Search and Seizure of Digital Evidence

March 2024

Download This Article (.pdf)

This article discusses warrants involving geofences and other electronic information.

The first time a geofence warrant came across my desk, I had almost no idea what I was looking at. My knowledge of such warrants was limited to the murder mystery podcasts I enjoy. Now I needed to determine whether to approve one—but first, I had to figure out what it was. As I read the affidavit, I looked for the elements of a typical search warrant: (1) an affidavit showing probable cause, (2) signed under oath or affirmation, (3) seeking to search a specific and particular person or thing. Yet, as I read the affidavit, I realized how little I knew about the techno-jurisprudential issues. That shouldn’t have surprised me—the few judges who have issued written orders on geofence warrants have lamented the dearth of precedent on the topic.

This article is intended as a brief guide for understanding search warrants related to electronic information, including geofence warrants. Since many of these areas of law are still developing, this article draws on sources nationwide but prioritizes the major Colorado cases. But before discussing warrants related to electronic information, it is necessary to understand the requirements of a traditional search warrant—that is, one not seeking electronic information.

Traditional Search Warrants

Law enforcement must typically obtain a search warrant to search a private area. Such a warrant overrides the general rule of the right to privacy that has been recognized as fundamental since before our nation’s founding. Indeed, the founders thought the right to privacy so vital that it was enshrined in the Bill of Rights:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches or seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the person or things to be seized.1

The Fourth Amendment’s privacy protection is a two-part provision addressing both the right and how it can be overridden. The second provision provides four requirements for a valid search warrant:

- probable cause,

- oath or affirmation,

- signed/approved by a neutral judge or magistrate, and

- specific and particular (a nexus is necessary).

This article focuses on a valid search warrant’s first and fourth elements.

Probable Cause

The first element for a valid warrant is probable cause. Much like negligence is judged by comparison with the ethereal reasonably prudent person in tort law, probable cause is based on an objective standard: Based on the totality of the circumstances, would a reasonable person believe there is a fair probability of finding contraband or evidence of a crime at the location sought to be searched?2 Based on this standard, one can see that probable cause has two subcomponents. First, probable cause requires that the items sought are seizable.3 Second, probable cause requires that the items will likely be found in the place to be searched. The standard is not mechanical and “does not lend itself to mathematical certainties and should not be laden with hypertechnical interpretations or rigid legal rules.”4

Because the standard for probable cause looks to the totality of the circumstances, the reviewing judicial officer does not have to make all inferences in favor of the person seeking the warrant. Instead, courts are required to consider facts that tend to undercut the likelihood of probable cause.5 For example, in People v. Smith, the Colorado Supreme Court held that a trooper who noticed a rental vehicle with out-of-state plates did not have probable cause to search an automobile for drugs because the K-9’s failure to alert to the car was stronger than the evidence suggesting drug activity.6 The mere possibility of an innocent explanation of a fact does not entirely necessarily negate the fact, but it affects the weight given to that fact when determining probable cause.7

Turning back to the first prong—probable cause requires the items sought (objects) to be seizable. An item is seizable under Colorado law when:

- it is stolen or embezzled;8

- it is designed or intended for use as a means of committing a criminal offense;9

- it is or has been used as a means of committing a criminal offense;10

- it is illegal to possess;11

- it is material evidence in a subsequent criminal prosecution in Colorado or another state;12

- its seizure is expressly required, authorized, or permitted by statute;13 or

- it is kept, stored, maintained, transported, sold, dispensed, or possessed in violation of a statute of this state, under circumstances involving a serious threat to public safety or order, or to public health.14

The object of the search may fall into multiple categories, but it is sufficient that it meets at least one category. This prong is rarely contested.

The second prong of probable cause requires a finding that evidence sought (the object) will likely be found because of the search. The analysis boils down to a simple question: Would a reasonable person believe this evidence will currently be found in this location based solely on common sense combined with what is written in the affidavit for the warrant? To make that determination, the court should consider, among other things, the source and age of the information, the strength of existing evidence, and whether the time and place specified in the warrant have a sufficient nexus to the evidence sought.

The rules of evidence do not apply in making this determination. Thus, a search warrant may be issued despite being based on hearsay if there is reason to credit that hearsay.15 It is also unnecessary that the information in the affidavit be based on the applicant’s personal knowledge. But there must be sufficient information to independently determine whether each person providing information for the affidavit had adequate knowledge to make the assertion and whether that person is credible.

As an example, take the statement in an affidavit that the officer “was told by an undisclosed informant that methamphetamine is being sold out of the house in question.” In that situation, the judge cannot know how the undisclosed informant knows this information or whether the informant is credible. The applicant can fix this issue by explaining how the source knew the information (e.g., “An undisclosed informant told me that methamphetamine is being sold out of the house in question. The informant has personally observed these sales over three weeks.”). Likewise, the applicant can fix a lack of credibility by adding information showing why this person is credible. There is no exclusive way to do so, but credibility is commonly built by stating the informant’s history of giving accurate information or by including information that corroborates the source. Thus, a much better statement would be:

An undisclosed informant told me that methamphetamine is being sold out of the house in question. The informant has personally observed these sales over a period of three weeks. Previously, this department relied on information from the same informant, and the information was accurate. Surveillance of the house also shows that the occupants are engaged in activities that are consistent with the informant’s information as to when they receive shipments of methamphetamine and when they sell it.

After considering the source of the information, one should consider the strength of the existing evidence. The applicant must include information that the judge may not otherwise know. The applicant should never assume that the facts speak for themselves. The applicant should draw the connections, even if the applicant knows that the judge reviewing this warrant is aware of specific facts. For example, the officer should not simply say that “there were small baggies found in the car.” Instead, the applicant should explain that “small baggies were found in the car. These baggies are routinely used to package methamphetamine for sale.” Those facts should be included in the affidavit in case the warrant is litigated or a different judge makes the probable cause finding.

Time should also be considered. In this context, time refers to whether the application is submitted sufficiently near enough to the information forming the basis of the affidavit to believe that the search would still find evidence. Whether evidence would have been found in a location a decade, a year, or possibly even a month ago is irrelevant. There is no bright-line test to tell if something is near enough in time to support probable cause. When determining whether too much time has passed to support the probable cause standard, one should consider what the applicant is searching for. If the items searched for are consumable or readily disposable, the time before the information is stale is far shorter than if the items searched for are more durable. For example, suppose the application is based on the mere possession of drugs from a sale on January 1. In that case, that information will probably be stale by February 1 since drugs are consumable and there is no specific reason to believe that the drugs would still be present an entire month later. On the other hand, if the applicant is looking for a firearm they believe was used in a murder, perhaps the time nexus would be sufficient even a year later because it is likely that the firearm still exists.

Next, the judge should consider the nexus between the object and the location. The application for a warrant must connect the information in the affidavit to the specific site to be searched. For example, imagine an application for a search warrant that seeks to search the hunting cabin of the suspect for narcotics. Yet all the evidence presented is limited to the suspect using narcotics at a nightclub. Since there is no reason to believe the evidence will be found at the cabin, the warrant should be denied. While obtaining a warrant for secondary locations is possible, there should generally be more information about why the applicant believes the object would have been transported to that location.

Specificity and Particularity

If the judicial officer finds probable cause to issue a search warrant, the fourth requirement, specificity and particularity, must then be met. In other words, the warrant issued must be specific and particular about what is being searched and what may be seized. Like the element of probable cause, there are two subcomponents to the requirement for specificity and particularity: the warrant must specify both the location (scope) and the object (what they are looking for) of the search. Both the location and object should flow from the probable cause analysis.

The location of the search. Warrants often list identifying features of the property they want to search, such as the street address, color of the home or car, vehicle identification number, license plate number, or owner.16 Regardless of the method used to identify the property, it is sufficient if an officer can determine the place intended with reasonable effort.17

The request should limit the scope of the search to the smallest area reasonably possible. Limiting the scope prevents a challenge to the warrant for being overly broad. Probable cause must be established for each place that is to be searched.18 In other words, just because law enforcement can show a connection to something the suspect owns does not mean they can search everything the suspect owns. For example, in People v. Eirish, a magistrate issued a search warrant for a premises that included a garage and a home. The warrant was challenged, and the Colorado Court of Appeals held that there was a basis “to conclude that probable cause existed for a valid search warrant with respect to the garage.”19 Yet the court held there was no probable cause for the home because the affidavit did “not allege any criminal activity in the home itself or by the residence of the home. In addition the affidavit fail[ed] to connect the broker to the residence beyond the officer’s observation of his entrance onto the property.”20

The object of the search. The object of the search must also be identified. Here, some historical context is helpful. The particularity requirement prevents the kind of general warrants (writs of assistance) the British government issued before the revolution.21 To protect from such broad intrusion, a warrant must “particularly describe the things to be seized [to make] general searches under them impossible and prevent[] the seizure of one thing under a warrant describing another. As to what is to be taken, nothing is left to the discretion of the officer executing the warrant.”22

Of course, knowing exactly what will be found is not always possible. Some courts have upheld warrants that authorized the search or seizure of classes of items when those items were tied to a specific crime.23 Yet the purpose of the particularity requirement is to assure “that the permitted invasion of a suspect’s privacy and property are no more than absolutely necessary.”24 So the warrant should clearly describe what objects are covered by the warrant and allow the officer to discern whether any objects are excluded from the warrant.

Searching Electronically Stored Information

While traditional warrants still constitute the bulk of requests, it is rare that a week goes by without seeing a request for a warrant to search a cell phone, Snapchat, Facebook, or some other source of electronic information. That, of course, is no surprise when one considers the pervasiveness of cell phones in our modern society. Yet a request to search cell phones and other electronics is distinct from a request to search a physical location because these items contain a vast amount of personal data. As noted by Judge Learned Hand nearly 100 years ago, “it is ‘a totally different thing to search a man’s pockets and use against him what they contain, from ransacking his house for everything which may incriminate him.’”25 Thus, it is important to consider the requirements for a search warrant in the specific context of electronically stored information.

Search Versus Seizure

As a preliminary matter, there is a difference between the seizure of a cell phone and the search of its contents. The leading case on this issue is Riley v. California.26 Before Riley, there was debate over whether the contents of a cell phone could be searched incident to arrest or under some other exception to the general rule that a warrant is needed to search. Riley answered that question: No. Yet officers can seize a phone and hold it until they can obtain a search warrant if they believe they have probable cause for a search.

However, the term “seizure” is ambiguous when dealing with electronic information. On the one hand, seizure could mean holding the cell phone until a warrant can be obtained. On the other hand, a seizure could mean copying the information without searching it. In the context of electronic information, it is best practice to take the minimum necessary steps to preserve the evidence. Given the proximity of the phone’s content, and the ability to preserve the evidence via less intrusive means, a court would likely view the copying of information as unreasonable until a warrant is issued.

Probable Cause for a Search

It is no secret that if someone committed a crime their cell phone may contain potentially incriminating information. The question, then, is how much of a nexus is required before being allowed to search a cell phone. For example, if a cell phone is found next to a bag of narcotics, is the physical connection constitutionally sufficient to search the cell phone? What about if there are enough drugs located with the cell phone to imply that the drugs were being held for distribution? What if there is also a ledger book showing drug transactions and listing phone numbers? There are numerous potential cell phone-related inquiries.

While the basic principles of probable cause apply in the context of electronically stored information, the applicant must often address and explain additional matters. It is necessary, logically, to first figure out what is being sought because the object of the search will affect the scope of the search. The probable cause related to the object for search warrants of electronics is much like the probable cause for tangible items. Even so, the probable cause associated with the scope of the search is different because of the nature of electronics.

First, like all warrants, the applicant should explain the source of the information. So, when law enforcement seeks to search an electronic device, they need to explain what precisely makes them believe there is seizable information on the device. There must be a connection between the crime and the use of the electronic device sought to be searched. That someone is suspected of a crime and has a cell phone is insufficient cause to search the phone.

Further, the mere fact that a cell phone was found on a suspect is unlikely to be sufficient to create a nexus between the alleged crime and the use of the phone. Yet the mere presence may be enough in some cases when cell phone use is tightly linked to the crime being investigated. But an explanation of why law enforcement believes the phone has information relevant to the investigation is necessary. The strength of that nexus will determine the scope of any permissible search. For example, an affidavit stating that a cell phone was found in a recovered stolen car driven by a suspect is likely insufficient to search the phone for messages and photographs. By contrast, if a cell phone is found with narcotics along with a book of phone numbers and drug deal transaction details, it is likely sufficient to search the phone’s call logs and text messages.

Another difference to think about when the object of the search is electronic information is the temporal aspect. Traditional warrants question whether the information will still be in a location. Electronic warrants also make that inquiry, but the applicant must offer a stronger limiting principle to satisfy the reasonableness requirement in the electronic context. For instance, imagine police are seeking messages related to a drug deal. In that context, there must be reason to believe that messages from that date would still be on the phone, but law enforcement also needs to limit the messages they review. They cannot search all the messages hoping to find any reference to the drug deal. While not possible in traditional warrants, the time period can be much more carefully constrained when searching electronic information. For instance, a search can be limited to messages from a specific day.

Finally, location considerations may have additional complications in the context of electronic information. Just as law enforcement could not search a cabin for drugs when the affidavit contains no connection to that location, law enforcement cannot search parts of the phone that are not supported by probable cause. For example, law enforcement may have probable cause to search a suspect’s cell phone for messages between two suspects during a set period, but that does not allow a search of photos held on that phone. With the rise of cloud computing, explaining the location of the evidence sought is becoming even more critical. Law enforcement may have a warrant to search a phone, but that warrant, unless specified, will not extend to the data held in the cloud simply because that data could be accessed by the phone user on the device. Thus, the warrant should specify whether it permits a search of any of the user’s data held in the cloud that can be accessed via the electronic device.

Specificity in Electronically Stored Data

Like the traditional search warrant, the particularity and specificity authorized in the warrant flow from the probable cause. Before establishing where the applicant wants to search, the issue of what the applicant can search for arises.

First, it is necessary to connect the object of the search with the probable cause. For instance, if the police set forth probable cause solely to search for and seize a rifle, the warrant cannot authorize the police to look for drugs. Likewise, setting forth probable cause to search text messages for drug distribution evidence does not mean that the police can also search the photos on the phone.

The more significant issue about the scope of the search is whether the scope of the object is sufficiently defined to allow law enforcement certainty as to what they can search for. But a search warrant is not defectively broad simply because it authorizes the search and seizure of many things.27 Thus, if a warrant authorizes the seizure of all child sexual abuse material, it is not overly broad simply because there are hundreds of photos found because of the search.

Since many investigators are not sure precisely what they will find, a helpful question to gut-check the scope of the warrant is: Could the applicant have made the warrant more specific without sacrificing the investigation’s integrity based on the information they currently know? If the answer is yes, there is a good chance the warrant is overbroad in scope.

For example, suppose that law enforcement wishes to search text messages between Suspect A and Suspect B related to a drug distribution they believe occurred on May 10. Law enforcement could request to search all messages between the two suspects. That request is likely overbroad. Instead, law enforcement could specify that they want to search for “text messages from May 3 until May 10 discussing setting up a meeting to purchase drugs, price of the drugs, or the quantity of drugs sought.” By being more specific, it is possible to mitigate the intrusiveness of the search.

Because of the sheer amount of information electronic devices can hold, the scope of the permitted search must be carefully limited. In People v. Thompson, the Colorado Supreme Court explained that “a warrant broadly authorizing police to search a cell phone for all texts, videos, pictures, contact lists, phone records, and any data showing ownership or possession” violated the particularity requirement of the Constitution.28 As a result, failure to sufficiently limit the scope of a warrant can quickly turn it into an impermissible general warrant.

The question becomes how particular the request must be to follow the particularity requirement. Since the ultimate touchstone for Fourth Amendment matters is reasonableness, the inquiry is whether the search was reasonably calculated to find evidence while being sufficiently curtailed to prevent “a general, exploratory rummaging in a person’s belongings.”29

To do so, the warrant must be constrained to a set period—especially when looking for one discrete piece of information. For example, in United States v. Bohannon, the court examined a search warrant that allowed law enforcement to review the contents of a suspect’s OneDrive account. The Bohannon court, in dicta, explained that “were law enforcement seeking only the child pornography image in the OneDrive account, the Court would . . . need to determine whether the warrant application’s failure to expressly state the date on which Microsoft identified the image is fatal to the magistrate’s probable cause finding.”30 Of course, because electronic information is usually seized as a whole but only searched in part, law enforcement can seek additional warrants if they find evidence to support an expanded search.

The exact period of a reasonable warrant is a fact-intensive question—but it will rarely exceed 30 days. If law enforcement knows the exact date that a crime is committed, the request should be limited to immediately before and after the crime. For example, if police are investigating a drug sale they believe took place on May 15, they can probably request text messages from May 14 through May 16. But without more, it would likely be overbroad to approve a search of all text messages from the entire month of May.

Other methods for limiting the generality of the search help protect a warrant from challenge. For example, if you are searching for text messages, it is good practice to specify who sent and received the messages, if known. Likewise, law enforcement should not ask for all photos, all text messages, or all contact lists. Seeing all used in an affidavit should be a red flag.

In short, while a traditional search warrant has affirmative search scope (you can search this place), a search warrant dealing with electronic information has a greater need to limit that scope to specific areas or dates within the more general scope.

Geofence Warrants

Another twist to the traditional search warrant is the geofence warrant. A geofence warrant reverses the process used in a typical search warrant. In the regular search warrant, law enforcement has a suspect. In a geofence warrant, law enforcement has a crime and some evidence of location but no suspect. Geofence warrant law is still developing, and leading cases have expressed concern “that current Fourth Amendment doctrine may be materially lagging behind technological innovations.”31

The Three-Step Geofence Process

Google, the recipient of most geofence warrants, uses a three-step process when responding to a geofence warrant. The distinction between the steps is critical as law enforcement usually has to return to the court for a follow-up warrant based on the information they receive from different steps.

Step 1. Law enforcement submits a warrant that requires Google to provide an anonymized list of all the Google users within a specific location (known as a geofence) during a given time. One issue that Google has identified is that “the sizes and timeframes of geofences ‘vary considerably from one request to another.’”32 While Google doesn’t have any set requirements for the size or time frame of the geofence, at least not publicly, it has begun getting more restrictive. Google will issue a letter to law enforcement that their warrant may be overbroad if the initial request seems to sweep in too many people. Assuming the warrant is up to Google’s standards,33 this information is turned over to law enforcement.

Step 2. After law enforcement reviews the data received from the first step, they can narrow down the list of devices of interest. Then, they can receive all the location information for the devices of interest rather than the mere knowledge that the device was in the original geofence area. Here, it is necessary to receive a second search warrant.

Step 3. Finally, at step 3, Google will provide account identifying information for those devices relevant to the investigation. Again, it is necessary to receive another warrant for this information.

General Constitutional Concerns With Geofence Warrants

Geofence warrants are incredibly powerful—and quite intrusive. One of the chief concerns about using these warrants is their tendency to sweep in users without probable cause to support a search. Yet a properly written application will significantly mitigate this concern.34

Imagine that a murder takes place at a hotel, and the murder weapon is found in a ditch a few miles away the next day. In step 1, law enforcement could ask Google to provide an anonymized list of users in each location. Let’s say that 10 phones are found in the geofence search for the hotel room on the day of the murder, and five phones are located near the location of the ditch where the murder weapon was discovered. Law enforcement should be able to cross-reference the devices and limit their request for more information to devices in both locations at the relevant times.

Yet the fact that law enforcement should narrow down the number of devices captured in step 1 does not relieve the judicial officer of their responsibility to ensure that the geofence warrant request is adequately limited in scope. The judicial officer is the last line of defense for the privacy interests of many uninvolved individuals. While a potential suspect may have a remedy in the exclusionary rule, “individuals other than criminal defendants caught within expansive geofences may have no functional way to assert their own privacy rights.”35 So it is up to the judicial officer to safeguard the sacred right to privacy. This can be done by requiring law enforcement to constrain the geofence size and time frame tightly.

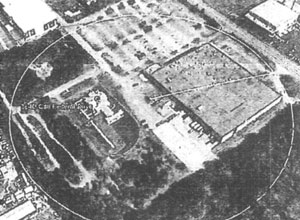

The precise contours of the geofence will depend on the facts presented. Even so, the best practice is to grant as small an area as possible. Geofence data can be rather detailed, so it is sometimes possible to constrain it to a specific location within a building (e.g., a hotel room within a larger hotel). The images below show examples of the geographic scope used in initial geofence warrants.

Image 1 shows the geofence that was ultimately held to lack particularized probable cause in United States v. Chatrie. There, law enforcement was looking for a suspect in a bank robbery. The suspect was seen in the wooded area near the bank, and law enforcement submitted the geofence warrant to figure out his identity. The warrant covers 17.5 urban acres, roughly the size of 18 football fields. Chatrie points out that judicial officers should be particularly critical of any request when the geofence zone includes areas where a person would have a heightened expectation of privacy. In addition, the Chatrie court was concerned that the geofence warrant “captured location data for a user who may not have been remotely close enough to the Bank to participate in or witness the robbery.”36 Ultimately, the Chatrie court found that the geofence warrant was overbroad.

Unlike Chatrie, the defendant in United States v. Rhine failed in his challenge to the government’s use of a geofence warrant. In that case, law enforcement used a geofence zone, shown in image 2, “slightly larger than but roughly tracing the contours of the [United States] Capitol building” to identify suspects related to the events of January 6, 2021.37

The government received the anonymized data from the original geofence zone, then narrowed that data down by excluding devices in the building before the breach of the Capitol. Because the building was closed to the public that day, law enforcement showed that the presence of a device that had not been present earlier but was present at the time of the breach suggested illegal activity. Also unlike in Chatrie, almost all the devices targeted for deanonymization in Rhine had a location within the Capitol building, and the margin of error fell entirely within the geofence zone.38 Because law enforcement did not have the discretion over which devices they deanonymized, used a much tighter geofence zone, and obtained follow-up warrants, the Rhine court held that the evidence was validly obtained. Both cases are instructive for Colorado criminal law practitioners.

Probable Cause and Particularity in Geofence Warrants

Like any other warrant, a geofence search must be based on probable cause. As discussed above, geofence warrants tend to be overbroad if not carefully constrained. The initial philosophical question that must be answered is whether step 1 in the geofence process constitutes a search.39 Several federal courts have held that step 1 is not a search—at least not one subject to objection.40 The third-party doctrine has significantly influenced these determinations. The third-party doctrine effectively exempts things shared with third parties from Fourth Amendment protection by holding that sharing that information (e.g., sharing location data with Google through an app) defeats any claim of a subjective reasonable expectation of privacy. However, Colorado has consistently rejected the third-party doctrine under its state constitution, diverging from the federal stance. While Colorado has not directly addressed whether step one of a geofence warrant constitutes a search, this article assumes that the answer is yes for state court purposes.41 Counsel must make their arguments under the proper constitution.

Since step 1 is likely a search under the Colorado Constitution, it is essential to address what constitutes probable cause for that step. The Colorado Supreme Court recently dealt with a reverse keyword search in People v. Seymour. While a reverse keyword search is not a geofence warrant, many of the concerns about probable cause are similar. In Seymour, the Court declined to determine “whether a search of [Google user search history] data requires probable cause individualized to a single Google account holder . . . .”42 This is similar to the question of whether step 1 of the geofence process requires probable cause. The Court invoked the good-faith exception to avoid the issue, leaving the matter to be resolved later. Yet multiple justices noted their concern about reverse searches and their tendency to act as a “digital dragnet.”43 Since at least three of the seven justices seem to believe that reverse search warrants may have trouble meeting the requirements of probable cause because they are based on nothing more than a hunch, this area is ripe for litigation. Previous cases addressing searches of large amounts of information have held that individualized probable cause is necessary for each intrusion of an individual’s constitutionally protected privacy interest, whether that interest lies in the individual’s person or records held by a third party.44

The Seymour Court implied that there is likely to be a strong focus on how the data search is conducted. The Court seems less concerned with a search conducted by a computer based on specific search parameters than a manual review by law enforcement. Therefore, counsel dealing with this issue in trial courts should work to develop the record around this issue. But if the Court ultimately agrees with Seymour’s three dissenting justices on probable cause, it will likely deal the death knell to geofence warrants as we know them.

No matter how probable cause is decided for step 1, steps 2 and 3 likely constitute a search and require probable cause. As with any probable cause determination, there must be a nexus between the information in the affidavit and the location to be searched. In the context of a geofence warrant, that nexus requires cell phone (or other electronic device) involvement. If there is no electronic device to send the information to Google, there is no reason to believe evidence would be found via a geofence search. Here, there is a bit of a split in opinion. On the one hand, there will likely be no direct evidence that a phone was present at the scene. On the other hand, since almost everyone always carries a phone, the reviewing judicial officer can assume that a phone was present in most cases. The latter is the prevailing view.45 Regardless, it is still best practice to include any known evidence that the suspect used a phone at these locations.

While it may be assumed that a suspect carried a phone, there must still be evidence that a crime took place and that evidence of that crime would be located in the geofenced area. Here, the four factors (source of information, strength of other information, time, and place) apply. The first two factors will be important for establishing that a crime occurred and that the area should be searched. The second two factors are used to select the geofence zone and time frame.

The judicial officer reviewing the request for a geofence warrant should carefully consider the proposed geofence size and time frame. The geofence should ideally include as small of an area as possible for as short of time as possible to avoid unwarranted intrusion on individuals who may have no involvement in the crime.

Conclusion

Even though technology has changed, the foundational principles of search warrants have stayed intact. Search warrants must still be particular and specific, and there must be probable cause to search each examined area. Whenever reviewing a search warrant, one should check that the request was narrowly tailored to avoid unreasonable intrusion into the suspect’s digital life. One way to do this is to look at the four factors addressed in this article: source of information, strength of information, time, and place. In addition, counsel dealing with suppression motions should develop the record of probable cause, or lack thereof, for the different steps of reverse search warrants. Whether such reverse warrants ultimately pass constitutional muster is yet to be seen. At least three current justices on the state supreme court are likely to find them unconstitutional. Counsel should carefully consider any evidence obtained with warrants for such data.

Related Topics

Notes

1. U.S. Const. amend. IV.

2. See, e.g., Mendez v. People, 986 P.2d 275, 280 (Colo. 1999).

3. Crim. P. 41.

4. People v. Bailey, 427 P.3d 821, 827 (Colo. 2018).

5. Those facts should also be included in the affidavit if known. While it is routine for affidavits to note that not all facts are included, law enforcement has a duty to present any facts that would substantially undercut their argument. See People v. Eirish, 165 P.3d 848 (Colo.App. 2007) (“The omission of material facts known to the affiant when executing the affidavit may cause statements within the affidavit to be so misleading that a finding of probable cause may be deemed erroneous. An omitted fact is material for purposes of vitiating an entire affidavit only when its omission rendered the affidavit substantially misleading to the magistrate who issued the warrant.”) (citing People v. Fortune, 930 P.2d 1341 (Colo. 1997)).

6. People v. Smith, 511 P.3d 647 (Colo. 2022).

7. People v. Zuniga, 372 P.3d 1052, 1059 (Colo. 2016).

8. Crim. P. 41(b)(1).

9. Crim. P. 41(b)(2).

10. Crim. P. 41(b)(3).

11. Crim. P. 41(b)(4).

12. Crim. P. 41(b)(5).

13. Crim. P. 41(b)(6).

14. Crim. P. 41(b)(7).

15. CRE 1101(d)(3); People v. Woods, 485 P.2d 491 (Colo. 1971). Indeed, search warrants are routinely issued based on information that the applicant has combined from several individuals (typically, but not exclusively, other officers).

16. Information about the owner may be useful to establish what is to be searched, but it is not a requirement. Eirish, 165 P.3d at 854 (“Indeed, there is no constitutional requirement that a search warrant name the person who owns or occupies the described premises.”).

17. Steele v. United States, 267 U.S. 498 (1925) (“It is enough if the description is such that the officer with a search warrant can, with reasonable effort ascertain and identify the place intended.”).

18. Eirish, 165 P.3d 848.

19. Id. at 854.

20. Id. at 855.

21. Maryland v. Garrison, 480 U.S. 79, 82 (1987) (“The manifest purpose of this particularity requirement was to prevent general searches.”).

22. Marron v. United States, 275 U.S. 192 (1927).

23. See, e.g., United States v. George, 975 F.2d 72, 76 (2d Cir. 1992) (“Although we have upheld warrants authorizing the seizure of ‘evidence,’ ‘instrumentalities’ or generic classes of items where a more precise description was not possible in the circumstances, the warrants in those cases identified a specific illegal activity to which the items related.”).

24. Id.

25. Riley v. California, 573 U.S. 373, 396 (2014) (citing United States v. Kirschenblatt, 16 F.2d 202, 203 (2d Cir. 1926)).

26. Riley, 573 U.S. 373.

27. People v. Tucci, 500 P.2d 815, 816 (Colo. 1972) (“the quantity of items listed in a search warrant or the quantity of items seized during the execution of a warrant does not necessarily have any bearing on the validity of the search itself”).

28. People v. Thompson, 500 P.3d 1075, 1079 (Colo. 2021) (emphasis added).

29. Coolidge v. New Hampshire, 403 U.S. 443 (1971).

30. United States v. Bohannon, 506 F.Supp. 3d 907, 917 (N.D.Cal. 2020). However, because law enforcement sought information to identify the owner of the account, the failure to limit the warrant to a specific date was not fatal.

31. United States v. Chatrie, 590 F.Supp. 3d 901, 915 (E.D.Va. 2022).

32. Id.

33. While Google’s refusal to comply with a geofence warrant has not been challenged in any Colorado court, perhaps Google would face show cause proceedings for failure to comply.

34. In People v. Seymour, 536 P.3d 1260 (Colo. 2023), the Colorado Supreme Court explained that filters and parameters in the warrant that reduce the scope of the search help to build a case that the search is reasonable.

35. Chatrie, 590 F.Supp. 3d at 926.

36. Id. at 930.

37. United States v. Rhine, 652 F.Supp.3d 38, 58 (D.C.Cir. 2023).

38. Id. at 58–59.

39. Id. at 91–92 (“In addition, it is far from clear that Defendant’s Fourth Amendment rights were implicated by the anonymized list provided at step one.”).

40. However, it remains to be seen whether Carpenter v. United States, 138 S.Ct. 2206 (2018), impacts the third-party doctrine when it comes to privacy in digital data. Carpenter held that the search incident to arrest exception did not apply to digital data held on a cell phone found upon a suspect’s arrest.

41. This assumption is based on Seymour, 536 P.3d 1260.

42. Id. at 1278 ¶ 60.

43. Id. at 1281 ¶ 81 (Marquez and Samour, JJ., dissenting).

44. Id. at 1277 ¶ 55.

45. See United States v. James, 3 F.4th 1102, 1105 (8th Cir. 2021) (“Even if nobody knew for sure whether the robber actually possessed a cell phone, the judges were not required to check their common sense at the door and ignore the fact that most people ‘compulsively carry cell phones with them all the time.’”) (quoting Carpenter, 138 S.Ct. at 2218).