets), and recording the contents from every vantage point. Homeowners should take their time and take breaks to limit burnout—recreating a home inventory is a highly emotional, stressful, tedious, and draining experience. It can be helpful to start with the largest or highest value items in each room, because they’re often the easiest to remember, and to group similar items together.

Home photos and videos, including those taken by relatives during holiday, birthday, or other celebrations, may capture scenes in a home that can be a great help. Although often traumatizing, sifting through the ashes or soaked remnants of a home after a fire or flood may reveal lost property fragments, and photos of these pieces may offer additional proof of loss. Also helpful are hard copies of receipts (if they survived), online and cloud-stored electronic copies of receipts, and electronic purchase record compilations. If the homeowner frequently shopped at the same store for specialty items like clothing, or sports, ski, scuba, and camping equipment, the vendor may be able to retrieve purchase records by name or credit card number.26 Simply walking through hardware, houseware, clothing, department, and sporting goods store aisles can help jog memories, and so may perusing Amazon, Best Buy, and Wal-Mart websites. A bridal registry scanner may help with compiling prices for destroyed property.

Establishing ACV and Replacement Costs

Homeowners should ask the insurer for a copy of its depreciation schedule, which it is statutorily required to produce.27 There is no generally accepted or legally enforceable depreciation schedule.28 After receipt of an ACV payment, the homeowner should then provide the insurer proof of the cost of fully replacing the item and seek reimbursement of the item’s actual replacement cost, less any ACV previously paid. When establishing unconditional replacement cost values or ACV before an item is replaced, proof issues often emerge. Replacement cost is usually measured as of the date of the loss, but values pegged in rough proximity to that date will often suffice.29 There is no one correct depreciation formula when calculating ACV because such measures are subject to debate and are dependent on the item’s age, condition, and current availability (though many insurers rely on age alone). Depreciating fine arts and vintage and precious gems and metal jewelry may not be justified because their value often appreciates over time.30 Critically, Colorado has long recognized that property owners may testify to the value of their own property, both real and personal, with few limitations.31 Accordingly, courts have held that owners should be allowed to testify to their personal property’s depreciated value.32

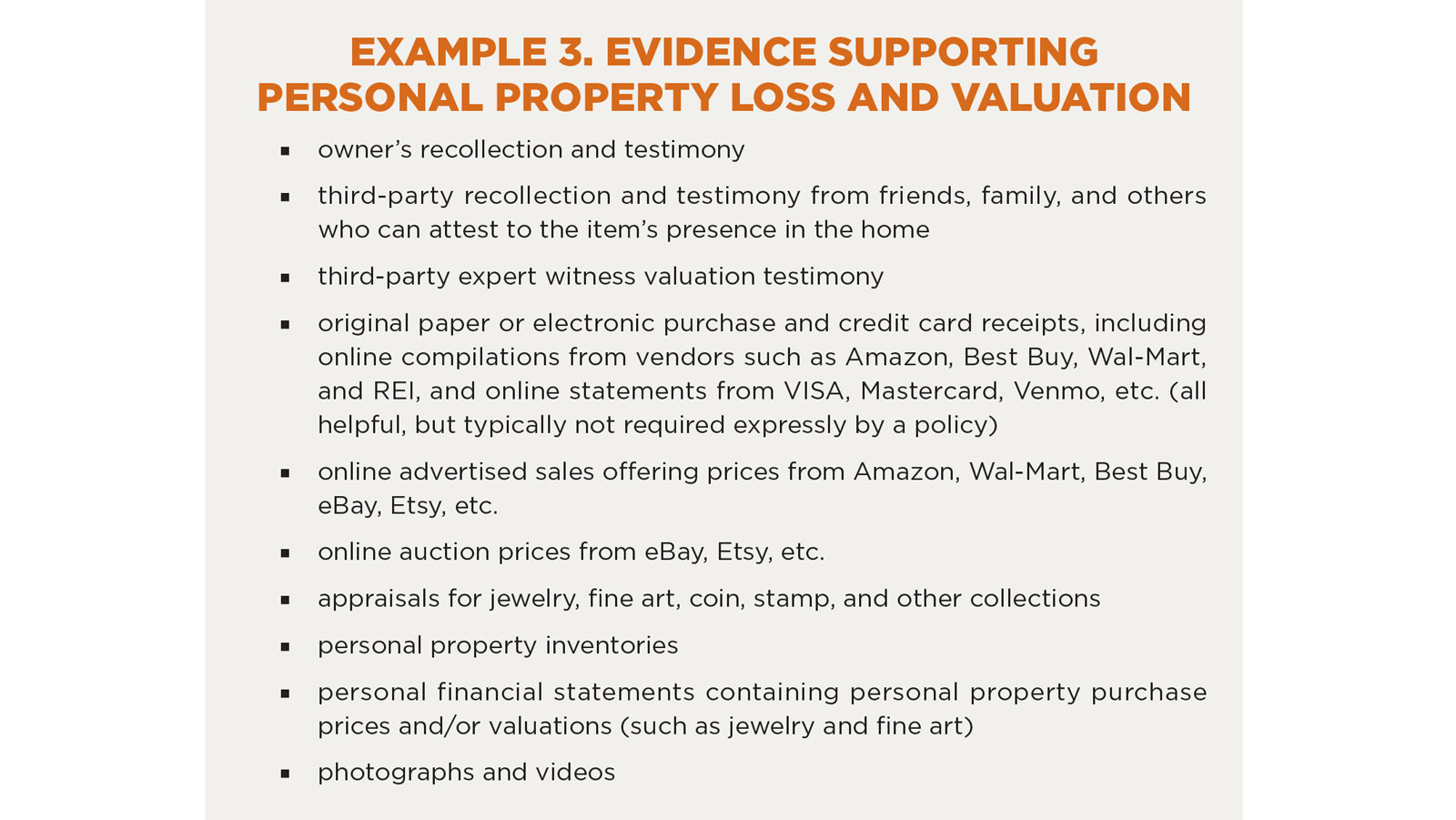

Colorado has allowed personal property owners to prepare a list of their lost property from memory (particularly if the property is completely destroyed), to use that list while testifying, and to provide details about the property’s original cost, how long they used it, and its condition when destroyed.33 Pricing should be based on identical property or similar items of like kind and quality. Where an item is no longer available, functionally and/or aesthetically similar items may offer a fair approximation. Example 3 shows the types of evidence that a homeowner might use to prove an item was present when the house was destroyed, as well as the item’s replacement cost and/or depreciated value (ACV).

An interesting question is whether homeowners can rely on offering prices rather than actual sales prices when valuing their property for unconditional replacement cost or ACV purposes.34 In 1976, People v. Codding rejected as hearsay the admission of price tag evidence to establish merchandise’s value in a criminal theft prosecution and also declined to apply the business record hearsay exception due to lack of foundation for the price tag preparation method.35 Codding’s holding was later abrogated by a statute expressly declaring price tag evidence non-hearsay and admissible in theft cases.36 More recently, in 1996, the Colorado Court of Appeals affirmed a trial court’s exercise of discretion in admitting price quotations for various items contained in a letter and a second set of quotations transmitted by fax cover sheet under Colo.R.Evid. 803(6), the business records exception to the hearsay rule.37 The court stated:

[W]hen information is provided as a part of a business relationship between a business and outsiders, the records may be admissible. This is particularly so if the information was provided at the request of the business and the document was of a type typically relied upon by that business in making decisions.38

The court added that “the documents themselves reveal that such were prepared as part of a regularly conducted business activity . . . namely, the sale of service and products and relate to a business activity . . . the purchase of such items.”39

Several courts outside Colorado allow price tags as evidence of value under the business records hearsay exception, reasoning that retail stores and consumers rely on price tags when buying and selling merchandise.40 Given the broad latitude Colorado courts afford property owners to express opinions on their property’s value, our courts may conclude that offering prices help support owners’ valuation opinions. Although the offering price itself might be inadmissible hearsay, the author has found no Colorado case so holding in the context of insurance claim personal property valuations. The use of and reliance on advertised personal property prices by Colorado insureds and their public adjusters—and insurers and their in-house adjusters—during the claims adjustment process is not uncommon.41

Colorado Insurance Regulations Concerning Personal Property Claim Payments

Colorado Code of Regulation 702-5:5-1-14 provides that a homeowner insurer

shall make a decision on claims and/or pay benefits under the policy within sixty (60) days after receipt of a valid and complete claim unless there is a reasonable dispute between the parties concerning such claim, and provided the insured has complied with the terms and conditions of the policy of insurance.

An insurer faces monetary penalties for violations. The regulation defines the terms “valid and complete claim” and “reasonable dispute” rather broadly, which leaves much room for debate whether the insurer has met its obligations.

Steps to Take Before Loss

Creating a home inventory before a loss occurs is rarely done, but it can pay enormous dividends and save the homeowner much work and stress later. Videos of every piece of personal property accompanied by an audio narration of what is being shown, brand and model names, vendors or stores from which the items were purchased, and dates and estimated or actual dollar amounts of purchase are incredibly useful. Photographs of individual items can supply detail a video may miss. Pull things out of every drawer, closet, and cabinet and spread them out for more complete and accurate images. Store offsite or make electronic copies of valuable papers such as passports, car and home titles, diplomas and certificates, and vaccination and birth records.

It is important and efficient to maintain electronic copies of all inventories, receipts, photos, and videos in multiple places, such as in the cloud, in a safety deposit box, and in a fire-resistant safe or box.42 The inventory itself should include an item’s brand and model/style name, its age, its quantity, its purchase price (including whether purchased new or used), and its condition—be as detailed as possible. And update your inventory and supporting digital imagery at least every two or three years.

Conclusion

The trauma and tedium of completing a personal property inventory with valuations is often a necessary evil that follows the loss of a home in a natural disaster. These stresses can be mitigated by taking steps to create and update a detailed inventory before the loss occurs. Courts and many insurers tend to give the benefit of the doubt to homeowners in construing homeowner policies and evaluating personal property loss claims following such disasters. State statutes, insurance regulators’ moral suasion, and the desire of insurers to maintain the goodwill of existing and future insureds can lead to personal property loss payouts without the necessity of formal proof of loss and property valuations. Whenever possible and if affordable, every insured should consider buying unconditional replacement cost insurance that will pay the cost of replacing destroyed property with the same or comparable new property without insureds first having to pay for such replacement out of their own pocket.

Related Topics

Notes

1. Colorado Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, “DR4634 Marshall Fire and Straight Line Winds,” https://mars.colorado.gov/MarshallFire.

2. House fires and wildfires can range from 400 degrees to 9,000 degrees Fahrenheit depending on fuel source and oxygen content. See Firefighter Insider, “What Is the Temperature of Fire? How Hot Does It Get?,” https://firefighterinsider.com/temperature-of-fire.

3. As a large Colorado homeowners insurer notes, “[R]enters, homeowners and condo insurance policies typically include coverage for the contents of your home. This coverage is sometimes known as ‘contents insurance,’ but is usually described in most insurance policies as personal property coverage.” Allstate, “What Is Contents Insurance?,” https://www.allstate.com/resources/what-is-contents-insurance.

4. CRS § 10-4-110.8(11)(a). On June 2, 2022, Governor Polis signed into law House Bill 22-1111, which raised the minimum percentage of personal property limits owed by insurers for total losses by a wildfire disaster at owner-occupied residences to 65%, without requiring a written contents inventory. CRS § 10-4-110.8(14).

5. See Consumer Advisory: Boulder County Fires—Improving Policyholders’ Experiences, DORA: Division of Insurance (Mar. 14, 2022), https://doi.colorado.gov/news-releases-consumer-advisories/consumer-advisory-boulder-county-fires-improving-policyholders. Insurance Commissioner Mike Conway argued to insurers that they needed to “get out of their own way” because based on past claims experience, they were ultimately going to pay this higher percentage anyway; he said he would publish the names of insurers who refused to get on board. Other states may well follow this creative and groundbreaking approach.

6. See United States v. Ostrom, 80 F.Appx. 67, 71 (10th Cir. 2003) (pursuant to policy’s fraud clause, a misrepresentation concerning part of claim relieves the insurer of its obligation to pay any portion of the claim, citing cases).

7. See Karabinos, “Detecting Contents Fraud: A Practical Approach to Examining an Insured’s Loss Inventory List” (Apr. 30, 2018), https://www.mondaq.com/unitedstates/insurance-laws-and-products/696872/detecting-contents-fraud-a-practical-approach-to-examining-an-insured39s-loss-inventory-list (originally published in CLM Magazine).

8. Cf. Gulf Ins. Co. v. Carroll, 330 S.W.2d 227, 233 (Tex.App. 1959), followed in Harper v. Penn Mut. Fire Ins. Co. of West Chester, Pa., 199 F.Supp. 663, 666 (D.C.Va. 1961) (“If depreciation is to be deducted from the cost of new materials, it would frequently make the sum insufficient to complete the repairs, thereby resulting in the building being only partially completed.”).

9. Financing options might include insureds tapping into their savings, borrowing money, or using payments under other policy coverages as essentially loans to themselves.

10. Buckley Towers Condo., Inc. v. QBE Ins. Corp., 395 F.Appx. 659, 663 (11th Cir. 2010) (applying Florida law).

11. Schirle, “Measuring Damages in a Megaloss if ‘Like Kind and Quality’ Does Not Exist,” 36 The Brief 31, 32 (Fall 2006) (ABA Tort Trial and Insurance Practice Section).

12. Id. at 33. Cf. Dupre v. Allstate Ins. Co., 62 P.3d 1024 (Colo.App. 2002) (court rejected insurer’s argument that “equivalent construction for similar use” limits dwelling replacement cost coverage to the “reproduction cost.” Citing the plain meaning of the words, the court concluded that since the dictionary definitions of both “equivalent” and “use” contemplated “functionality,” the phrase “equivalent construction for similar use” includes maintaining the property’s function before loss.)

13. Schirle, supra note 11 at 33. The “functional loss restriction” is “designed to be used when replacement of the personal property in question with substantially identical property is either impossible or unnecessary, usually as a result of technological change.” Id. (quoting 2 International Risk Management Institute, Commercial Property Insurance, ISO Forms and Endorsements, VI.F.48 (2003)).

14. See Epps, “Adjusting Residential House Fires,” IRMI Expert Commentary (Oct. 2004), https://www.irmi.com/articles/expert-commentary/adjusting-residential-house-fires.

15. See, e.g., W. Fire Ins. Co. v. First Presbyterian Church, 437 P.2d 52 (Colo. 1968) (where gasoline vapors penetrated church foundation and accumulated, rendering building uninhabitable, the property suffered a “direct, physical loss”). See also Henderson et al., “Survey of COVID-19 Insurance—Part 1: Coverage for Business Income Interruptions,” 49 Colo. Law. 58–60 (Aug./Sept. 2020), https://cl.cobar.org/features/survey-of-covid-19-insurance-issues-part-1 (discussing what constitutes “direct physical loss”).

16. See United Policyholders, “Smoke and Ash Damage from a Wildfire,” https://uphelp.org/claim-guidance-publications/smoke-and-ash-damage-from-a-wildfire.

17. Haught v. State Farm General Ins. Co., 2009 WL 2235937, at *10 (E.D.Mo. 2009) (inventory created factual issue whether insured’s personal property was either totally damaged or only partially damaged by fire).

18. See Pepper v. Allstate Ins. Co., 799 N.Y.S.2d 292, 295 (N.Y.App.Div. 2005) (phrase “used or intended for use in a business” reasonably meant only property “currently being used for business purposes”). Cf. Warren v. Farmers Alliance Mut. Ins. Co., 501 P.2d 135 (Colo.App. 1972) (insured’s fiberglass mold’s destruction while it was located on contractor’s premises was not excluded as “business property while away from the described premises” because insured’s main income was from the oil business, and he manufactured fiberglass sports car bodies only as a hobby).

19. Cf. Cotlar v. Gulf Ins. Co., 318 So.2d 923, 926-27 (4th Ct.App.La. 1975) (policy limitation intended to exclude coverage of property consisting of money did not apply to the insured’s collection of Mardis Gras souvenir doubloons).

20. See CRS § 10-2-417 (describing public adjuster licensing, financial responsibility, and standards of conduct); -417(6)(a) (public adjuster must serve the client with “objectivity and loyalty” in a manner that will “best serve the insured’s insurance claim needs and interests”).

21. See, e.g., CRS §§ 10-1-128 (fraudulent insurance acts); 18-5-211 (criminal code definition of insurance fraud).

22. Cf. Transp. Ins. Co. v. Hamilton, 316 F.2d 294, 296–97 (10th Cir. 1963) (while knowing and willful over-estimated values made with the intent to deceive insurers may void coverage, insureds may present inaccurate proofs due to faulty memory, inadvertence, wildly divergent valuations views, and unavailability of evidence without acting with fraudulent intent).

23. Generally, opinions are not considered factual representations sufficient to support a fraud claim. See, e.g., Knight v. Cantrell, 390 P.2d 948, 951 (Colo. 1964) (statement that dwelling was a “good house” was an opinion and could not support a misrepresentation claim).

24. See, e.g., United Policyholders, “Household Inventory Sample Spreadsheet,” https://uphelp.org/claim-guidance-publications/household-inventory-sample-spreadsheet.

25. Consider spreadsheet column headings for: Line Number, Room Location, Item Description, Vendor/Brand Name, Purchase Date, Purchased New or Used, Item’s Age on Date of Loss, Quantity, Purchase Price, Depreciated Value/ACV (if required), Replacement Cost (with embedded hyperlink to site for same or similar item with pricing), Sales or Other Tax, Shipping/Installation/Other Acquisition Costs, Total (Extended) Replacement Cost [summing values], and Comments. Don’t forget to include compensable cash and securities.

In some contexts, Colorado recognizes “acquisition costs” as a component of personal property valuation. See, e.g., 5 Division of Property Taxation, Colorado Department of Local Affairs, Assessor’s Reference Library: Personal Property Valuation Manual § 3.4 (1989, rev. vol. 2002) (original personal property installed means the cost as “the amount that was paid for the personal property when it was new,” and includes “the purchase price of the item, freight to the point of use, applicable sales/use tax and any installation charges necessary to ready the property for use . . . .,” as quoted in Xerox Corp. v. Board of Cnty. Comm’rs, Arapahoe Cnty., 87 P.3d 189, 192 (Colo.App. 2003) (emphasis added). The purchase of some household items, including some computer, home alarm, and audio-visual systems and equipment, requires paying initial setup, calibration, and programming fees, all of which may qualify as acquisition costs.

26. Moreover, if the insured owned 20 shirts purchased at the same store, the average value of similar shirts sold at that store may supply a reasonable estimate of the shirts’ aggregate replacement cost.

27. CRS § 10-4-110.8(11)(b) (insurer must make available its methodology for determining depreciation).

28. Depreciation guides are available. See e.g., The Claim Pages Depreciation Guide (Personal Property), https://www.claimspages.com/documents/docs/2001D.pdf and https://uphelp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Depreciation_CP-2.pdf. See also United Policyholders, Depreciation Basics, https://uphelp.org/claim-guidance-publications/depreciation-basics, and Personal Property Depreciation, https://uphelp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/UP-Depreciation-Schedule-1.pdf. The author is not aware of any insurers who maintain internal depreciation guides that they expressly incorporate by reference into their policies with the aim of binding their insureds.

29. If one links an inventory item to an online sales price and that price is reduced over time, the original price may still be the more accurate price because it was set closer to the date of loss and because seasonal sale prices are typically transitory.

30. People v. Ensley, 477 N.E.2d 760, 761

(Ill.App.Ct. 1985) (in appeal challenging amount of restitution following theft conviction, court observed that various jewelry constituted property that would normally appreciate in value). Other kinds of property may not be subject to any depreciation. See People v. Rednour, 665 N.E.2d 888, 889 (Ill.App.Ct.Dist. 1996) (a safe “is not subject to substantial mechanical deterioration. Therefore, its life span is indefinite.”).

31. See generally, Maguire, “An Owner’s Right to Testify to Value,” 25 Colo. Law. 77 (Nov. 1996) (property owner may testify to property’s value if testimony is not based on “improper considerations”); Annot., Dransfield, “Admissibility of Opinion of Nonexpert Owner as to Value of Chattel,” 37 A.L.R.2d 967 (1954, 2022 Supp.). See also Montgomery v. Tufford, 437 P.2d 36, 40 (Colo. 1968) (where owner prepared a lost personal property list and estimate of values from memory before trial, owner was competent to testify as to values over objection that the valuation was speculation and conjecture). See also Goetz v. Sec. Indus. Bank, 508 P.2d 410, 412 (Colo.App. 1973) (where plaintiff had a “precise recollection of the number of items which were taken by the bank and stated the range, in his opinion, of their values,” trial court properly used plaintiff’s lower valuation for each tool and excluded any item the plaintiff wasn’t certain was in the truck); Keller-Loup Const. Co. v. Gerstner, 476 P.2d 272, 274 (Colo.App. 1970) (tenant was competent to testify to itemization of destroyed personal property, including value estimates so as to allow trial court to determine property’s value at time of loss); Grange Mut. Fire Ins. Co. v. Golden Gas Co., 298 P.2d 950, 955 (Colo. 1956) (allowing owner testimony as to value of personal property destroyed by fire; “The record is gorged like an overfed gourmet with evidence of plaintiffs’ reconstructed, itemized personal property losses. These were proved over defendant’s objection in a reasonable manner since the property in question was destroyed and was unavailable for valuation.”); Colo. Midland. Ry. Co. v. Snider, 88 P. 453, 454–55 (Colo. 1906) (household goods’ value may be shown in connection with other things to enable the jury to infer the goods’ value when they were destroyed; court found that the destroyed articles’ cost, how long they had been in use, and their condition when destroyed was competent evidence of their value). Cf. In re Marriage of Plummer, 709 P.2d 1388, 1389–90 (Colo.App. 1985) (owner must be shown to have “the means to form an intelligent opinion, derived from an adequate knowledge of the nature, kind and value of the property in controversy”; husband precluded from testifying to value of wife’s separate property); however, the scope and validity of this dicta was questioned in Vista Resorts, Inc. v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 117 P.3d 60, 69 (Colo.App. 2004).

32. See, e.g., Denver Urb. Renewal Auth. v. Berglund-Cherne Co., 568 P.2d 478, 483 (Colo. 1977) (owners may testify to property’s depreciated value).

33. See Colo. Midland Ry. Co. v. Snider, 88 P. 453 (Colo. 1906); Grange Mut. Fire Ins. Co. v. Golden Gas Co., 298 P.2d 950 (Colo. 1956).

34. Real estate—as opposed to personal property—valuation experts typically rely on actual comparable sales prices rather than offering/listing prices when determining real property fair market value. Cf. Bennett v. Price, 692 P.2d 1138, 1140 (Colo.App. 1984) (real estate listing prices may tend to be inflated and may overstate the property value; the better reasoned rule is that such evidence is speculative and unreliable).

35. People v. Codding, 551 P.2d 192, 193 (Colo. 1976).

36. CRS § 18-4-414(1)–(2) provides that

“[e]vidence offered to prove retail value may include, but shall not be limited to, affixed labels and tags, signs, shelf tags, and notices,” and “[h]earsay evidence shall not be excluded in determining the value of the thing involved.” Thus, “[b]y enacting § 18-4-414, the General Assembly intended to reflect the fact that the price tag on an item presumptively is the means by which sellers designate an item’s retail value. Ordinarily, customers do not bargain over the price of retail goods.” People v. Schmidt, 928 P.2d 805, 807 (Colo.App. 1996). As Schmidt noted, “the price tags now speak for themselves.” Id. at 808. Whether a Colorado court would find CRS § 8-4-414’s legislative recognition of a “price tag” exception to the hearsay rule persuasive in recognizing a similar exception under CRE 803(6), the business records exception, in the context of an insurance personal property loss claim, is an open question. Cf. CRE 803(17) (market quote exception to hearsay rule); CRE 807 (“residual” exception to hearsay rule if “equivalent circumstantial guarantees of trustworthiness” are present). Codding was decided in 1976 and, therefore, the effect of Rule 807, adopted in 1999, was not considered.

37. See Hauser v. Rose Health Care Sys., 857 P.2d 524, 530 (Colo.App. 1993).

38. Id.

39. Id. (citing with authority United States v. Grossman, 614 F.2d 295 (1st Cir. 1980) (approving admission of manufacturer’s price catalogue to establish retail prices under business records exception)).

40. State v. Odom, 393 S.E.2d 146, 151 (N.C.App. 1990); accord People v. Mikolajewski, 649 N.E.2d 499, 504 (Ill.App. 1995) (holding that price tags are self-authenticating due, in part, to “the day-to-day reliance by members of the public on their correctness and the unlikelihood of fabrication”); Robinson v. Commonwealth, 516 S.E.2d 475, 478–79 (Va. 1999) (recognizing a judicial hearsay exception for price tags, stating that “the inherent unreliability of hearsay is not present” where a buyer understands that the tagged price is what must be paid in order to purchase an item, and that “it would be unreasonable and unnecessary to require that in each case a merchant must send . . . personnel to establish the reliability of the information shown on a price tag affixed to an item that has been stolen.”).

41. Many insurers use the XactContents software program to compile and establish ACV and replacement cost values on homeowner inventory. This program’s pricing is extracted from “major national retailers,” https://www.verisk.com/insurance/products/xactcontents. Such software has been criticized because it may rely on outdated historical data and/or irrelevant pricing from distant geographies or dissimilar socio-economic regions.

42. Items stored on-premises in “fire-rated” safes may still be destroyed in a fire. Many times, the contents are not burned but rather become subject to such high temperatures transmitted through the safe’s metal components that rare coins will melt and paper currency and valuable papers will turn brittle or be reduced to dust.