Vader on Trial

Lessons on International Law From Everyone’s Favorite War Criminal

September 2023

Download This Article (.pdf)

This article introduces attorneys to the international law doctrines of the law of war, through a hypothetical war crimes trial of everyone’s favorite war criminal, Darth Vader.

With high-intensity armed conflicts going on in Ukraine and around the world, it’s only a matter of time before a prospective client strolls into your office, accused of some pretty serious war crimes.1 This article will help you hit the ground running on that case by introducing you to key concepts in the law of armed conflict (LOAC), through the hypothetical trial of the infamous war criminal Darth Vader. Even if you have no intention of taking such cases, having a basic understanding of LOAC can help you better understand important current events as they unfold, and better understand their international law implications.

Forum

Somehow, we’ve managed to capture Mr. Vader. Before we can charge him with any war crimes, we would need to decide the issue of forum. Where can we prosecute such a unique defendant? Civilian courts, military courts, and international tribunals can all have jurisdiction to try alleged war criminals in certain circumstances.2 Each type of court3 has done just that in the past, with varying levels of success.4 But only so much justice can be served by any one state’s civilian or military courts for a defendant who, like Vader, has (allegedly) committed a staggering number of atrocities against a number of people. Our international war crimes court, the International Criminal Court (ICC), is not an option in this case, as no one had the foresight to extend its jurisdiction over extraterrestrial defendants.

Since Vader’s offenses affect so many members of the international community, while still escaping the ICC’s jurisdiction, the venue would most likely be an ad hoc international tribunal. Like the tribunals that convened in Nuremberg to try Nazi war crimes, in Manila to try Imperial Japanese war crimes, and in The Hague to try former Yugoslavian war crimes, this tribunal would likely have a panel of judges made up of leading international law scholars and jurists, as well as a team of defense attorneys and prosecutors drawn from the various victim states.

Extraterritorial Jurisdiction

Once our tribunal convenes, the defense will undoubtedly move to dismiss all charges for lack of jurisdiction. As international law scholar Richard Baxter once put it, “The first line of defence against international humanitarian law is to deny that it applies at all.”5 But Vader would have a point: How does any court on Earth have jurisdiction over crimes allegedly committed “a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away”? Adolph Eichmann raised the same question at his trial. As an SS commander, he oversaw the execution of Hitler’s “Final Solution,” systematically murdering about 6 million Jewish people and millions of others.6 After the war, he fled to Argentina and kept a low profile—at least until 1960, when a team of Israeli commandos stopped by and offered him a free trip to Jerusalem.7 There, Israel’s attorney general arraigned him in the city’s district court on charges of “crimes against the Jewish people, crimes against humanity, and war crimes.”8

For most of his trial, Eichmann famously leaned on the so-called Nuremberg defense to argue that he was merely following orders.9 He stuck to this defense even with his last words: “I had to obey the rules of war and my flag.”10 But first, he argued that Israel could have no jurisdiction over alleged offenses that took place a long time ago (before the state’s very existence), in a land that was far, far away.11 The prosecution disagreed, arguing that his atrocities were so universal in character that they were not only offenses against specific peoples or states, but also offenses against the international order itself. As such, any state—even new ones—should have jurisdiction to prosecute a defendant like Eichmann.

The court found that it had extraterritorial jurisdiction over Eichmann and his offenses.12 It reasoned that his offenses did not take place a long time ago or in a land far, far away because Israel inherited the sovereign status of the British Mandate, the Jewish population of Palestine actively participated in the Allied struggle against Nazism, and Eichmann himself visited Palestine in 1937 to coordinate with its virulently anti-Semitic leadership.13 In addition, his offenses harmed the State of Israel by depriving it of millions of citizens, and about half of all Israelis were either Holocaust survivors or relatives of Holocaust victims.14 The court also found that Eichmann’s actions were “grave offenses against the law of nations itself” and therefore afforded jurisdiction to any member of the international community.15

That concept has since developed into the modern-day doctrine of universal jurisdiction.16 Under this doctrine, war criminals can be prosecuted wherever they are found because their crimes are crimes of international concern.17 The issue of retroactively applying law would also not apply here, because however long ago the events of Star Wars took place, clearly they weren’t that long ago if we somehow managed to capture Vader alive. With the preliminary issues of venue and jurisdiction out of the way, let’s consider what offenses Vader allegedly committed.

Episode I: The Phantom Menace

Vader is a 9-year-old in The Phantom Menace, born as Anakin Skywalker. He is a slave, but he quickly earns his freedom in a dangerous race, and then joins a pair of Jedi space wizards on a diplomatic mission.18 Being very responsible adults, they immediately bring him into a war zone and let him join the fight as a child soldier.

Fighting as a child soldier—would this be Vader’s first offense against the law of armed conflict?19 In most areas of criminal law, our answer lies in a statute that defines all of the offenses, their elements, and key terms. To keep things interesting, the rules governing lawful wartime conduct are spread across dozens of treaties. Each of these treaties has its own unique array of signatories, and its own unique way of defining hardly any key terms. The laws of armed conflict also derive from the norms of states engaged in war (“customary international law”), like a common law of war.20

Is there any treaty or norm addressing child soldiery? In fact, there is. The Hague Convention of 1907 and Geneva Conventions serve as the foundational texts of the law of armed conflict, and they receive occasional updates from treatises known as the Additional Protocols.21 In Article 4(3), the Additional Protocol of 1979 establishes an age limit to soldiery: people under age 15 “shall neither be recruited in the armed forces or groups nor allowed to take part in hostilities.”22

Given this language, Anakin’s Jedi friends might want to lay low for some time, having let an underage child take part in hostilities. But Anakin himself commits no offense by fighting as a 9-year-old. To the contrary, child soldiers who are captured are typically treated as victims, not offenders. Like any other combatant, though, l’enfant Vader is lawfully targetable by hostile forces for as long as he fights, and he can still commit a war crime while fighting.23 As repulsive as it may be to target child soldiers, combatants and noncombatants alike have a right to self-defense, and letting children fight in safety would only encourage bad actors to arm even more children. Episode I does not depict him committing a war crime, leaving his prosecutors with nothing to charge him for—so far.24

Episode II: Attack of the Clones

In Attack of the Clones, Anakin is a 19-year-old serving as a bodyguard for Senator Padme Amidala. He has a mixed record as a guardian, considering that he goes beyond the call of duty to save her life several times and even chases down a would-be assassin, but he also spends the entirety of the film sexually harassing her.25 That peacetime misconduct is neither here nor there, though. The LOAC analysis picks up toward the middle of the film, when Anakin starts having nightmares about his mother.

Concerned, Anakin abandons his post to visit her on the desert planet of Tatooine. There, he learns that a nomadic group, the Tusken Raiders, has abducted her. He tracks down a Raider campsite and finds her there, gravely injured. She dies in his arms. In a fit of rage, he unsheathes his lightsaber and starts striking down every Raider in sight, just as the camera cuts away. If there is any uncertainty about what happened, he later admits to Amidala that he killed everyone in the camp, including women and children. (She marries him anyway just a few scenes later.)

The massacre of the Raiders certainly sounds like a war crime, but is it? There is no shortage of international treaties that prohibit the intentional targeting of noncombatants during an armed conflict, but is there an armed conflict in this scene? Anakin’s attack can only be a war crime if there is a war going on.26 If the massacre is unrelated to any armed conflict, it is certainly still tragic and worth prosecution, but the governing law would be Tatooine’s criminal code, or perhaps the code of Jedi ethics, but not international law.

The main armed conflict in Episode II pits the Galactic Republic against a separatist movement of breakaway planets. Assuming that planets are the equivalent of states, Episode II’s armed conflict involves violence between two or more states, and therefore falls into the category of armed conflict known as international armed conflict (IAC).27 An IAC is what we would colloquially refer to as “war.” The Raiders belong to neither side in that IAC. Their raid, and Anakin’s counterraid, serve neither side in that IAC. Instead, the Raiders raided Anakin’s family because Raiders raid; it’s just what they do. Like the pirates operating off the coast of Somalia, the Raiders might have no idea that there is even a Star War going on around them.

But because these Raiders have such a passion for raiding, they may have started another kind of armed conflict: non-international armed conflict (NIAC). A NIAC is what we would colloquially refer to as a civil war, civil unrest, an insurgency, a guerilla war, a rebellion, or any number of similar terms, depending on the context. Definitions for NIAC vary, but for the sake of simplicity we can defer to the definition adopted by the Yugoslavian war crimes tribunal, which found that a NIAC involves prolonged violence between organized armed groups (OAGs).28 Generally, two elements must occur for a NIAC to exist: (1) the hostilities have reached a level of intensity that exceeds criminal conduct (e.g., the hostilities are of a “collective character”); and (2) the government has found it necessary to use the military rather than mere police forces to manage the situation. The Raiders are an OAG, as opposed to being simply individuals who each raid on their own, and their violent raids have been going on for so many generations that raiding is right there in their group name. That may be enough for the tribunal to conclude that Anakin’s attack took place during an ongoing NIAC between the Raiders and, well, everyone else on Tatooine.

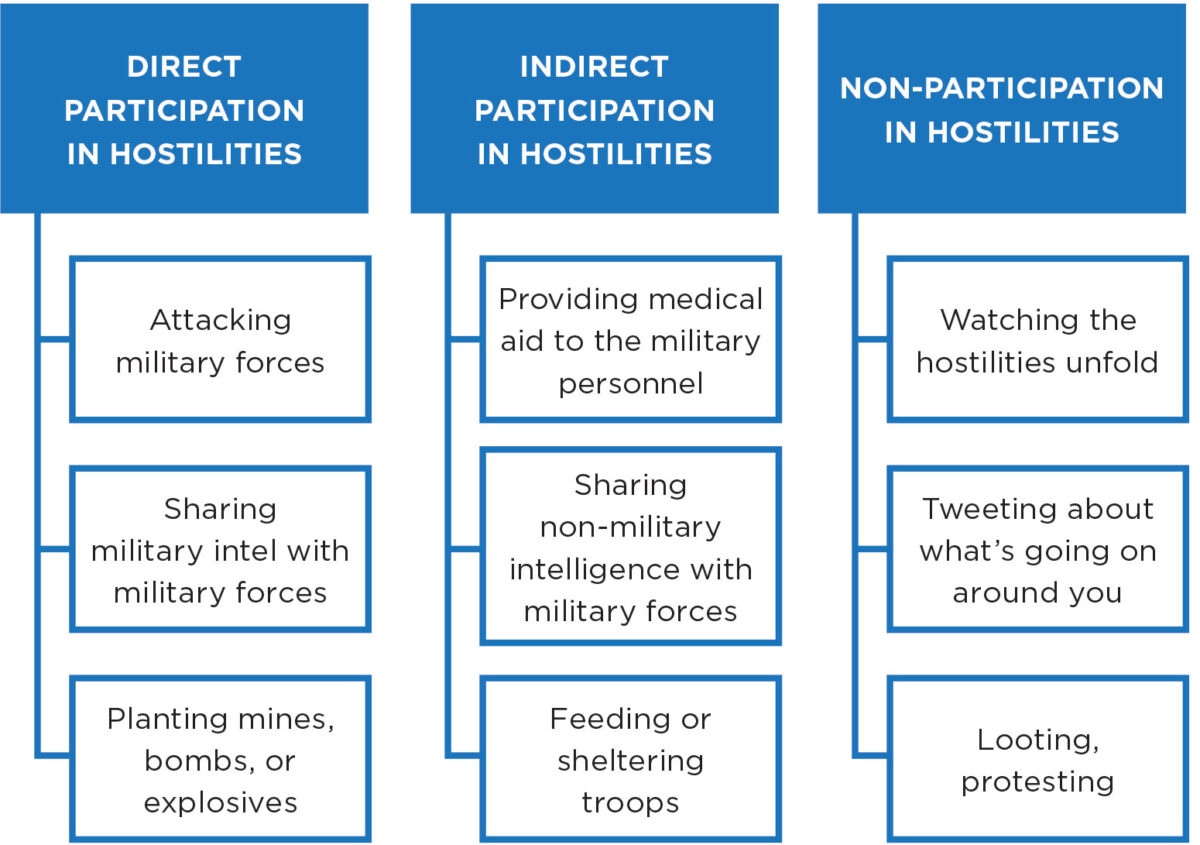

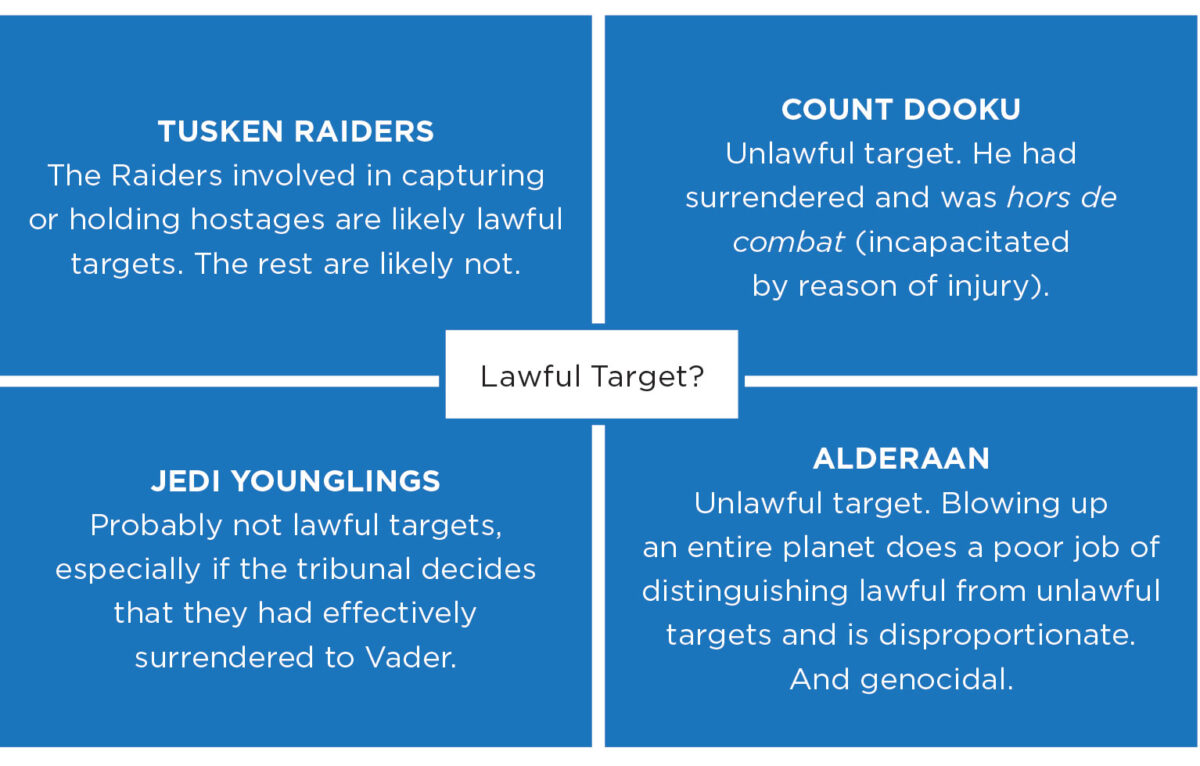

By that logic, the law of war does apply, and it requires belligerents to distinguish between lawful targets and unlawful targets.29 Intentionally targeting an unlawful target would be a serious war crime. Combatants are lawful targets, but there is no universally agreed-upon definition for who is a combatant. To keep it simple, let’s defer to the Bush Administration’s definition of “combatant” as “someone who is combating.”30 Were all the Raiders in this camp “combating”? Even if some of them are civilians instead, not all civilians are unlawful targets. They are lawfully targetable if they are directly participating in hostilities (DPH), and raiding is about as hostile as it gets.31 Their latest raid was ongoing when Anakin attacked, seeing as his mother and others were still being held hostage in the camp when he showed up.

But Anakin made it clear that he didn’t attack only the hostage-takers; he struck down everyone. Was everyone in the camp DPH, simply because there were hostages in the area? The films tell us little about Raider culture. Perhaps they believe families that raid together, stay together. Perhaps all Raiders are actively involved in guarding and/or torturing hostages? Civilians are only lawfully targetable while directly participating in hostilities, so it would be hard for this defense team to explain why Anakin’s targets were all lawfully targetable.

But it is the prosecutor’s burden to demonstrate that someone in this camp was an unlawful target. While common sense strongly suggests that surely not everyone was DPH in that moment, one wonders how the prosecutors would prove it. Anakin’s attack took place many movies ago, Anakin himself was the only survivor, and the desperate scavengers of Tatooine would have taken apart the campsite and all its physical evidence soon after the attack. So, as unlawful as this attack seems, Episode II does not offer enough evidence to convict Anakin beyond a reasonable doubt. This illustrates why it is so imperative to preserve evidence and testimony, before witnesses disappear or die and evidence gets washed away by the inherently hectic environment of a battlefield.32

Episode III: Revenge of the Sith

Episode III opens with 22-year-old Skywalker and his Jedi mentor, Obi-Wan Kenobi, leading a rescue mission. They shoot their way into a spaceship and manage not to commit any war crimes in the process—a remarkable feat for a pair of Jedi. Once aboard, they find the captive chancellor of the Republic and seize his captor.

The chancellor urges Anakin to kill his detainee, Count Dooku. Anakin refuses, offering a rare example of someone in Star Wars actually complying with the law of war.33 Clearly, even in the Star Wars universe, there is something unlawful or at least dishonorable about killing detainees. But the chancellor insists (“Do it”), and at that point Anakin obeys. In so doing, he commits a grave breach of the law of armed conflict—a serious violation defined by Article 50 of the First Geneva Convention:

Grave breaches . . . shall be those involving any of the following acts, if committed against persons or property protected by the Convention: wilful killing, torture or inhuman treatment, including biological experiments, wilfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health, and extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly.34

Combatants must adequately shelter and feed detainees, and they must treat detainees humanely—for example, by not murdering them.35 Yes, Dooku is himself a prolific violator of the law of war, but only a tribunal can punish him for these offenses, and only after a fair trial.36 While the legal analysis of “no extrajudicial executions” is straightforward, proving the offense would be more difficult. Only Anakin and the chancellor witnessed this extrajudicial execution, and the chancellor (*spoiler alert*) dies two episodes later, without having testified in a tribunal or having been deposed. He even manages to die once again in the sequel trilogy, so he’s definitely dead now. Given that, one wonders how the prosecution team would ever learn of this offense, let alone prove it.

Helpfully for the prosecution team, Anakin’s atrocities have only just begun. A few scenes later, he decides to help the chancellor engage in some light treason. For that, the chancellor (Emperor Palpatine) knights him as Darth Vader and orders him to execute Order 66. This order labels all Jedi as traitors, lawfully subject to summary execution under Imperial law (but still a LOAC violation). Anakin heads to the Jedi Temple, where he fights with various Jedi off-screen before turning his lightsaber on a room full of younglings. These are children, training to become Jedi.

Now, Vader’s defense team has the unenviable task of explaining why each of these children was lawfully targetable.37 In turn, we need to determine their status. Are they civilians, and therefore only lawfully targetable while directly participating in hostilities? Or are they combatants, and therefore lawfully targetable at all times? They were certainly civilians before they started their paramilitary Jedi training, but at what point in their training do they achieve combatant status? Are they like the cadets at the US military academies, who would be considered combatants by their own armed forces from the day they show up to school?

The movie offers no details on the nature of this training, or how far into it they had advanced. As such, there is not enough information to know whether this training is enough to turn them into combatants, or, if they are still civilians, if this training is enough to constitute DPH. The tribunal could moot all of this status-based inquiry anyway, by determining that, whatever their status might have been, they must have surrendered to Vader. In this scene, they were unarmed, not resisting, and in hiding when Vader found them. Surrendered persons, even combatants, are not lawful targets and are at least entitled to humane treatment.38 Depending on their status, they may be entitled to formal prisoner-of-war protections, but the baseline for humane treatment is Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions.39 The Obi-Wan Kenobi TV show indicates that some younglings even survived this attack, so the prosecution team may finally be able to find evidence of the incident and charge Vader for it.

Rogue One and the Original Trilogy

The role that Vader plays in the plot of Rogue One is as factually minor as it is legally significant. The plot in this film, like the plot in most Star Wars films, involves a group of rebels trying to destroy the Death Star, which is a giant, planet-destroying laser. About halfway through the film, Vader meets with the Death Star’s commander and scolds him for using it to blow up a city full of people. In this scene, his status has shifted dramatically from the prequel trilogy. As a combatant, he had personal liability over his actions. Now, as a commander, he has personal responsibility over his actions and the orders he issues, as well as command responsibility over the acts of his subordinates. Under the concept of command responsibility, often referred to as the “Yamashita Rule,” commanders owe a duty to ensure that their troops comply with LOAC.40 They breach that duty by failing to take reasonable precautions to discourage troops from violating LOAC.41 For Vader and modern military commanders, the command responsibility rule is a powerful incentive to maintain control over the potentially unlawful acts of their subordinates, on pain of prosecution.

Has Vader failed to take reasonable precautions here? He verbally reprimands this Death Star officer, so he’s doing more than nothing. But that seems like quite the slap on the wrist, when the misconduct involves blowing up an entire city. Then again, even just a reprimand might be serious enough when it’s coming from a space wizard who can choke people just by pointing at them. Whatever the tribunal decides about the sufficiency of that reprimand, it will have an easier time holding Vader responsible for the Death Star’s later attack on the planet Alderaan, in Episode IV—an attack that callously disregarded the law of armed conflicts of proportionality and distinction by killing everyone on the planet—rebels, civilians DPH, civilian noncombatants, children, the elderly, and every man, woman, child, and animal on the planet. Vader may not have ordered the attack or even participated in it, but he did nothing to stop it. As someone serving in a leadership role on the Death Star, he would bear command responsibility for the Death Star’s war crimes.42

Is there any room to argue that Alderaan was lawfully targetable? Episode IV establishes that this is a pacifistic planet with no army, so there seem to be no lawful targets on this planet to put in this weapon’s crosshairs, or if there were rebels on the planet, destroying the entire planet was clearly disproportionate. On top of that, what lawful target would be so important as to justify killing millions of noncombatants?43 Proportionality is a key factor in the legal analysis of military operations, and it balances the anticipated advantage of an attack with the anticipated harm to noncombatants and their property (“collateral damage”).44 While there is no specific or strict X/Y axis linear guide for judging proportionality, blowing up a planet full of noncombatants, even if a few rebels were, in fact, interspersed, is about as disproportionate as it gets.

In addition, blowing up a planet could qualify as genocide, which is a fairly serious war crime. This attack could constitute not just one act of genocide, but hundreds—one for each of the planet’s races, nations, and cultures, if the purpose of the attack was to destroy these peoples. And unlike most of Vader’s offenses, there is ample evidence of this one—the debris of blown-up planets is hard to miss. His attack on the younglings, and anything else he has done in furtherance of Order 66, is likely an act of genocide as well. After all, not anyone can become a Jedi. They are not merely a paramilitary group. Instead, only certain people who are born with Force abilities can become Jedi. Order 66 likely perpetrates a genocide by intending to bring about their extermination.

Conclusion

Vader commits plenty of other war crimes, but nothing tops genocide. Genocide is a grave violation of the law of war, and the evidence for Vader’s acts of genocide, against the Jedi people and the peoples of Alderaan, is more readily recoverable than his other offenses. As such, his prosecution would likely focus on his role in executing Order 66 and his command responsibility over the Death Star, and the graveyard of moons and planets that it left in its wake.

Of course, none of this ever happened, and Vader is only everyone’s favorite fictional war criminal. But drawing on these fictional events and their real-world analogs can help more vividly illustrate the rules and norms of war. And in today’s society, where hardly a week goes by without headlines involving war crimes accusations, you need to understand these rules and norms if you want to understand the world.

Related Topics

Notes

1. As unlikely as it might be that you would ever have a prospective client accused of war crimes, it’s not unheard of for ordinary Americans, far away from any battlefield, to be charged with and even convicted of serious war crimes. In United States v. Bond, a woman discovered her husband’s infidelity and retaliated by spraying his girlfriend’s doorknob with a chemical. 681 F.3d 149, 150 (3d Cir. 2012). After reviewing the case, the local prosecutor decided that this was more than criminal battery; it was a violation of the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention, 32 I.L.M. 800 (1993), as implemented in the United States by the Chemical Weapons Convention Implementation Act of 1998, 18 USC § 229. Id. The jury agreed, and the Third Circuit affirmed that conviction. Id. Ultimately, the US Supreme Court ruled that the Act was inapplicable to this case, because the “chemicals in this case are not of the sort that an ordinary person would associate with instruments of chemical warfare.” Bond v. United States, 572 U.S. 844, 861 (2014). After all, this chemical attack did nothing more than “cause discomfort, that produced nothing more than a minor thumb burn,” compared to, say, a chemical attack that could “poison a city’s water supply.” Id.

2. Vagts and Meron, “So-Called ‘Unprivileged Belligerency’: Spies, Guerrillas, and Saboteurs,” ch. 2 in Baxter, Humanizing the Laws of War: Selected Writings of Richard Baxter 37, 41–42 (Oxford Univ. Press 2013) (noting that under international law, suspected offenders against the law of war may be tried in civil or military tribunals).

3. Civil liability for wrongful international acts (including terrorism and tortious “war crimes”) is possible, as well. In US law, the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, 28 USC §§ 1330 et seq., permits foreign sovereigns to be made subject to the jurisdiction of US courts in certain limited circumstances and could be the subject of an entire separate essay.

4. Attorney General of Israel v. Eichmann, 36 Int’l L. Rep. 277 (Sup.Ct.Isr. 1962) (charging Adolf Eichmann with war crimes in Jerusalem’s civilian district court); Al Bahlul v. United States (Al Bahlul IV), 967 F.3d 858, 863, 877 (D.C.Cir. 2020), cert. denied, 142 S.Ct. 621 (2021) (reviewing the conviction of an Al Qaeda terrorist in a US military commission); Prosecutor v. Šainović, No. IT-05-87-A, Appeals Chamber Judgment, ¶ 1649 (Int’l Crim. Trib. for the Former Yugoslavia Jan. 23, 2014) (reviewing the conviction of a war crimes defendant in an international tribunal for the Yugoslav Wars). United States v. Ghailani, 733 F.3d 29 (2d Cir. 2013), offers an interesting case study. For his role in the US embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania, Ghailani was initially charged with LOAC offenses in the military commission seated at Guantanamo Bay Naval Station, Cuba. Then, the Obama Administration dismissed those charges and tried him for violations of terrorism-related federal laws instead.

5. Baxter, “Some Existing Problems in Humanitarian Law,” paper presented at the Int’l Symp. of Humanitarian L. 2 (Brussels, 1974).

6. Princz v. F.R.G., 26 F.3d 1166, 1182 (D.C.Cir. 1994); Rupprecht and Kownig, eds., Global Perspectives on the Holocaust: History, Identity, Legacy 299 (Cambridge Scholars 2015) (“An understanding of the Nazi concentration and death camp system can add to our knowledge of genocide by . . . show[ing] us how a regime dedicated to mass murder mobilized all its resources for the purpose of feeding the demands of an industry that had been deliberately assigned the tasks of incarceration, degradation, and annihilation.”).

7. Netflix’s Operation Finale offers an in-depth portrayal of this event, and the BBC TV drama The Eichmann Show does a fantastic job of portraying the trial and its coverage. Meanwhile, the Netflix show Tokyo Trial offers a unique portrayal of how international law scholars and jurists approached these jurisdictional questions in the post-war tribunals. As to the legal implications of Eichmann’s seizure, Israel immediately came under heavy criticism for seizing him on Argentinian soil without the state’s consent, and Eichmann argued that this violation of his fundamental rights invalidated the case against him. See Randall, “Universal Jurisdiction Under International Law,” 66 Tex. L. Rev. 785, 813 (Mar. 1988). Israel and Argentina eventually resolved their diplomatic crisis, with Israel apologizing for the incursion and Argentina waiving its protest of Israel’s jurisdiction over Eichmann. Id. Even under US law, an “irregular” seizure of a defendant from another jurisdiction does not violate their due process rights or entitle them to a dismissal of their case, as long as their rights are respected once they are in the prosecution’s jurisdiction. Id. at n.176 (citing Frisbie v. Collins, 342 U.S. 519 (1952) (domestic interstate seizure), reh’g denied, 343 U.S. 937 (1952) and Ker v. Illinois, 119 U.S. 436 (1886) (international seizure)).

8. Randall, supra note 7 at 811.

9. For a more in-depth discussion of his life, capture, and trial, as well as an exploration of defense of superior orders, also known as “the Nuremberg Defense,” see “Genocide: The Trial of Adolf Eichmann and the Quest for Global Justice,” 8 Buff. Hum. Rts. L. Rev. 45, 74 (2002) (explaining that his defense did not defend or rationalize Nazi policies, and instead denied legal responsibility for genocide on the grounds that he was only an administrative adjunct who, with supposedly no autonomy of his own, believed he was obligated to obey superior orders). See also id. at 101 (noting the verdict that Eichmann was more than a “mere cog” in a Nazi machine propelled by others and was in fact one of the principal accessories who propelled the machine).

10. Id. at 105.

11. Id. at 101 (overviewing the argument against jurisdiction that Eichmann’s defense team offered).

12. Id. at 108.

13. Id. at 48, 108.

14. Id. at 107.

15. Id. at 110–11.

16. Randall, supra note 7 at 811.

17. Id.

18. For the unacquainted, the Jedi are a group of people and aliens in Star Wars who are “Force sensitive.” Depending on who you ask, the Force is a supernatural power, the ultimate plot contrivance, or a mix of both. The Jedi are led by a council of Jedi masters. In the prequel trilogy, they offer their diplomatic and paramilitary services to the Galactic Republic. Once it falls, they become more of an insurgent group, leading the rebellion against the Galactic Empire in the original trilogy, and leading the resistance against the First Order in the sequel trilogy.

19. This article uses “law of war” and “law of armed conflict” interchangeably. Of the two terms, “law of armed conflict” is more technically accurate, as these laws apply in any armed conflict, even the ones that do not amount to a high-intensity war.

20. Ohlin, “The Common Law of War,” 58 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 493 (Nov. 2016).

21. Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field, Aug. 22, 1864, 22 Stat. 940 (hereinafter 1864 Red Cross Convention) (revised in 1906); Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field, art. 49, Aug. 12, 1949, 6 U.S.T. 3114, 75 U.N.T.S. 31 (hereinafter GC I); Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded, Sick, and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea, art. 50, Aug. 12, 1949, 6 U.S.T. 3217, 75 U.N.T.S. 85 (hereinafter GC II); Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War art. 22, ¶ 1, Aug. 12, 1949, 6 U.S.T. 3316, 75 U.N.T.S. 135 (hereinafter GC III); Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, art. 146, Aug. 12, 1949, 6 U.S.T. 3516, 75 U.N.T.S. 287 (hereinafter GC IV); Hague Convention with Respect to the Laws and Customs of War on Land, July 29, 1899, 32 Stat. 1803; Hague Convention Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land, Oct. 18, 1907, 36 Stat. 2277. These conventions were originally referred to as separate bodies of law (as in, “the Law of Geneva” and “the Law of the Hague,”) but they have been sewn together into one body of law by the treatises known as Additional Protocols I and II—or, more formally: Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and Relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts art. 85(5), June 8, 1977, 1125 U.N.T.S. 3 (hereinafter AP I); Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and Relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts, Jan. 23, 1979, 1125 U.N.T.S. 609 (hereinafter AP II). See Thürer, International Humanitarian Law: Theory, Practice, Context 33, 46–47 (Cambridge Univ. Press 2011).

22. AP II, art. 4(3)(c). This recruitment or use of child soldiers is by no means an isolated incident for the Jedi Order. Children often begin Jedi training when they are very young, even younger than 9-year-old Anakin, but are Jedi Younglings child soldiers? The question is beyond the scope of this article, but the author covers questions like these in a monthly “War Crimes in the Star Wars Universe” CLE.

23. This has not happened before, but if a child soldier were to commit a large-scale wartime atrocity, the international criminal law norm of seeking justice would collide with the customary legal norms in most Western systems against the criminal prosecution of children as adults.

24. Episode I does raise an interesting question about Anakin’s potential vicarious liability for letting a child engage in hostilities, however. He engineered a droid, R2D2, who then acts as his co-pilot throughout the battle depicted at the end of Episode I. As its programmer, would Anakin bear criminal responsibility for designing a weapon that would aid and abet his own child soldiery? Combatants bear personal responsibility for their own actions, and for the orders they issue, but would a drone engineer’s algorithm count as an “order”? Or would a truly autonomous droid, like R2D2, be solely responsible for its own actions? These are not questions that a court of law has had to address, but drone warfare has played a prominent role in the 2022 Russia-Ukraine war, and it is only a matter of time before truly autonomous drones make an appearance on the battlefield.

25. In scenes that have not aged well, Amidala repeatedly rejects Anakin’s romantic advances, even stating, “Please don’t look at me like that [because] it makes me feel uncomfortable,” while he persists with the romantic advances. Would she have a claim against the Jedi Order, for negligently training and negligently supervising their agent? Has Anakin knowingly created an openly hostile work environment? The answer to both questions seems to be a definite “yes.”

26. This is why genocide and crimes against humanity are often charged separately from “war crimes.” Despite being violations of the law of war, they can also take place in peacetime.

27. See Parsons, “Combatant Immunity in Non-International Armed Conflicts Past and Future,” 1 Homeland & Nat’l Sec. L. Rev. at 5 (2014).

28. Id. See also Margulies, “Networks in Non-International Armed Conflicts: Crossing Borders and Defining ‘Organized Armed Group,’” 89 Int’l L. Stud. Ser. US Naval War Col. 1, 57 (2013).

29. N.Y. Times Co. v. United States DOJ, 756 F.3d 100, 528 (2d Cir. 2014); AP I, art. 51(4) (“Indiscriminate attacks are prohibited. Indiscriminate attacks are: (a) those which are not directed at a specific military objective; (b) those which employ a method or means of combat which cannot be directed at a specific military objective; or (c) those which employ a method or means of combat the effects of which cannot be limited as required by this Protocol; and consequently, in each such case, are of a nature to strike military objectives and civilians or civilian objects without distinction.”).

30. Transcript of Oral Argument at 5, Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 542 U.S. 507 (2004) (No. 03-6696).

31. Ghaleb Nassar Al-Bihani v. Obama, 619 F.3d 1, 20 (D.C.Cir. 2010).

32. See Weinthal and Bruch, “Protecting Nuclear Power Plants During War: Implications From Ukraine,” 53 Enviro. L. Inst. 10285, 10295 (Apr. 2023) (discussing Ukraine’s efforts to inspect and gather evidence of war crimes in real time, in order to “provide the basis for enhancing accountability for Russia’s” invasion and occupation of Ukrainian territory).

33. See Dinstein, “The Defense of ‘Obedience to Superior Orders’ in International Law,” 11 Am. J. of Juris. 139 (Jun. 1966).

34. GC II, art. 50, supra note 21.

35. GC III, supra note 21.

36. Baxter, supra note 5; Smith, “Fair and Impartial? Military Jurisdiction and the Decision to Seek the Death Penalty,” 5 U. Mia. Nat’l Sec. & Armed Conf. L. Rev. 1 (2015).

37. See Zengel, “Assassination and the Law of Armed Conflict,” 134 Mil. L. Rev. 123, 131 (1991).

38. See generally Noone, “Prisoners of War in the 21st Century: Issues in Modern Warfare,” 50 Naval L. Rev. 1 (2004). The same principle applies to Vader himself, at the end of Episode III. After a prolonged lightsaber duel with his mentor Obi-Wan Kenobi, Vader ends up getting chopped in half. Arguably, he has lost the fight at that point. But at this moment, when Vader is harmless and injured, Obi-Wan walks away instead of rendering medical aid, as required under the law of war. Id. at 17 (“The law of war prohibits the willful denial of needed medical assistance to [enemy prisoners of war], and priority treatment, regardless of nationality, must be based on medical reasons.”). If Vader is found guilty of any LOAC violation, then his defense team would likely ask the tribunal to extend some mercy during the sentencing phase of his trial, in light of the fact that he is a victim of Jedi war crimes, and as a former Jedi child soldier and as a surrendered combatant who was denied medical aid.

39. GC III, art. 3, supra note 21.

40. In re Yamashita, 327 U.S. 1 (1946) (upholding the conviction of a Japanese general for failing in his duties as an army commander to stop the atrocities of his troops and finding that the law of war imposes a duty on a military commander to take appropriate measures within their power to ensure that their troops do not violate the law of war, and that commanders may be charged with personal responsibility for the failure to take such measures if troops engage in such violations).

41. Greppi, “The Evolution of Individual Criminal Responsibility Under International Law,” 81 Int’l Rev. Red Cross 531, 531–53 (Sept. 30, 1999) (tracing the doctrine of command responsibility back to a tribunal of the Holy Roman Empire in 1474, which tried an army commander for his troops’ atrocities despite his lack of participation in the atrocities and his lack of orders to carry out the atrocities). Article 28 of the Rome Statute is a modern codification of the command responsibility rule, noting that the commander is responsible for crimes “committed by forces under his or her effective command and control . . . where . . . that military commander . . . knew or . . . should have known that the forces were committing or about to commit such crimes; and that military commander or person failed to take all necessary and reasonable measures within his or her power to prevent or repress their commission or to submit the matter to the competent authorities for investigation and prosecution.” Root, “Some Other Men’s Rea? The Nature of Command Responsibility in the Rome Statute,” 23 J. Transnat’l L. & Pol’y 119, 123 (2013–14).

42. In re Yamashita, 327 U.S. at 11 (“An important incident to the conduct of war is the adoption of measures by the military commander, not only to repel and defeat the enemy, but to seize and subject to disciplinary measures those enemies who, in their attempt to thwart or impede our military effort, have violated the law of war.”). The command responsibility doctrine continues to develop, long after Yamashita. The latest case under this doctrine appears to be Bashe Abdi Yousuf v. Mohamed Ali Samantar, No. 1:04cv1360, 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 122403 (E.D.Va. Aug. 28, 2012), which concerned a terrorism trial. Id. (holding that “command responsibility does not require proof that a commander’s behavior proximately caused the victim’s injuries”).

43. This may be why the Obama Administration passed up on a GoFundMe request to build a Death Star. See Palmer, “White House Rejects Death Star Petition: Doomsday Devices US Could Build Instead,” Int’l Bus. Times (Jan. 14, 2013) (explaining that the administration rejected a petition to spur job creation by building a Death Star and stating that “the Administration does not support blowing up planets”).

44. N.Y. Times Co. v. USDOJ, 756 F.3d 100, 528 (2d Cir. 2014).