Rollover Equity Conundrum in Transactions With Private Equity Funds

May/June 2025

Download This Article (.pdf)

This article explains the conflicting application of the partnership termination rules under IRS Revenue Ruling 99-6 and IRC § 708(b)(1) and the partnership continuation rules under IRC § 708(a) for sales of partnerships that include tax-deferred contributions in exchange for rollover equity. It also questions whether, in a conflict between the two sets of rules, tax treatment as a partnership continuation should trump characterization as a partnership termination. A version of this article first appeared in the January 6, 2025, issue of Tax Notes Federal, available at https://taxnotes.co/407EahY. It is reprinted here with permission.

In a business exit transaction involving the sale of a business to a private equity fund (PE buyer), it is common for the owners selling the business to implement partial exits. Partial exits involve selling a portion of the business for cash and contributing the remaining portion on a tax-deferred basis under Internal Revenue Code (IRC) § 721 to the PE buyer’s platform in exchange for rollover equity in either an existing or a newly formed partnership to be managed (and controlled) by the PE buyer.1 This allows sellers to get tax deferral on the contributed portion of their business interests and a second bite of the apple upon a future exit by the PE buyer for, presumably, an appreciated equity interest.

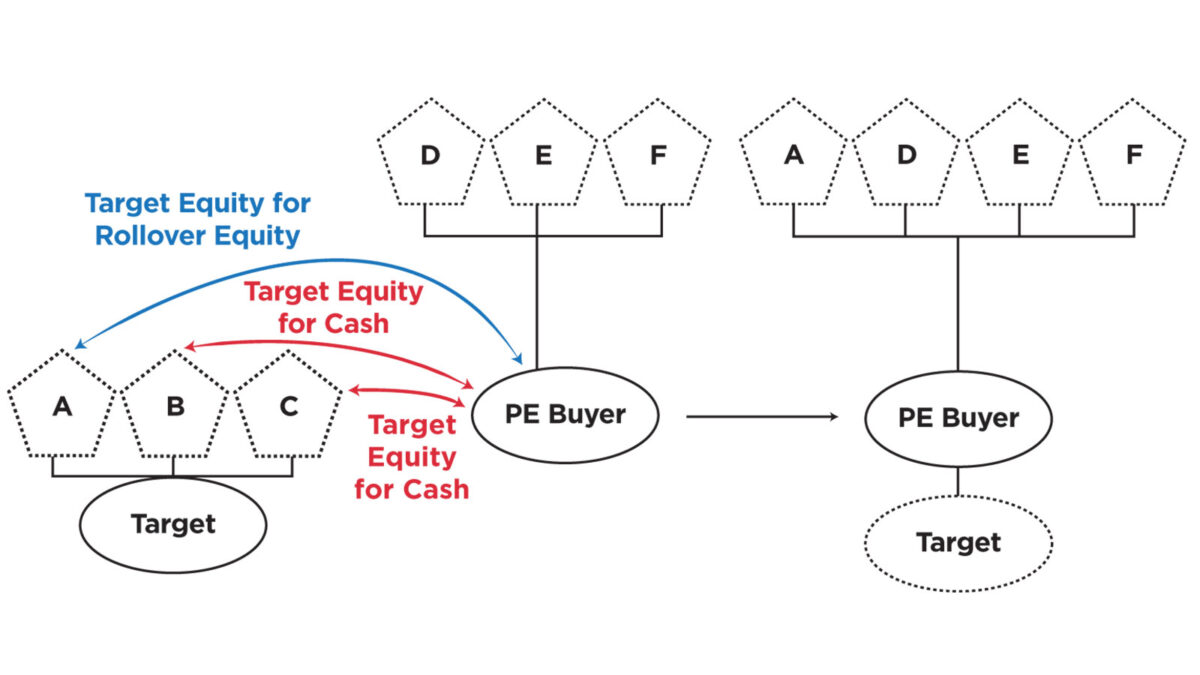

If the business entity (target) is classified as a partnership, upon the selling members’ contribution and sale of their partnership interests to the PE buyer, the target will generally default to disregarded entity status under Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-3. Disregarded entity treatment results because the target will be owned by a single member, the PE buyer’s acquisition vehicle. Figure 1 illustrates a common acquisition transaction structure involving the target in which one of three owners receives rollover equity in the PE buyer’s platform as part of the purchase consideration.

As a general rule, the contribution of a target’s equity interests and the purchase of the remaining interests by a PE buyer causes the target to terminate as a partnership for federal income tax purposes. Under existing tax rules, IRS Revenue Ruling 99-6, 1999-1 C.B. 432 should govern partnership terminations for the sale of a target to a PE buyer, which causes the target to become disregarded. However, the ruling does not address situations in which the business of a target is continued by more than one of its partners. Section 708(b) and the corresponding regulations describe various scenarios (and their applicable tax outcomes) resulting in partnership continuations that are seemingly more aligned with commonly implemented private equity-rollover transactions.

This article discusses the conundrum around the conflicting application of the partnership termination rules under Revenue Ruling 99-6 and § 708(b)(1) (in light of the repeal of the technical termination rules)2 and the partnership continuation rules under § 708(a) for sales of partnerships that include tax-deferred contributions in exchange for rollover equity. It also explores the step transaction doctrine and substance-over-form principles to determine, in the case of a potential conflict between the two rules (or overlap), whether tax treatment as a partnership continuation should trump characterization as a partnership termination.

IRS Revenue Ruling 99-6

Revenue Ruling 99-6 provides the applicable guidelines for situations in which partnership interests are transferred and the partnership converts to a disregarded entity. The ruling sets forth the federal income tax consequences for the termination of a limited liability company (LLC) classified as a partnership under Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-3 when one party purchases all the LLC interests thereby causing the partnership to terminate under § 708(b). The ruling discusses two scenarios, both of which result in a partnership termination. Because the business is continued after the sale of the interests by one owner but no entity classification election is made for the LLC, the business defaults to a disregarded entity status upon termination of the partnership.

The ruling’s first scenario, situation 1, involves partnership AB, owned by two partners, A and B. A sells her entire interest to B. Upon termination of the partnership, A’s sale of her interest will be treated as a sale of partnership interest. Thus, A will recognize gain or loss under § 741, and the gain or loss will be capital gain or loss. The gain or loss will be subject to § 751(a), which may reclassify all or a portion of the gain or loss as ordinary for ordinary income items such as depreciation recapture, accounts receivables, or inventory items.3

From B’s perspective, the transaction is treated as a deemed liquidation of partnership AB, a distribution of all the assets to A and B, and a direct purchase of A’s assets by B.4 B’s basis in the assets acquired from A will be equal to the purchase price paid by B under § 1012. The holding period for those assets will begin on the day following the sale. Regarding the assets attributable to B through its interest in AB, upon a deemed distribution of the assets to B, B will recognize gain or loss under § 731(a), its basis in the assets will be determined under § 732(b), and B’s holding period in the assets will include AB’s holding period except for purposes of § 735(a)(2). In accordance with this outcome, B will have a split basis in the assets determined partially under § 1012 and partially under § 732. B’s §§ 167 and 168 cost recovery and § 197 deductions will be based on a presumably higher cost basis of that portion of the assets deemed purchased from A. B’s cost recovery will be subject to the anti-churning rules of § 197(f)(9)(A)5 (if applicable), while B’s cost recovery and amortization deductions attributable to the assets held by B in the AB partnership will continue based on the transferred basis under § 732.

Situation 2 involves a partnership, CD, owned by partners C and D in which both C and D sell their interests to a third party, E. Under this scenario, C and D would report gain or loss resulting from the sale of their partnership interest under § 741. E will be deemed to acquire assets from C and D following a liquidating distribution from CD. Thus, E’s basis in the assets will be equal to the purchase price under § 1012, and its holding period in the assets will begin the day after the sale.

Because Revenue Ruling 99-6 appears to be limited to situations that involve the complete termination of a partnership under § 708(b)(1)(A), it does not address situations in which the partnership is continued under § 708(a). Likewise, the ruling does not address situations in which a portion of a partnership is contributed on a tax-deferred basis to the buyer’s partnership. It follows that besides the tax consequences discussed in the ruling, there may be other implications for partnership transactions and planning considerations arising from this factual modification. These considerations include the assumption of liabilities, basis issues, tracking of interests in assets, anti-churning considerations, built-in gain and mixing bowl issues,6 as well as partnership continuation issues.

Partnership Continuation Under Section 708

Section 708 was enacted in 1954 and intended to address inconsistent case law that dealt with partnership terminations under local law based on the dissolution of a partnership in the case of a partner’s death and termination of a partnership occurring after the winding up of its affairs.7 By decoupling state laws from federal income tax rules,8 § 708 provides that a partnership continues for tax purposes if the business is continued by the partnership without regard to state law consequences. Section 708(a) provides that “an existing partnership shall be considered as continuing if it is not terminated.” Section 708(b)(1) provides that “for purposes of subsection (a), a partnership shall be considered as terminated only if no part of any business, financial operation, or venture of the partnership continues to be carried on by any of its partners in a partnership.”9 The regulations also provide that a partnership “shall terminate when the operations of the partnership are discontinued and no part of any business, financial operation, or venture of the partnership continues to be carried on by any of its partners in a partnership”10 (emphasis added).

The regulations provide an example of a partnership termination in accordance with a sale as opposed to a dissolution:

On November 20, 1956, A and B, each of whom is a 20-percent partner in partnership ABC, sell their interests to C, who is a 60-percent partner. Since the business is no longer carried on by any of its partners in a partnership, the ABC partnership is terminated as of November 20, 1956. However, where partners DEF agree on April 30, 1957, to dissolve their partnership, but carry on the business through a winding up period ending September 30, 1957, when all remaining assets, consisting only of cash, are distributed to the partners, the partnership does not terminate because of cessation of business until September 30, 1957.11

This example distinguishes a termination in accordance with a sale of partnership interests in which the business is no longer continued by the partnership from a dissolution under state law. In the case of the sale of partnership interests, the business is no longer continued by the partnership but is instead operated by one of the historic partners (individual C). Under those facts, the partnership is considered terminated as of November 20, 1956, because the historic business is not carried on in partnership form. This fact pattern is similar to Revenue Ruling 99-6 in which none of the historic partners continue to own and operate the business in partnership form. In comparison, when the partners of partnership DEF dissolve the entity under state law, the partnership will be considered terminated on September 30, 1957, once all activity of the partnership ceases and all assets are distributed to the partners. Likewise, if the partnership redeems all the partnership interests except for one remaining partner, it will be considered terminated only after all remaining partners are paid out.12

This distinction was analyzed by the IRS in Revenue Ruling 66-264, 1966-2 C.B. 248, in which three partners of a five-partner partnership purchased the partnership’s assets in a judicial sale. After the sale, the partnership’s historic business continued to operate through a new three-person partnership. Because the historic partners (three of the original five partners) continued the original partnership’s business in partnership form, the original partnership was not treated as terminating under § 708(b)(1)(A), and instead the new three-person partnership was deemed to be a continuation of the original partnership.

Example 1: Continuation of historic business in partnership form. Addison, Bailey, and Chester each own a one-third membership interest in Alamo LLC, a partnership for federal income tax purposes.

Upon formation:

- Addison contributed $1,000 cash;

- Bailey contributed tangible property with a book value of $1,000 and an adjusted tax basis of $0; and

- Chester contributed a building with a book value of $1,000 with an adjusted tax basis of $100.

Table 1. Example 1, Partnership Formation

| Alamo LLC | Assets | Adjusted Basis | Book Value |

| Addison (A) | Cash | $1,000 | $1,000 |

| Bailey (B) | Property | $0 | $1,000 |

| Chester (C) | Building | $100 | $1,000 |

| Total | $1,100 | $3,000 |

Current values:

- Alamo has a current enterprise value of $100,000, with no debt.

- Alamo’s assets have current values of $1,000 cash (basis of $1,000), tangible property valued at $1,000 (basis of $0), and a building valued at $98,000 (basis of $1,000, no improvements were made).

- Alamo is not operational (for example, no revenue generation). No partners received any distributions from Alamo, and no depreciation has been taken for the building (for example, the existing tax basis in the Alamo interests of each of the partners is the same as the initial tax basis upon formation).

Table 2. Example 1, Current Values

| Current Values of Assets | Adjusted Basis | Fair Market Value | FMV of LLC Interest | Adjusted Basis of LLC Interest |

| Cash | $1,000 | $1,000 | $33,333 (A) | $1,000 (A) |

| Property | $0 | $1,000 | $33,333 (B) | $0 (B) |

| Building | $100 | $98,000 | $33,333 (C) | $100 (C) |

| Total | $1,100 | $100,000 | $100,000 | N/A |

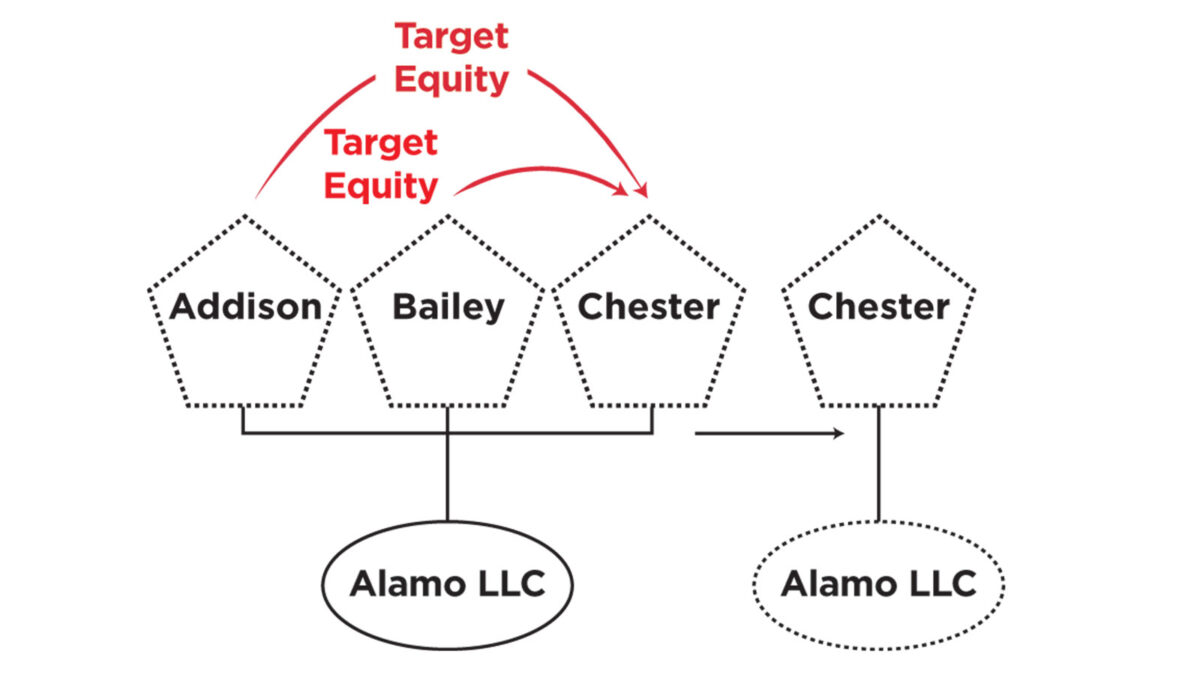

If Addison and Bailey decide to sell their membership interests in Alamo to Chester for $66,667, the transaction clearly fits within situation 1 so that Alamo terminates as a partnership for federal income tax purposes. Addison and Bailey are treated as each having sold their partnership interests for $33,333. Addison will recognize $32,333 of gain, and Bailey will recognize a gain of $33,333.13 From Chester’s perspective, Alamo is deemed to distribute its assets to the partners in liquidation, and immediately after the distributions, Chester is treated as purchasing a one-third undivided interest in the assets attributable to each of Addison’s and Bailey’s equity interests in Alamo. Chester will thus have a basis of $66,667 in the assets attributable to Addison and Bailey (basis of $666.67 cash, basis of $666.67 in personal property, and basis of $65,334 in the building). Chester will have a carryover basis for the assets attributable through his interest in Alamo.14 (See figure 2.)

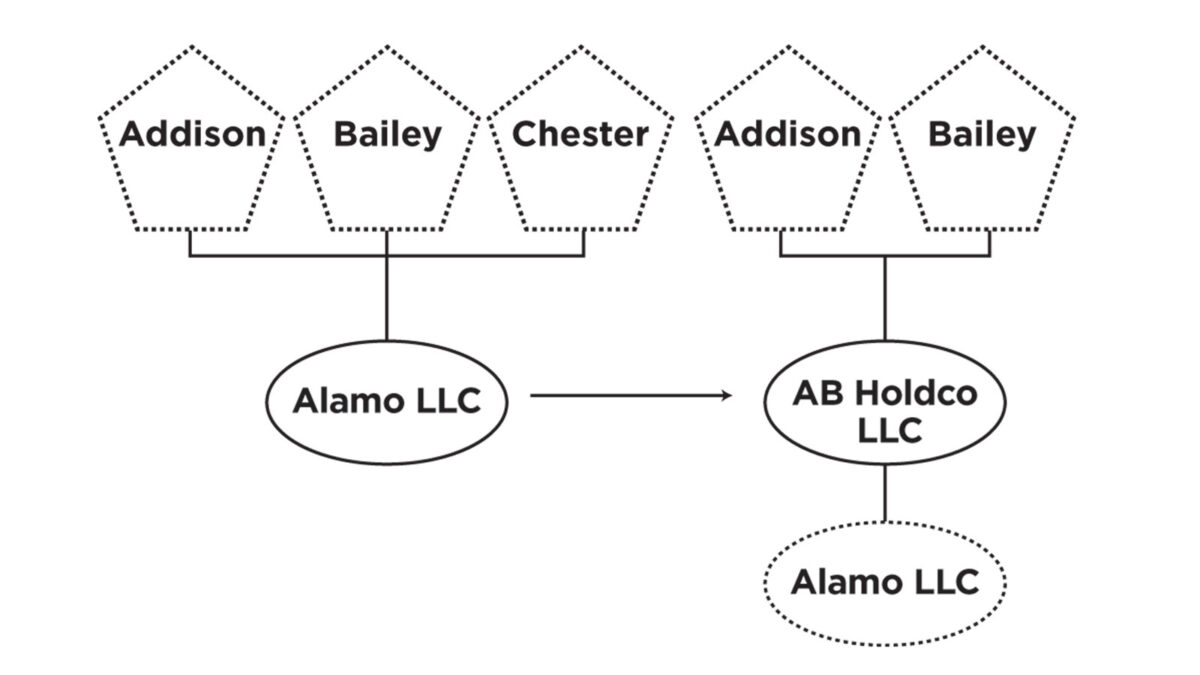

If Addison and Bailey instead decided to form a new partnership, AB Holdco LLC, to acquire all the assets of Alamo, the business conducted by AB Holdco would be treated as if AB Holdco were a continuation of Alamo, even though the business is now being conducted through a new juridical entity.15 This is known as “drop down continuation.”16 As a continuation of Alamo, the sale of Chester’s equity interest will be treated as a purchase and sale of a partnership interest.17 Chester will recognize gain of $33,233. If Alamo (and potentially AB Holdco) has a § 754 election in place,18 AB Holdco will adjust the basis in the assets attributable to Addison’s and Bailey’s respective interests to account for the $33,333 of cash used to purchase Chester’s interest.19 (See figure 3.)

What happens if Addison and Bailey sell all their membership interests in Alamo to a third party, but Chester contributes a portion of his equity in Alamo in exchange for equity in the buyer’s existing partnership? A sale transaction with a rollover equity component is often characterized as a transaction governed by Revenue Ruling 99-6, especially if the historic partnership terminates as a result of becoming a wholly owned subsidiary of a buyer or one of its affiliates. However, given the relatively simple facts described in the ruling and the panoply of rules described in § 708 and the corresponding regulations, it may be the case that most transactions involving rollover equity should be properly governed by the partnership continuation, merger, or division rules. How a transaction is described, particularly regarding the tax treatment and reporting requirements set forth in transaction documents, may have significant tax effects for all parties involved.

Merger Rules Under Section 708: Rollover Into Existing Partnership

In general, if there is a merger or consolidation of two or more partnerships, the rules under § 708(b)(2)(A) govern the tax treatment of the merger or consolidation. Neither the code nor regulations define what a “merger or consolidation” means for tax purposes; however, there is no express requirement that a state law merger is required. Under the existing partnership merger rules, the resulting (surviving) partnership is treated as the continuation of the merging partnership whose members own an interest in more than 50% in the capital and profits of the resulting partnership.20 The regulations provide an example of a partnership merger whereby a merger occurs between partnership AB and partnership CD on September 30.21 All partners report on a calendar year. Partnership AB is on a calendar year, while partnership CD has a fiscal year ending June 30. After the merger, the partners own interests in capital and profits as follows: A (30%), B (30%), C (20%), and D (20%). Because A and B own an interest of more than 50% (their collective interest equals 60%) in partnership ABCD, partnership ABCD is considered a continuation of partnership AB so that partnership ABCD will report on the calendar year.

The regulations describe two forms for a partnership merger: (1) assets-over form; and (2) assets-up form.22 The default form and most commonly adopted form of partnership merger is the assets-over form.23 In an assets-over merger, the terminating partnership is treated as having contributed all of its assets and liabilities to the resulting partnership in exchange for equity interests in the resulting partnership. Immediately after this deemed exchange, the terminating partnership liquidates and distributes its interests in the resulting partnership to its partners in complete liquidation.24 If cash is exchanged in the assets-over merger, gain or loss would be allocated to all partners of the terminating partnership because the partnership is deemed to receive cash in connection with the transfer of assets (and associated liabilities) to the resulting partnership. This outcome may be undesirable by the partners because some partners (that is, rollover partners) would be required to recognize proportionately more gain but receive proportionately less cash. Fortunately, the regulations contain a special rule that allows the parties to treat the selling partners as receiving cash in exchange for their partnership interests (the merger cash-out rule).25 By treating the cash-out partners as selling their partnership interests, this rule effectively allocates the cash proceeds only to those partners who are exiting.26

Example 2: Partnership mergers (assets-over).

Alamo LLC. Addison, Bailey, and Chester each own a one-third membership interest in Alamo, a partnership for federal income tax purposes.

Upon formation:

- Addison contributed $1,000 cash;

- Bailey contributed tangible property with a book value of $1,000 and an adjusted tax basis of $0; and

- Chester contributed a building with a book value of $1,000 with an adjusted tax basis of $100.

Alamo has a current enterprise value of $100,000, with no debt.

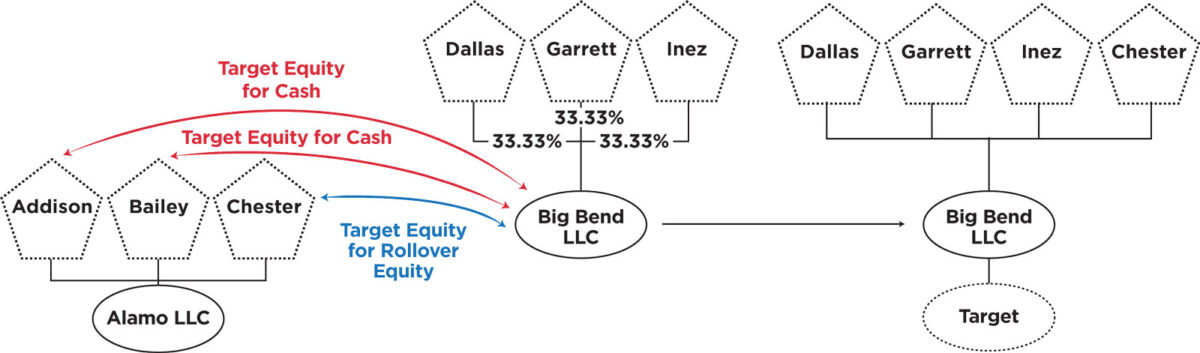

Big Bend LLC. Dallas, Garrett, and Inez each own a one-third membership interest in Big Bend, a partnership for federal income tax purposes.

Big Bend has a current enterprise value of $500,000.

Addison, Bailey, and Chester are considering a sale of their membership interests in Alamo to Big Bend. Addison and Bailey want to fully exit the business, while Chester is interested in continuing his ownership via rollover equity (no cash consideration) in Big Bend.

Similar to the resulting structure described in example 1, Big Bend will acquire 100% of the outstanding equity interests in Alamo, resulting in Alamo becoming a disregarded entity. Big Bend will have four equity holders: Chester, Dallas, Garrett, and Inez. (See figure 4.)

Under the application of partnership merger rules, the consolidation of Alamo and Big Bend would result in Big Bend becoming the surviving partnership because Dallas, Garrett, and Inez collectively own more than 50% of the capital and profits in the consolidated partnership.27 The purchase agreement includes language to comply with the merger cash-out rule to treat Addison and Bailey as selling their equity interests in Alamo to Big Bend. Because the parties agreed to adopt the merger cash-out rule, Addison and Bailey are each treated as selling their Alamo interests to Big Bend before the merger.28 Big Bend is treated as buying Addison’s and Bailey’s interests and succeeds to each former partner’s § 704(b) and (c) amounts. Next, Alamo is deemed to contribute its assets (and liabilities) attributable to Chester’s interest to Big Bend in exchange for an interest in Big Bend. Immediately after the deemed contribution, Alamo liquidates and distributes the Big Bend interest to Chester and distributes the remaining assets (and liabilities) to Big Bend in liquidation of the interest Big Bend just acquired in Alamo. Big Bend holds the assets distributed for Addison’s and Bailey’s interests with a basis equal to Big Bend’s basis in Addison’s and Bailey’s collective interests (FMV = $66,667) immediately before the distribution.29 Big Bend’s basis in the assets distributed for Addison’s and Bailey’s former equity interests becomes common basis that inures to the benefit of all the partners of Big Bend (including Chester) after the merger.30 Thus, to the extent the partners of Big Bend receive a tax benefit through incremental depreciation or amortization deductions, the rollover partner would also be entitled to its pro rata share of the tax benefits. The transfer of assets from Alamo to Big Bend generally starts the seven-year clock on the mixing bowl rules, so they should apply to the assets that Alamo was deemed to contribute to Big Bend. Any deemed contributed assets that have built-in gain would theoretically be tracked and allocated to Chester in the same manner that Alamo would have allocated the gain had the partnership sold the property for cash.31

If, in a transaction in which two or more partnerships become a single partnership, there is some component of partnership equity and cash that is used as purchase consideration, the rules described in § 708 suggest the transaction should be governed by the partnership merger rules. However, if one or more partnerships terminate by virtue of becoming disregarded entities, does the guidance in the ruling introduce uncertainty and potentially improper characterization of the transaction?

Transactions With Rollover Equity: Tax Treatment and Reporting

Partnership Termination or Partnership Merger?

Referring to the facts from example 2, Big Bend acquires Alamo with a combination of cash and rollover equity. Addison and Bailey sell all their membership interests in Alamo for an aggregate $66,667 of cash, and Chester sells his membership interests in Alamo for rollover equity (value of $33,333) from Big Bend. After closing, Alamo becomes wholly owned by Big Bend and defaults to disregarded entity status.

Because Alamo’s tax classification changes from partnership status to disregarded entity status as a result of the transaction, one may assume that Revenue Ruling 99-6 applies. But, if so, would situation 1 or situation 2 apply? Depending on how the transaction documents are drafted, either situation 1 or situation 2 could arguably apply to a rollover transaction, and each comes with its own set of wrinkles.

If situation 1 applies, Chester is first deemed to contribute his equity interests in Alamo to Big Bend in exchange for equity interests in Big Bend in a tax-free exchange under § 721. Next, Big Bend is treated as acquiring the remaining 66.67% equity interest in Alamo from Addison and Bailey, for a total of $66,667 of cash consideration in a taxable exchange under § 1001. From Big Bend’s perspective (and, ultimately, that of Dallas, Garrett, and Inez), Alamo is treated as distributing to all the partners (for example, Addison, Bailey, and Big Bend) the assets attributable to each of their interests, and then Big Bend is treated as purchasing those assets directly from Addison and Bailey.

Even though Revenue Ruling 99-6 does not specifically address tax-deferred exchanges, adherence to the ruling raises interesting issues that may often be overlooked by the parties. First, Big Bend will receive a basis step-up equal to $66,667 for the deemed purchased assets in Alamo attributable to Addison’s and Bailey’s equity interests. Any resulting depreciation or amortization deductions attributable to Big Bend’s basis step-up would generally be allocated among the partners based on the operative provisions of Big Bend’s governing documents. If we assume that the operating agreement of Big Bend allocates all tax items on a pro rata basis, then Chester would be allocated his pro rata share (5.6% = $33,333/$600,000) of any depreciation and amortization attributable to the basis step-up. If Dallas, Garrett, and Inez indirectly funded the acquisition of Addison’s and Bailey’s equity interest, their aggregate pro rata share of any depreciation or amortization resulting from the basis step-up is diluted from $66,667 to $62,963 because Chester also shares in the step-up. Further, the ruling treats a buyer as acquiring assets from the selling partners, so a buyer should carefully consider the potential effects of the anti-churning rules. If the anti-churning rules apply to a transaction, any incremental tax benefits may be significantly limited and would diminish the economic value of a basis step-up.

Second, because the situation 1 mechanics treat Alamo as having distributed to all the partners the assets attributable to their one-third partnership interests, the assets attributable to each partner’s interest would be a one-third interest in cash, a one-third interest in the tangible property, and a one-third interest in the building. Under the existing partnership rules, a partner who contributes built-in gain property is required to recognize gain when that same property is distributed to another partner within seven years.32 Thus, the deemed distribution that occurs in situation 1 may inadvertently accelerate a portion of any § 704(c) gain for the acquiring partner. If Chester had directly acquired the equity interests in Alamo from his other partners (Addison and Bailey) within seven years of Alamo’s initial capitalization, the deemed distribution in liquidation in situation 1 would cause Chester to recognize $600 of gain (attributable to the two-thirds of the $900 built-in gain in the building that is deemed distributed to Addison and Bailey).33

Because the deemed contribution occurs immediately before the sale, Big Bend presumably becomes a partner of Alamo—even if for a moment in time—for federal income tax purposes. When the deemed distribution of assets occurs before Big Bend’s acquisition from Addison and Bailey, does Big Bend recognize the same $600 of § 704(c) gain that is attributable to the underlying assets embedded in the Alamo interest that Chester contributed? Would Big Bend need to allocate that $600 of gain to Chester because he is the contributor of built-in gain property?

If situation 2 governs the transaction, Addison and Bailey are each treated as having sold their Alamo interests in accordance with § 741. From Big Bend’s perspective, Alamo is deemed to make a liquidating distribution of its assets to each of Addison, Bailey, and Chester. Immediately following the distribution, Big Bend is deemed to acquire, by purchase, all of Alamo’s assets for a combination of cash and rollover consideration. Big Bend will receive a basis step-up equal to $66,667 for the deemed purchased assets in Alamo attributable to Addison’s and Bailey’s equity interests. Like the outcome described under situation 1, Chester would generally benefit from incremental depreciation and amortization (subject to the anti-churning rules) attributable to the basis step-up by virtue of being a partner in Big Bend.34 However, before Big Bend’s acquisition, Alamo is deemed to distribute its assets to each of the partners in liquidation. Does the deemed distribution cause Chester to recognize $600 of his § 704(c) gain (attributable to two-thirds of the $900 built-in gain in the building that is deemed distributed to Addison and Bailey) even though he is not receiving any cash in the transaction? If this scenario applies, a buyer may prefer situation 2 to govern the transaction so that any income allocation (and resulting tax) on built-in gain remains with the rollover seller.

Finally, from a seller’s perspective, which would presumably include a rollover seller, situation 2 treats the selling parties as having sold their partnership interests. From Chester’s standpoint, is he treated as contributing his pro rata share of Alamo’s assets to Big Bend (which is how Big Bend would report the transaction), or is he treated as having contributed his partnership interest in exchange for equity interests in Big Bend? A literal reading of situation 2 suggests that Chester should be treated as having contributed his partnership interest to Big Bend to remain consistent with seller treatment in the ruling (similar to the construct in situation 1). However, the ruling itself does not describe any contributions in a tax-deferred exchange, which adds to the uncertainty of proper tax treatment and reporting.

If the ruling treats Chester as having contributed his partnership interest in a tax-deferred exchange, do the rules of § 704(c) require a look through to Chester’s contributed Alamo interest to ensure that he is allocated any remaining § 704(c) gain that is embedded in his Alamo interest? Big Bend will have carryover basis in the deemed contributed assets, but from Chester’s perspective, he contributed a portion of his Alamo partnership interests. If Alamo was a disregarded entity and its equity interests were partially contributed and partially sold, the partially contributed portion would be subject to § 704(c) and separately allocated to Chester. Here, Chester is partially contributing equity in an existing partnership. When Alamo’s partnership status terminates when it becomes a disregarded entity, Big Bend will presumably receive the portion of the assets (attributable to Chester’s contributed equity) and inherit the § 704(c) gain that was embedded at the asset level. Commentators have suggested any built-in gain for an asset should be tracked and allocated to the original contributing partner using a tracing method.35 Allocations of built-in gain in this manner mirror the built-in gain that would have been allocated by Alamo to its partners had Alamo sold the property for cash.

If the transaction were instead treated as a partnership merger, Big Bend would be treated as the surviving partnership, assuming Dallas, Garrett, and Inez collectively own more than 50% of the capital and profits in the consolidated partnership. The acquisition of Addison’s and Bailey’s equity interest will be treated as a purchase and sale of a partnership interest under § 741. If Alamo has a § 754 election in place in the year of the merger, Big Bend will receive a basis step-up of $66,667 in the underlying assets attributable to Addison’s and Bailey’s partnership interest. The resulting § 743(b) basis adjustment in the underlying assets attributable to Addison’s and Bailey’s partnership interest is not generally affected by the anti-churning rules.36 This basis step-up will be shared among Chester, Dallas, Garrett, and Inez (similar to the basis outcome in the ruling). For the deemed contributed assets by Alamo to Big Bend, Big Bend will take a carryover basis in the underlying assets. In an assets-over merger, when Alamo transfers its assets and liabilities to Big Bend, the interest in Big Bend is treated as successor § 704(c) property.37 When Alamo distributes the interest in Big Bend to Chester, it is unclear whether his tax basis and § 704(c) amounts in Big Bend are determined by taking into account his § 704(c) amounts in Alamo. A few approaches exist, but most commentators generally adopt the tracing approach described in the mixing bowl rules.38 Under the tracing approach, Chester is treated as receiving an interest in Big Bend that is traced back to the § 704(c) property (that is, the building) that he initially had contributed to Alamo.39 Any subsequent distributions of this built-in gain property are governed by the anti-deferral provisions (mixing bowl) of § 737.

Partnership Termination or Partnership Continuation?

What if the facts in example 2 changed so that Big Bend was a newly formed platform of the PE buyer so that Big Bend is initially a disregarded entity that becomes a partnership once the rollover equity is issued to Chester in connection with the transaction? The conundrum of whether this falls under situation 1 or situation 2 remains at the forefront, assuming the ruling even applies to this fact pattern.

In contrast, if the transaction is instead governed by the provisions of § 708, then Big Bend would likely be deemed to be a continuation of Alamo. If the transaction is characterized as a continuation, a full-year partnership tax return would be filed (using Big Bend’s legal entity name),40 and Addison and Bailey are each deemed to sell their partnership interests to Big Bend. Assuming Alamo and, presumably, Big Bend will have a § 754 election in effect, the PE buyer (equity owner of Big Bend) will benefit from a basis step-up in the amount of 66.667% of the assigned value (for example, $66,667) in each of the underlying assets of Alamo under § 743(b). The constructs of any basis adjustment under § 743(b) in this scenario are limited to the acquirer so that the tax benefit of a basis step-up is limited to the PE buyer (compared with the ruling in which it appears that Chester, as a rollover seller, would be entitled to share in the step-up). Because Big Bend will be treated as a continuation of Alamo, the transaction will typically result in a partnership revaluation event so that Alamo/Big Bend will book up the value of Alamo’s assets and the capital accounts of any continuing partners to fair value.41 The revaluation will cause any appreciation embedded in Chester’s continuing partnership interest to be separately tracked and allocated to Chester (upon certain events) as both “forward section 704(c) gain” (attributable to his initial contribution of the building with built-in gain) and “reverse section 704(c) gain” (attributable to any subsequent value accretion). Depending on the relevant tax provisions in Big Bend’s governing documents, allocations of income (to Chester) and deductions (to the other partners) may have timing considerations as well as economic effects for the parties.

Although it is common to see references to Revenue Ruling 99-6 in purchase agreements that involve similar facts described in the examples from this article, the ruling does not address a sale transaction with a rollover equity component. In fact, both situations described in the ruling contemplate a fully taxable transaction with no continuing or residual ownership by any of the selling partners. Rather, the scope of the ruling is limited to an actual partnership termination under § 708(b)(1)(A) whereby none of the partnership’s historic business activities are conducted by any of the partners in partnership form. The ruling does not contemplate a partnership continuation under § 708(a). The IRS has previously recognized the limitations of the ruling. According to a senior Treasury attorney quoted at a conference in the fall of 2022, the IRS has been working on this for a while and was considering revisiting the ruling, but could not say that guidance “would be out any time soon.”42 Likewise, the topic of partnership continuations in lieu of terminations and the overlap between § 708(b)(1) and the merger rules remains a hot topic for which the IRS has again acknowledged the need for guidance without any further comments.43

Substance Over Form and Step Transaction Doctrine

There appears to be no clear guidance on which intended tax treatment should govern a sale of partnership interests with tax-deferred contribution in exchange for rollover equity when the business of the partnership continues to be carried on by the PE buyer in the form of a new partnership.44 It may be treated as either (1) a partnership continuation under § 708(a) that may be subject to the application of the partnership merger rules, or (2) a partnership termination under the ruling and § 708(b), subject to further interpretation as to the proper application of situation 1 or situation 2. Given the lack of clarity on the issue, taxpayers are generally free to choose from the two alternatives and apply the more preferable option based on the tax consequences that may result, assuming no conflict exists between the selling and buying parties. However, given the self-serving interests of well-informed taxpayers to structure and influence tax results on the one hand and the general tax policy goals of neutrality, fairness, and efficiency on the other, the IRS should seek to clarify its position on the issue, including whether this type of transaction should be subject to § 708 continuation or merger rules, which would render the commonly cited ruling irrelevant in this context.

In analogous situations in which taxpayers engaged in a series of transactions characterized in a certain way to achieve an intended result, the IRS has historically decided those cases based on the general substance-over-form principles, which may be more specifically expressed by the step transaction doctrine. The substance-over-form doctrine is a common-law doctrine that states that “the incident of taxation depends on the substance rather than form of the transaction.”45 The IRS and the courts have applied this doctrine to recharacterize transactions and disallow certain tax benefits when the form of the transaction is different and does not properly reflect its actual substance, by looking “to the objective economic realities of a transaction rather than to the particular form the parties employed.”46 Thus, the substance-over-form doctrine allows the IRS and the courts to ignore technical form and look through the literal compliance with tax rules to the actual substance of the transaction.47

Regarding the example discussed above, under a literal interpretation of the existing rules, there may be a tendency to frame this transaction as a partnership termination under the ruling because the PE buyer’s acquisition of the target causes the target to convert from a partnership to a disregarded entity. Based on the general application of Revenue Ruling 99-6, which governs sales of partnerships resulting in partnership terminations, it is easy to apply the rules under the ruling and overlook that there is also a contribution under § 721 in exchange for rollover equity by one or more partners of the target. Because of the rollover component, it may be important to set the ruling aside and view the transaction as a whole. If one or more partners who were partners of the target continue to be partners of the PE buyer’s new partnership and the business of the target is continued by the PE buyer’s new partnership, does the economic reality point to the fact that there was never a termination of the old partnership, and the new partnership may in fact be the same old partnership?

It can be said that the IRS applied substance-over-form principles in its earlier rulings. In Revenue Ruling 66-264, discussed earlier, the IRS held that the partnership did not terminate, and the transaction was treated as a sale or liquidation of the partnership interests by the other two partners. This conclusion is supported by the substance-over-form principles—the old partnership had five partners; the new partnership had three of the old partners, who continued to operate the business; and the economic reality was that the partnership was continued by three partners and the interests of the two remaining partners were redeemed. In the context of the partnership merger rules, with the exception of the assets-up form of merger, the IRS has generally overlooked the actual form of the merger transactions in favor of the assets-over form48 because there can be multiple forms in which a merger may be implemented and some forms may cause complications in implementing other tax rules.49 This raises the question whether other partnership transactions should be analyzed through the assets-over construct when the business of the partnership is continued.

A more specific application of the substance-over-form doctrine is formulated by the application of the step transaction doctrine. Under the step transaction doctrine, a series of formally separate steps may be recast as a single transaction given their integration and interdependence with one another.50 Thus, seemingly independent separate steps would be disregarded and viewed as one single step for purposes of determining the tax consequences of the transaction. Traditionally, the IRS and the courts have used three alternative tests to determine whether to invoke the step transaction doctrine: (1) the end result test; (2) the mutual interdependence test; and (3) the binding commitment test.51 The end result test focuses on the actual intent of the parties and inquires if separate steps were in fact part of a single transaction designed to reach the intended result.52 The mutual interdependence test asks if the legal relationships created by one step would be meaningless without the completion of the entire series of steps.53 Under this test, each step is examined to determine if it had independent economic significance or if its success depended upon the completion of all the steps.54 The binding commitment test looks to see if there was a binding commitment to undertake a series of steps, which may be stepped together.55

In the typical fact pattern involving a part-sale, part-contribution, the parties mutually agree and understand that the purpose of the rollover equity is to encourage the rollover sellers to remain engaged in the continuing business so that any accretion of value in the rollover equity is directly tied to the underlying business’s financial success. Thus, the bifurcation of consideration into a cash component and an equity component could be viewed as a single transaction in light of the parties’ mutual intent and documentation showing that intent. While most acquirers will provide some flexibility on the amount of rollover equity that is expected in the overall transaction, the general expectation (and requirement) is that a minimum amount of the purchase consideration will take the form of buyer equity. Although the contribution and sale of equity interests are viewed as separate steps, whether temporally or sequentially, the step transaction doctrine may recharacterize all the steps as integrated and mutually interdependent so that the resulting business enterprise in the new partnership form should be viewed as if the continuing partnership (and business) never terminated for federal income tax purposes. Likewise, a similar result would occur under the end result test and the binding commitment test. Taking this view, the partnership continuation (and merger) rules more accurately describe the true nature of the transaction.

While § 708(b) provides that a partnership will be considered terminated only if no part of any business of the partnership continues to be carried on by any of its partners, a question arises whether there is (or should be) a minimum threshold for “any” in determining whether a partnership has in fact continued. This issue becomes especially critical in a sale transaction with a rollover equity component whereby the rollover equity, generally reflected as a percentage of the PE buyer’s partnership (on a post-close, post-money basis), may vary significantly. As a general rule, the rollover interest ranges anywhere from 5 to 30% of the overall ownership interests in profits and losses of the PE buyer’s partnership. However, in some cases, the rollover interest may exceed the 50% threshold because of various tax and business considerations.56 In some situations, when the PE buyer’s partnership is old and cold57 in that it already has an operating platform with similar businesses and the rollover component is relatively small, sound minds would reason against continuation even though the “any” threshold under § 708 technically applies under the continuation rules. However, more guidance can be obtained from the application of the partnership merger rules in which the surviving partnership is generally determined under a mechanical test. Given many perplexing issues that arise in the case of the application of the ruling to a sale of a partnership with rollover equity as part of the purchase consideration, common sense may suggest that step transaction doctrine or general substance-over-form principles should prevail by recasting these transactions as partnership continuations subject to the application of merger rules under § 708.

Conclusion: Why It Matters

Even though it is common to assume that a PE buyer may not necessarily care about which approach is used because of the asset treatment and a step-up in basis of the assets upon acquisition by the PE buyer, the differences in the two approaches may have significant tax implications on the buyer. One of those issues is the sharing of the basis step-up between the buyer and the seller who becomes a member of the buyer’s partnership in accordance with the contribution in exchange for rollover equity. If the sale of the target is treated as a partnership termination under Revenue Ruling 99-6, the PE buyer will likely share the basis step-up with the seller. Under the ruling, the buyer’s partnership is treated as purchasing assets from the target. Upon the seller’s contribution to the buyer’s partnership, the seller, as a member of the new partnership, will be entitled to the benefits from depreciation deductions in accordance with its ownership interest and the terms of the buyer’s partnership agreement. The differences in the two approaches may affect the purchase price negotiations, the value of the rollover equity, and additional considerations for special allocations under the partnership rules.

Another significant consideration is the application of the anti-churning rules. Assuming that the anti-churning rules apply to the asset acquisition by the PE buyer, in the case of partnership termination, if the rollover component equals or exceeds a 20% threshold, the PE buyer will be subject to the anti-churning rules and will not be able to amortize any § 197 intangibles acquired from the target. On the other hand, if the sale of the target is treated as a partnership continuation subject to § 708 merger rules, the PE buyer can make an election under § 754 for its portion of the interests in the partnership in that the basis of the § 197 intangibles will be increased under § 743(b).58 Because the anti-churning rules are applied solely at the partner level, assuming the buyer and seller are not related, the goodwill of the continuing partnership should be amortizable under § 197(a) despite that the seller and the buyer’s partnership are related persons for this purpose.59 Thus, anti-churning considerations may require additional planning by both the seller and buyer.

While the differences in the two approaches (partnership termination versus partnership continuation) may be less material or critical than analogous issues in corporate transactions (for example, contributions under § 351, tax-free reorganizations, and so on), it is important to be aware of the differences and potential tax implications to sellers and buyers. The appendix provides a summary of the common issues and differences that may exist under each approach.

APPENDIX

Table 3. Comparison of Partnership Continuation/Merger (Section 708 and Treas. Reg. § 1.708-1(c)) and Partnership Termination (Section 708, Treas. Reg. § 1.708-1(b), and Rev. Rul. 99-6)

| Considerations | Partnership Continuation/Merger | Partnership Termination Rev. Rul. 99-6 |

| Employer identification number: Use of the same or a different EIN may affect contract arrangements and certifications, and have other business implications. | Use EIN of the continuing or resulting partnership (as determined under the § 708 merger rules). The terminating partnership may continue to use its historic EIN if the entity becomes a disregarded entity of the continuing partnership if the continuing partnership obtains its own separate EIN (CCA 201315026). | Use EIN of the acquiring entity. |

| Tax year | Tax year continues. | Tax year of the target terminates as of the closing date, and it will file a short tax year return. |

| Tax elections | Tax elections (for example, § 754 election, accounting methods, etc.) of the target will generally continue for the continuing or resulting partnership. | All elections of the target will terminate as of the closing date. |

| Basis in assets | For continuing partnerships and resulting partnerships, deemed purchased assets may be subject to a § 743(b) basis adjustment if a § 754 election is in place (by the terminating partnership). In a partnership merger, if no § 754 election is in place, the resulting partnership’s basis in the deemed distributed assets (in the assets-over form) will be determined under § 732 (carryover). Potential effects on post-merger basis in underlying assets. | N/A |

| Sharing in stepped-up basis of assets by buyer and seller | Basis increase is not shared in a continuation. For mergers that adopt the assets-over form, stepped-up basis is shared with rollover seller. | Basis increase is shared with seller. |

| Built-in gain recognition | Built-in gain rules will be governed by § 704(c) and depreciation methods chosen by the continuing partnership. | The members of the terminated partnership will be required to recognize built-in gain or built-in loss for the property under § 704(c)(1)(B) in the case of a contribution of built-in gain property within the prior seven years by the continuing partner or under § 737 in the case of the contribution of that property by the selling partner. Thus, recognition of built-in gain may be accelerated by termination. |

| Anti-churning: Depreciable and amortizable assets generally are not subject to the anti-churning rules. However, anti-churning rules may apply to assets that were not amortizable before the enactment of § 197 and that were acquired from a related person (as defined in § 267(b) and 707(b), except substituting 20% for “more than 50%”). | Anti-churning rules may not apply in the case of a purchase of partnership interest and § 754 election. | Acquisition of assets will likely be subject to anti-churning assuming rollover equity is equal to or exceeds 20%. |

| Holding period | The holding period in assets continues. | For the buyer’s portion of the purchased assets, the new holding period starts on the day of the acquisition. |

Related Topics

Notes

citation Duong and Lindsey, “Rollover Equity Conundrum in Transactions With Private Equity Funds,” 54 Colo.Law. 36 (May/June 2025), https://cl.cobar.org/features/rollover-equity-conundrum-in-transactions-with-private-equity-funds.

1. Rollover may also take the form of contributions in exchange for common stock in a corporation controlled by a buyer; however, the stringent control requirements of § 351 affect the use of corporations in most rollover transactions.

2. Before enactment of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), a partnership was considered terminated if either no part of the partnership’s activities continued to be carried on by any of its partners, or a sale of 50% or more of the total interest in the partnership’s capital and profits occurred within a 12-month period, also known as a technical termination. Under the TCJA, the technical termination rule was repealed for tax years after December 31, 2017.

3. See §§ 751(a), 1245.

4. The ruling is based on the holding of McCauslen v. Comm’r, 45 T.C. 588 (1966), and Rev. Rul. 67-65, 1967-1 C.B. 168, which held that in a two-person partnership, one partner’s acquisition of another partner’s interest is treated as acquisition of assets attributable to that interest, even though Treas. Reg. § 1.741-1(b) provides that the selling partner is treated as selling his partnership interest. See generally McMahon Jr., “Now You See It, Now You Don’t: The Comings and Goings of Disregarded Entities,” 65 Tax Law. 259, 259 (2012).

5. See § 197(f)(9)(A). See also more detailed discussion of anti-churning rules infra Conclusion: Why It Matters.

6. See generally Lutz and Mayo, “New York State Bar Association Tax Section Report on Revenue Ruling 99-6,” New York State Bar Association Report No. 1240, at 40–45 (June 13, 2011).

7. See Gall, “Nothing From Something: Partnership Continuations Under Section 708(a),” University of Chicago 2016 Federal Tax Conference (Nov. 12, 2016).

8. See Rev. Rul. 144, 1953-2 C.B. 212. See also id.

9. Treas. Reg. § 1.708-1(b)(1).

10. Id.

11. Id.

12. Id.

13. Sections 751 and 755 may recharacterize what otherwise would be capital gain from the sale of a partnership interest as ordinary income. This topic is beyond the scope of this discussion, but the selling partners should generally be aware of any gain recharacterization as a result of the “hot asset” rules.

14. Chester may have gain or loss as a result of the deemed distribution (e.g., distribution of cash exceeding basis). There may also be additional gain as a result of the operative rules of § 704(c), which will be discussed later.

15. Rev. Rul. 66-264.

16. See Laier, “Navigating Partnership Continuations,” The Tax Adviser (Apr. 1, 2023).

17. See §§ 741, 751, 755.

18. See Treas. Reg. § 1.708-1(b)(5).

19. See § 743(b).

20. See § 708(b)(2)(A).

21. See Treas. Reg. § 1.708-1(c)(5), ex. 1.

22. Another form may be known as interests-over. However, in the case of an interests-over transaction in which the partners of the merging partnership contribute their partnership interests to the surviving partnership, the merger will be treated as an assets-over transaction. See Treas. Reg. § 1.708-1(c)(5), ex. 4. See also Preamble, REG-11119-99, “Partnership Mergers and Divisions,” 65 F.R. 1572, 1573 (Jan. 11, 2000).

23. See Treas. Reg. § 1.708-1(c)(3).

24. See Treas. Reg. § 1.708-1(c)(3)(ii).

25. See Treas. Reg. § 1.708-1(c)(4). To apply this rule, the transaction documents need to specify that the resulting partnership is acquiring partnership interests from a particular partner of the terminating partnership. The selling partner must also consent to treat the transaction as a sale of that partner’s partnership interest.

26. The merger cash-out rule does not always produce favorable tax results for the parties involved. Consideration of whether the rule favorably applies should be evaluated before drafting any related provisions in a purchase or merger agreement.

27. This would likely be the case because Big Bend has an enterprise value that is five times greater than Alamo’s.

28. See Treas. Reg. § 1.708-1(c)(5), ex. 5.

29. If Alamo had a § 754 election in effect in the year of the merger, Big Bend would have had a § 743(b) adjustment for its share of the Alamo assets, and that adjustment is taken into account in determining Big Bend’s basis in the assets after Alamo liquidates under Treas. Reg. § 1.732-2(b). If Alamo does not have a § 754 election in effect in the year of the merger, Big Bend’s basis in the distributed assets would generally be determined under § 732(c). The underlying assets of Alamo will affect Big Bend’s post-merger basis in the underlying assets. For example, if Big Bend receives a share of ordinary assets, such as inventory with zero basis, the basis of the inventory would have been adjusted (to fair value) under § 743(b) but would not be increased under § 732(c).

30. See § 732(b). See also Treas. Reg. § 1.708-1(c)(5), ex. 5.

31. See Borden et al., “Avoiding Adverse Tax Consequences in Partnership and LLC Reorganizations,” American Bar Association Business Law Today (Dec. 31, 2013).

32. See § 704(c)(1)(B).

33. Situation 1 treats Alamo as distributing its assets to its partners and immediately liquidating. When the remaining one-third interest in the tangible property and building are distributed to Bailey and Chester, the rules under Treas. Reg. § 1.737-2(d)(1) treat the previously contributed property as coming out first so that any remaining pre-contribution gain is zero, so the mixing bowl rules under § 737 do not apply.

34. If Chester decided to sell a portion of his Alamo interest for cash, an interesting question arises about whether the transaction could still be characterized as a transaction governed by the ruling. The deemed contribution of property followed by a distribution of cash would likely be characterized as a disguised sale of partnership interests by Chester under § 707(a)(2)(B). There is debate on whether a transaction can be considered a disguised sale of partnership interests given the lack of regulations that implement the mechanics of the disguised sale. That discussion and the discussion of disguised sale of partnership interests is beyond the scope of this article.

35. See Borden, supra note 31.

36. See Treas. Reg. § 1.197-2(h)(12)(v).

37. See Treas. Reg. § 1.704-3(a)(8)(i).

38. See Treas. Reg. §§ 1.704-4(c)(4), 1.737-2(b)(1).

39. An alternative approach known as the pro rata approach would treat Chester as receiving an interest in Big Bend representing its pro rata share of all property transferred to Big Bend based on the fair market value. When compared with the tracing approach, Alamo’s distribution of the Big Bend interest in liquidation (via the assets-over merger) would cause Chester to recognize gain under the mixing bowl rules because his non-pro-rata share of § 704(c) property was distributed to the other partners.

40. See IRS, CCA 201315026. An old partnership merged into an existing disregarded entity held by a new partnership, while at the same time the partners contributed their interests in the old partnership in exchange for interests in the new partnership. When a partnership continues for federal income tax purposes (with a different legal entity name or jurisdiction), the new partnership does not need to obtain a new federal employer identification number. However, the facts of the advice imply that the new partnership had obtained a new federal EIN. The IRS concluded that the new partnership was considered a continuation of the old partnership even though the new partnership had a different federal EIN.

41. See Treas. Reg. § 1.704-1(b)(2). If the partnership experiences a down round during a revaluation event, the rules also require the partnership to “book down” the value of its assets, which will also have a direct effect on the capital accounts of the partners.

42. Huffman et al., Termination Upon Discontinuation of the Partnership Business (2024); Schliep, “IRS Aiming to Clear Up Partnership Terminations, Official Says,” Law360 (Oct. 26, 2022).

43. Jason Dexter, speaking on “Hot Topics in Partnership and Real Estate Taxation” panel, Federal Tax Institute (June 8, 2022).

44. The regulations (T.D. 8925) governing partnership mergers and divisions were finalized and published on Jan. 4, 2001, which is almost one year after Rev. Rul. 99-6 was published. Arguably, the provisions under § 708 and the guidance in the ruling are mutually exclusive so that the ruling should not apply if the facts of a transaction do not mirror those described in either situation 1 or situation 2.

45. See Gregory v. Helvering, 293 U.S. 465 (1935).

46. Frank Lyon Co. v. United States, 435 U.S. 561, 573 (1978). See also Comm’r v. Court Holding Co., 324 U.S. 331 (1945).

47. A detailed discussion of the substance-over-form doctrine is beyond the scope of this article.

48. See Field, “Fiction, Form, and Substance in Subchapter K: Taxing Partnership Mergers, Divisions, and Incorporations,” 44 San Diego L. Rev. 259 (2007).

49. See Preamble, REG-111119-99, supra note 22.

50. See IRS, ILM 200826004.

51. A detailed discussion of the step transaction doctrine is outside the scope of this article.

52. Penrod v. Comm’r, 88 T.C. 1415, 1429 (1987); King Enters. Inc. v. United States, 418 F.2d 511 (Ct.Cl. 1969).

53. Redding v. Comm’r, 630 F.2d 1169, 1177 (7th Cir. 1980), cert. denied, 450 U.S. 913 (1981).

54. Sec. Indus. Ins. Co. v. United States, 702 F.2d 1234 (5th Cir. 1983); McDonald’s Rests. of Ill. Inc. v. Comm’r, 688 F.2d 520 (7th Cir. 1982), rev’g 76 T.C. 972 (1981); Penrod, 88 T.C. 1415; Am. Bantam Car Co. v. Comm’r, 11 T.C. 397 (1948), aff’d per curiam, 177 F.2d 513 (3d Cir. 1949); Helvering v. Ala. Asphaltic Limestone Co., 41 B.T.A. 324 (1940), nonacq., 1940-1 C.B. 5, aff’d, 119 F.2d 819 (5th Cir. 1941), aff’d, 315 U.S. 179 (1942).

55. Comm’r v. Gordon, 391 U.S. 83 (1968).

56. In some cases, it may be beneficial to acquire less than 50% of the business because of various rules for benefits regarding affiliated companies; the buyer may want to leverage acquisitions by using the seller’s equity and keep the seller committed.

57. See Laier, supra note 16.

58. This assumes that the PE buyer platform is a newly formed vehicle and not a preexisting partnership. If the latter, the merger cash-out rule would apply for a buyer to benefit from a basis step-up for the assets that were acquired for cash.

59. Section 197(f)(9)(E); Treas. Reg. § 1.197-2(k), ex. 19. See also preamble to final regulations T.D. 8907, amending Treas. Reg. § 1.197-2(k) regarding basis adjustments.