The Benefits of Promoting Party Self-Determination in Mediation

October 2022

Download This Article (.pdf)

The rise of court-mandated mediation changes the perception of mediation as voluntary, which may influence the permanence of settlements reached in mediation. This article describes a study that investigated the causal role of party self-determination on settlement satisfaction by collecting data from litigators, mediators, and nonlegal professionals. It also explores ways to reduce post-mediation litigation by promoting party self-determination.

Post-mediation litigation is on the rise. Mandated court mediation is also on the rise. Professionals agree that parties must have self-determination regarding mediation outcomes.1 This article, and the research supporting it, explores the question: Is there a relationship between party self-determination during the mediation process and post-mediation litigation? Research for this article included a review and analysis of surveys completed by professionals participating in alternative dispute resolution processes, including judges, attorneys, and mediators. The findings suggest that participants with higher levels of self-determination in both the process and outcome of mediation are more satisfied with the mediation professionals involved in the process and the overall process itself. The results also suggest that higher satisfaction with the mediation process could result in a decrease in post-mediation disputes.

Self-Determination and Mediation

Self-determination is a fundamental tenet of mediation practice and is defined in Standard I of Model Standards of Conduct for Mediators:

Self-determination is the act of coming to a voluntary, uncoerced decision in which each party makes free and informed choices as to process and outcome. Parties may exercise self-determination at any stage of a mediation, including mediator selection, process design, participation in or withdrawal from the process, and outcomes.2

The purpose of the research conducted for this article was to determine whether litigation arising from mediation increases when participants exercise less self-determination during mediation (and vice versa).

Empirical Studies Illustrating the Benefits of Party Self-Determination

Empirical studies that observe the mediation process are rare, partly due to the confidentiality of the process. More studies on what happens during mediation are needed so that the legal field can better develop best practices based on observable, empirical data. The two studies discussed below provide a sample of what has been learned from direct observations of the mediation process. Together, the studies suggest that increasing party self-determination during mediation results in settlements that are more acceptable to the parties, and therefore, longer lasting.

The Maryland Study

A recent empirical study observing interactions between mediators and participants in child custody mediation supports our findings that increased perceived self-determination correlates with longer-lasting settlements. In 2018, Lorig Charkoudian, Jamie L. Walter, and Deborah Thompson Eisenber found that the amount of time spent in caucus was correlated with decreased long-term faith in parents’ ability to work together toward resolution of future custody disputes. This research study was conducted on 130 court-ordered child custody mediation cases involving 270 participants in Maryland (the Maryland Study). The researchers performed a follow-up survey approximately six months after each mediation session and found:

[T]he greater use of caucus was associated with an increase in participants’ sense of hopelessness about the situation from before to after the mediation and a decrease in their belief that they could work together with the other parent to resolve their conflict or that there was a range of options that could resolve their conflict.3

The Maryland Study found that caucus-style mediation decreased party interaction and diminished party perception of self-determination. In cases where the caucus was used more, parties were less likely to resolve custody disputes on their own six months after the mediation. Conversely, the Maryland Study found that a mediator’s use of joint brainstorming techniques increased parents’ belief that they could work together to resolve their conflicts with a range of options after the mediation. Brainstorming techniques included “asking participants what solutions they would suggest, summarizing those solutions, and asking participants how they think those ideas might work for them.”4

Although the Maryland Study did not include attorneys representing clients in mediation, it measured the effect of mediator evaluation, finding that mediator evaluation increased post-mediation litigation. When lawyers act as mediators, evaluation of the case becomes almost inevitable.5 Evaluative techniques, also known generally as “directive techniques,” include “explaining one party’s position to the other, and providing their own opinion and advocating for one participant or the other.”6 Mediator evaluation includes case analysis, assessment of strengths and weaknesses, predictions about likely court outcomes, and recommendations of specific settlement proposals.7 The Maryland Study found that when mediator evaluation is used, “the more likely the participants are to file an adversarial motion” after the mediation.8

The Maryland Study supports the concern that mediator evaluation lessens participants’ ability to exercise self-determination, resulting in perceptions of unfair mediation outcomes and increasing the likelihood of mediation litigation.9 Fairness of process and self-determination are interrelated. Individuals tend to perceive a process as fair when they participate in decision-making, are not coerced into making a decision, and have knowledge of the relevant information necessary to make a decision.10 Self-determination allows parties to problem-solve and resolve disputes on their own terms and based on their own values and interests. The joint session can be used to increase perceptions of fairness in the process, thus promoting longer-lasting settlements.

The New York Study

In the early 1990s, Dean G. Pruitt, Robert S. Peirce, Neil B. McGillicuddy, Gary L. Welton, and Lynn M. Castrianno gathered data through direct observation of 72 community mediations and found a direct correlation between party self-determination and long-term settlement satisfaction (the New York Study).11 The New York Study is another rare study where mediations were directly observed by the researchers, who also had mediation participants complete a follow-up survey. In this case, researchers contacted the disputants four to eight months after the mediation by telephone to discuss the status of the mediated agreements with each party separately. The researchers found that party participation in joint problem-solving behaviors and their perceptions of feeling heard directly impacted the long-term success of, and continued compliance with, mediated agreements.12 Interestingly, the New York Study found no relationship between short-term success and long-term success of mediated outcomes, noting that “long-term success is not a simple function of reaching an agreement or the quality of the agreement [in the short term].”13 Self-determination was a key distinguishing indicator of long-term compliance with mediated agreements. The researchers found that “joint problem solving contribute[d] to improved relations” between the disputants in the long term.14

Relevant Colorado Law

The Colorado Dispute Resolution Act15 authorizes courts to order mediation.16 Of Colorado’s 22 judicial districts, only three do not have a policy of issuing mediation orders.17 Seven judicial districts require parties to attend mediation.18 The remaining 12 judicial districts require mediation for certain cases (like eviction actions or small claims) or grant discretion to each judge to order mediation on a case-by-case basis. Most Colorado judicial districts use their right to order mediation, so many cases are subject to the mediation process. Therefore, there are substantial public policy reasons to ensure that parties are engaged in self-determination when mediating their disputes.

As courts order more cases to mediation, disputes arising from those mediations exemplify the importance of encouraging party self-determination in the mediation process. The Colorado Court of Appeals recently reaffirmed that mediation communications are confidential in Tuscany Custom Homes, LLC v. Westover.19 At issue in Tuscany was a decision by the trial court to declare a settlement was reached between three parties. The trial court relied on an unsigned, post-mediation writing as evidence of the existence and terms of an alleged oral agreement reached during mediation.

In Tuscany, the parties mediated their dispute and the mediation concluded without a signed document memorializing a settlement. Instead, the mediator sent an email listing the terms of settlement purportedly reached during the mediation and requested all counsel respond in agreement. Counsel for two of the three parties responded with their assent to the terms. One of those attorneys then drafted a settlement agreement based on the terms contained in the mediator’s email. The third party’s attorney responded that their client had no changes to the draft settlement agreement and indicated they would work with their client for a signature.

Two of the three parties signed the draft settlement agreement, but the third party refused because the agreement was missing a term material to the third party regarding a right to assert future claims. The two parties who signed the draft settlement agreement then moved the trial court to enforce its terms. The draft settlement agreement and the mediator’s email were offered as evidence that an enforceable contract between the parties existed. The Court of Appeals held that the mediator’s email and the draft settlement agreement were confidential mediation communications prohibited from being introduced as evidence of an enforceable settlement.

The Tuscany decision is important for two reasons. First, it upholds and expands the confidentiality of mediation communications under the Dispute Resolution Act as held in Yaekle v. Andrews.20 Second, it exemplifies how additional litigation may result when party self-determination is undermined during the mediation process.

This case presents a cautionary tale for attorneys who make representations about their client’s position without authorization. The third party’s attorney in Tuscany represented to the other two parties that the attorney’s client agreed with the terms of the draft settlement agreement when, in fact, the draft settlement agreement lacked a material term. The miscommunication between attorney and client resulted in an unsigned draft settlement agreement, additional litigation, a hearing and testimony in front of the trial court, an appeal, remand to the trial court, and further proceedings.

Tuscany exemplifies the importance and relevance of a client’s self-determination in settlement. Party self-determination as to the mediation process and outcome is undermined when an attorney speaks on behalf of a party without full authority. Post-mediation litigation follows, and settlement efforts are stymied. When clients are empowered to be part of the process and feel heard, settlement fortitude is more readily achieved.

The Colorado Survey

The authors developed a survey to isolate and study party self-determination in mediation. The following outlines the participants, procedure, results, and preliminary conclusions of the research.

Participants

Participants21 were recruited through various lawyer and mediator listservs and electronic communications. Most participants were attorneys (71.4%), and the rest were various other law professionals. About half of the participants (47.40%) reported having mediation training, though fewer (23.7%) reported practicing as mediators. On average, participants had 19.14 years of professional experience. Participants completed the survey online via Qualtrics.

Procedure

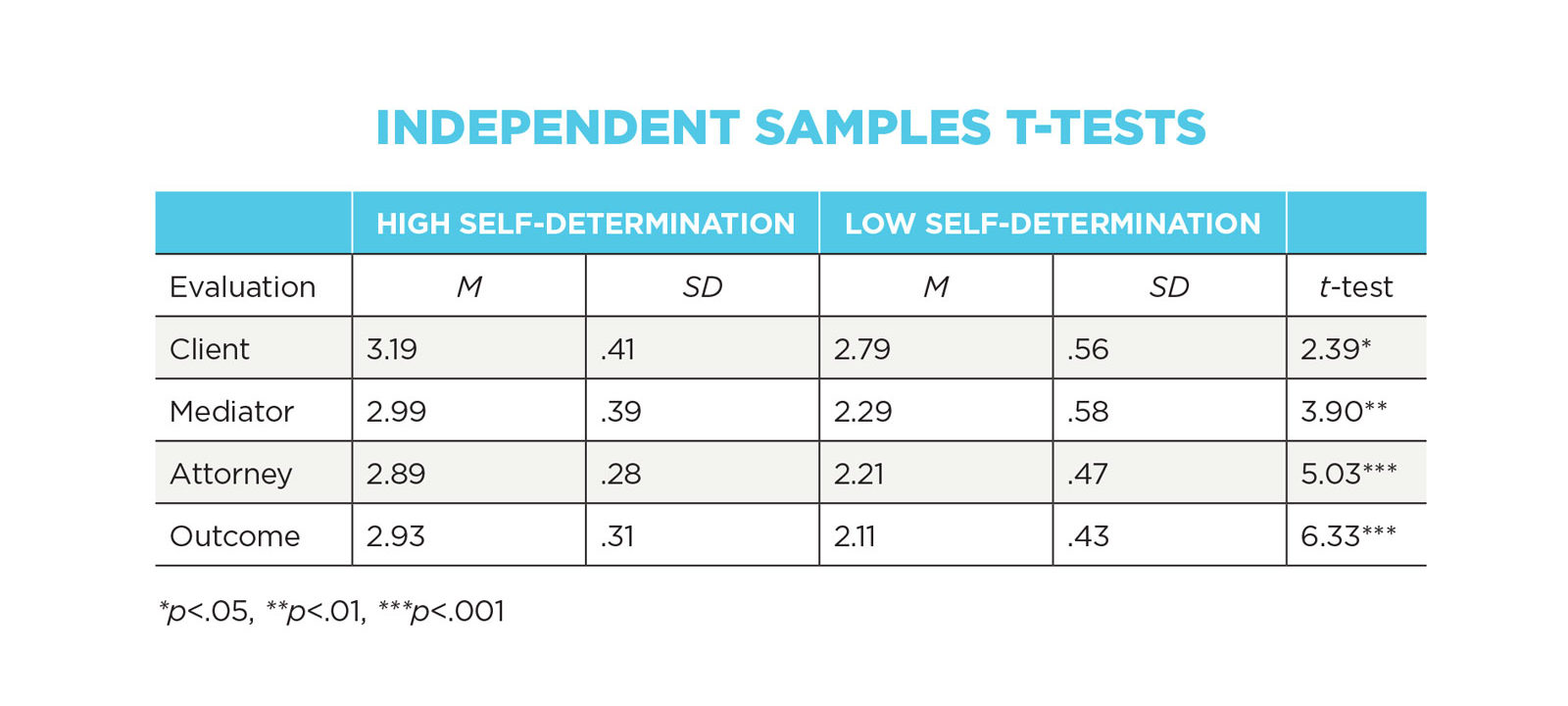

In this one-way experimental design,22 participants were each randomly assigned to a high or low self-determination group. Each group read a hypothetical scenario (involving a client named Saul, an attorney, and a mediator) describing a breach of contract complaint over a home remodeling job. The surveys were controlled to isolate and study the variable of party self-determination. The differences between the groups were examined using independent samples t-tests.

In both scenarios, the parties brought claims against each other, the subject client was represented by counsel who participated in the mediation, and the mediator used an evaluative mediation style. In both scenarios, the attorney advised the client that the case was not worth litigating. Although the client believed he was right, he agreed to pay a small sum to the opposing party in settlement. Both scenarios resulted in a signed settlement agreement.

In the high self-determination scenario, the parties voluntarily agreed to attend mediation and agreed on the mediator. The client met with his attorney to prepare for the mediation. The client heard the mediator evaluate both the strengths and weaknesses of his case and was encouraged by his attorney to share his story. The client felt heard and unpressured at mediation and had the choice to settle or not. The attorney and client reviewed the settlement agreement together before the client signed.

In the low self-determination scenario, the court ordered the parties to mediate and appointed the mediator. The client did not meet with his attorney to prepare for mediation, nor did he review the terms of the settlement agreement with his attorney before signing. The client heard the mediator only discuss the weaknesses of his case, and the attorney did all the talking at mediation. The client felt ignored during mediation and pressured to settle with little to no choice.

After reading the assigned scenario, each participant completed a survey consisting of four scales measuring their evaluation of the individuals featured in the scenario in addition to the probable outcome of the scenario. Each 4-point evaluation scale featured response options of Strongly Agree (scored as 4), Agree (scored as 3), Disagree (scored as 2), and Strongly Disagree (scored as 1). In each scale, higher scores indicated more positive evaluations. As a manipulation check, participants were also asked to assess the client’s exercise of self-determination on a scale of 1 (highest degree of self-determination) to 10 (lowest degree of self-determination).

- Evaluation of Client. Participants evaluated the client on the basis of how easy it might be to work with the client (e.g., “Saul [the client] is probably reasonable.”). Two items were reverse-scored.23 Cronbach’s alpha showed good scale reliability (.90).24

- Evaluation of Mediator. Participants assessed the mediator based on professional qualities (e.g., “The mediator is effective.”). One item was reverse-scored. Cronbach’s alpha showed good scale reliability (.90).

- Evaluation of Attorney. Participants assessed the attorney based on professional qualities (e.g., “Saul’s attorney appears trustworthy.”). Two items were reverse-scored. Cronbach’s alpha showed adequate scale reliability (.77).

- Evaluation of Probable Outcome. Participants assessed the probable outcome of the case by evaluating the client’s predicted response (e.g., “Saul [the client] will probably dispute the terms of settlement in the future.”). Three items on this scale were reverse-scored. Cronbach’s alpha showed good scale reliability (.83).

Results

Prior to hypothesis testing, we examined the degree to which participants in each self-determination group correctly perceived the client as having high or low self-determination. As expected, participants in the high self-determination group25 perceived the client as having significantly higher self-determination than those in the low self-determination group.26 This indicates that participants read the scenarios carefully enough to notice the intended experimental manipulation.27

Next, we examined whether self-determination affected participants’ evaluation of the individuals in the scenario and the probable outcome of the scenario. As hypothesized, the client, the mediator, and the attorney were rated more favorably by the high self-determination group than by the low self-determination group. Additionally, participants in the high self-determination group predicted a more favorable outcome of the case. The table summarizes the results.

Preliminary Research Conclusion

The survey results show that party self-determination is a causal factor in evaluating clients, mediators, and mediation outcomes. All variables in the test scenarios were nearly identical except for the party’s degree of self-determination—the surveys were designed to isolate and study that element. There is a statistically significant difference in the self-determination rates between the scenarios, suggesting that the scenarios accurately communicated the intended level of party self-determination. The results confirm that a party’s self-determination increases faith in the client, attorney, mediator, and mediation outcome. Therefore, promoting party self-determination yields positive reactions to the mediation participants and process.

The research supports the hypothesis that increasing self-determination in mediation will increase satisfaction with mediation outcomes and lead to less post-mediation litigation. The authors are conducting further research by studying post-mediation surveys of court-ordered participants to determine whether party self-determination correlates with attorney presence during mediation. This new study tests theories that court-mandated mediation without promotion of self-determination may increase the occurrence of post-mediation litigation. If this is true, does party self-determination in the process and outcome help reduce post-mediation disputes? Is the legal profession doing enough to educate legal professionals (attorneys, advocates, mediators, arbitrators, judges), clients, and members of the public about mediation so they may participate meaningfully in the process?

The answers to these questions may suggest that more should be done to educate legal professionals and members of the public about mediation. When courts require parties to attempt one form of alternative dispute resolution, success of the process depends on the parties’ satisfaction with the process. People engaged in dispute resolution processes who feel more in control of the process and outcome are more satisfied with the legal system and its participants. Such satisfaction may help parties resolve disputes early or possibly avoid the legal system altogether, which can reduce court docket size.

Conclusion

A growing body of research suggests that promoting party self-determination can strengthen settlements and reduce post-mediation litigation. If used properly, court-ordered mediation can support overarching policy goals of lessening the strain on the court system and encouraging parties to resolve their own disputes when possible. But how mediation best practices should be changed to encourage party self-determination is an open question. More research on the benefits of joint sessions as compared to shuttle mediation may provide opportunities to integrate self-determination into the mediation process and help parties avoid settlement remorse. The empirical research seems to support increased party involvement in decision-making if parties are to resolve (for the long-term), rather than merely settle (for the short-term), their disputes.

Related Topics

Notes

1. See e.g., Model Rule of Prof’l Conduct (MRPC) 1.2, cmt. 2 (Am. Bar Ass’n 1983) (decision to settle a civil matter must be made by client, not counsel); MRPC 1.0(e) (defining “informed consent”); MRPC 1.4 (lawyers have a duty to keep clients informed); Model Standards of Conduct for Mediators, Standard I. Self-Determination (Am. Bar Ass’n, Ass’n for Conflict Resol., and Am. Arb. Ass’n 2005).

2. Model Standards of Conduct for Mediators, Standard I. Self-Determination, supra note 1.

3. Charkoudian et al., “What Works in Custody Mediation Effectiveness of Various Mediator Behaviors,” 56 Fam. Ct. Rev. 544, 560 (2018). Maryland prohibits attorneys from attending child custody mediations in a representative capacity. Id. at 546. Studies have not addressed the effect of attorney presence in mediation.

4. Id. at 560.

5. Nolan-Haley, “Mediation: The New Arbitration,” 17 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 61, 84 (2012). (arguing mediator evaluation has become a substitute for arbitration).

6. Id. at 84. Mediators with subject matter expertise often employ evaluative techniques based on their individual experience and knowledge. Mediators who are also attorneys or retired judges, for instance, are often asked by parties to evaluate a case because of their expertise. Attorneys representing clients in mediation give legal advice to their clients involving the same or similar subject matter; however, mediators do not advise participants on how to proceed or what course of action to take. Mediator evaluation is not considered legal advice.

7. Id.

8. Id.

9. See Coben and Thompson, “Disputing Irony: A Systematic Look at Litigation about Mediation,” 11 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 43 (2006).

10. See Shapira, “A Critical Assessment of the Model Standards of Conduct for Mediators (2005): Call for Reform,” 100 Marquette L. Rev. 81 (2016).

11. Pruitt et al., “Long-Term Success in Mediation,” 17(3) L. and Hum. Behav. 313 (1993).

12. Id. at 328.

13. Id. at 325.

14. Id. at 327.

15. CRS §§ 13-22-301 to -313.

16. CRS § 13-22-311.

17. 2nd, 13th, and 14th.

18. 4th, 5th, 9th, 10th, 11th, 17th, and 18th.

19. Tuscany Custom Homes, LLC v. Westover, 490 P.3d 1039 (Colo.App. 2020).

20. Yaekle v. Andrews, 195 P.3d 1101 (Colo. 2008).

21. There were 38 participants—17 women and 18 men. The median age was 47.51.

22. Self-determination was the only factor being studied.

23. Reverse-scoring alternates the answer scale throughout a survey, which encourages participants to pay closer attention to questions.

24. Cronbach’s alpha measures the internal consistency reliability of a scale by comparing survey items to one another. The minimum acceptable alpha value is .70.

25. (M = 6.27, SD = 1.62).

26. (M = 2.94, SD = 2.22), t(32) = 4.78, p = .00.

27. External manipulation included reverse-scoring and other survey features intended to ensure survey participants would carefully read and understand the self-determination factors and questions.

Party self-determination as to the mediation process and outcome is undermined when an attorney speaks on behalf of a party without full authority.