Your First Vaccine Injury Case

A Primer on Handling Claims

November 2020

Download This Article (.pdf)

This article provides the history and an overview of the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program. It offers practical guidance for practitioners to evaluate and litigate vaccine injury claims.

Vaccines are a hallmark of modern medicine. The smallpox virus, which once plagued humanity with centuries of outbreaks and a 30% fatality rate, has perished because of the smallpox vaccine.1 The novel coronavirus may be the next virus to meet its end at the hands of a vaccine. But notwithstanding their utility, vaccines can injure, and sometimes catastrophically.

After a wave of vaccine injury lawsuits nearly chased vaccine manufacturers out of the US vaccine market in the 1980s, Congress established the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP), a non-adversarial, no-fault alternative to common law tort. This article offers an overview of the VICP and guidance on how to evaluate and litigate vaccine injury claims.

How Vaccines Work

We live in a microbial world. Our immune system is locked in a constant struggle with the microbes all around us, but viruses and bacteria are as interested as we are in surviving.2 Anyone who has had a cold knows that the immune system is not always successful in this struggle. At times, it mistakes a harmless microbe as a threat—hence, seasonal allergies. At times, it mistakes a harmful microbe as no threat, leading to viral and bacterial infections.

Antibiotics are effective at killing bacteria, until they develop antibiotic resistance.3 But because viruses are much tinier and harder to target than bacteria, the best defense against them is a strong immune system.4 To that end, vaccines train the immune system to recognize a viral invasion as a threat.5 Typically, vaccines accomplish this by introducing a weakened version of the pathogen into an immune system. As more people develop immunity to that pathogen, it runs out of eligible hosts and perishes.6 This “herd immunity” helps protect immunocompromised people, whose immune systems would be overwhelmed even by the weakened vaccine version of the pathogen.7

Vaccine Safety

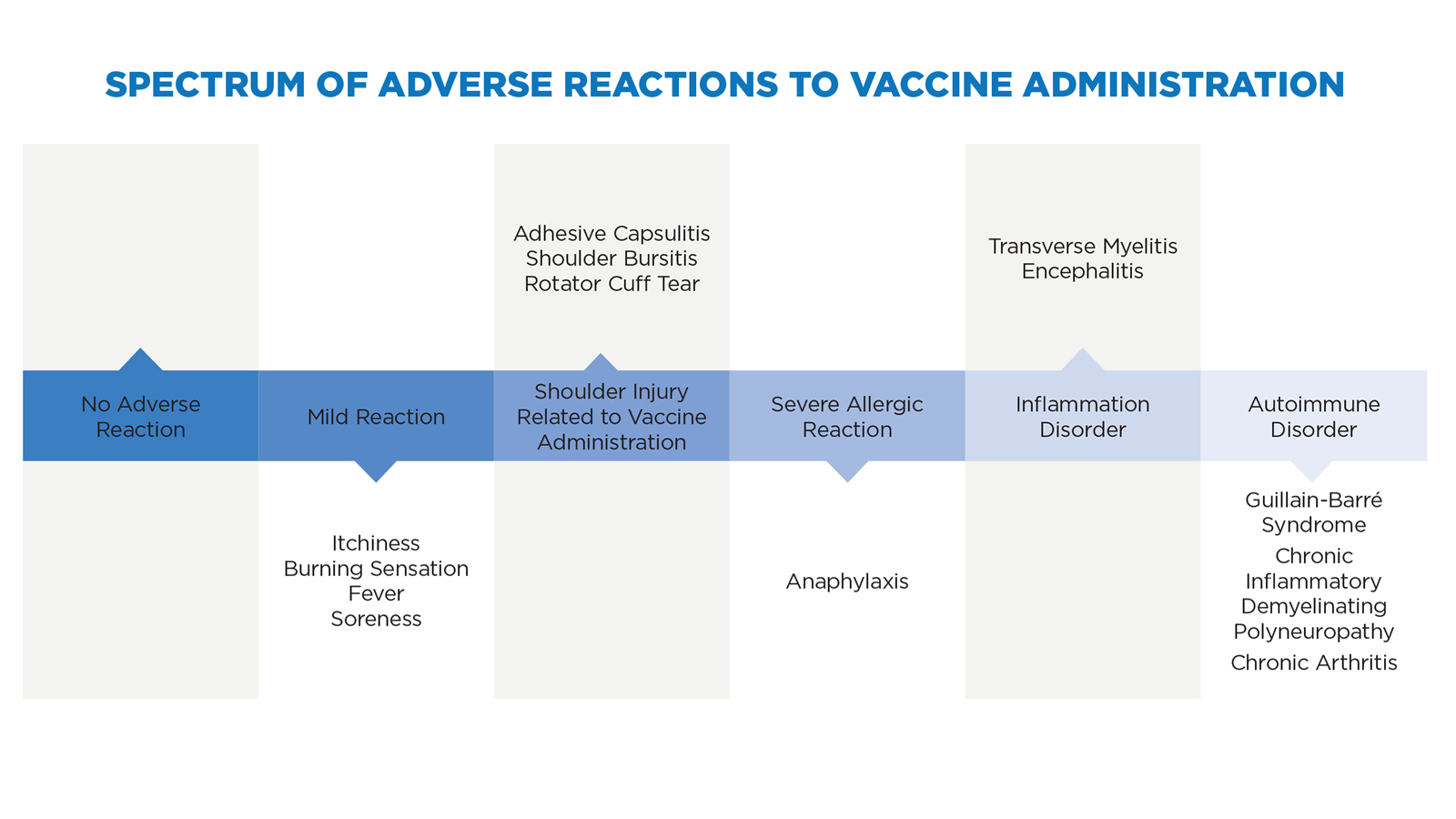

All medical intervention comes with risk, whether one is ingesting aspirin or injecting a vaccine.8 Vaccine injuries typically result from either the vaccination or from the vaccine itself. Vaccination injuries result from poorly administering an otherwise perfectly good vaccine, while vaccine injuries result when, even after the injection is correctly performed, the body responds poorly to the vaccine.

Take the main vaccine on the market, the influenza (flu) vaccine. It should be injected in the midpoint of the nondominant arm’s deltoid muscle, at a 90-degree angle.9 If the vaccinator misses that injection site or injects at a poor angle, the injection may result in inflammation that damages musculoskeletal structures, causing chronic pain and limited range of motion due to adhesive capsulitis, shoulder bursitis (frozen shoulder), or rotator cuff tear.10 Paralysis or neuropathy can also result if the injection hits a nerve.11

Even if the vaccinator correctly administers the flu shot, adverse effects might occur. Typically, these effects are merely a brief inconvenience such as a fever, or a mild allergic reaction or soreness at the injection site. These reactions are a natural result of the immune system responding to, fighting off, and remembering the injected pathogen. If a more severe adverse reaction takes place, it often occurs as a severe allergic reaction, inflammation, or autoimmune disorder.

A severe allergic reaction to vaccine ingredients, such as egg or gelatin, can result in anaphylaxis, which often presents as itchy hives or swelling of the throat.12 Vaccine-induced transverse myelitis may occur when the injection of the vaccine leads to spinal cord inflammation and nerve damage, which can present as blurred vision, weakness, paralysis, and bladder or bowel dysfunction.13 Encephalitis occurs when the immune system response to the vaccine causes brain inflammation, resulting in headaches, fatigue, and/or brain damage.14

Autoimmune disorders involve the immune system attacking itself. The autoimmune disorders that most often appear in vaccine injury cases are Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIPD), and chronic arthritis.15 GBS results from the immune system attacking its own nerve cells, leading to muscle weakness and paralysis.16 CIPD is a form of GBS that results from the immune system attacking its own myelin, leading to impaired sensory function and loss of motor coordination.17 Chronic arthritis can result if the immune system response causes joint pain and swelling.18

As severe as these disorders may be, their symptoms are amorphous and often take weeks or months to develop, making it difficult to diagnose the disorder as a vaccine-induced injury with a high degree of medical certainty.19 Starting with the first vaccine injury lawsuits, causation was and continues to be the most challenging aspect of vaccine injury litigation.

Common Law Vaccine Injury Liability

Courts first addressed vaccine injury liability in Gottsdanker v. Cutter Laboratories.20 In 1955, Jonas Salk released a polio vaccine.21 Sadly, poor manufacturing standards led to “The Cutter Incident,” in which 40,000 children who received this vaccine contracted polio and infected their families and communities.22 The resulting polio epidemic marks one of the worst pharmaceutical disasters in American history.23

Gottsdanker distinguished between vaccine efficacy and vaccine safety, noting that the case did not involve a vaccine efficacy claim that the vaccine failed to protect the vaccinee against polio.24 Such a claim would have failed.25 Instead, the petitioners presented a vaccine safety claim, alleging that the vaccine itself caused polio.26 With that distinction, Gottsdanker set the framework for manufacturer liability in vaccine injury claims.27

In 1976, an outbreak of swine flu resulted in a government swine flu program that immunized vaccine manufacturers from vaccine injury liability, created a federal vaccine injury claims process, and facilitated the quick vaccination of one-third of the adult US population.28 To boost public confidence in the shot’s safety, President Gerald Ford televised his immunization.29 By 1985, over 4,000 vaccine injury claims had been filed, alleging injuries such as Guillain-Barré syndrome.30 Even though most cases were dismissed for failure to prove a causal connection between the injury and the vaccination, the claims cost the government nearly as much as the program itself.31

The 1980s saw a wave of diphtheria/tetanus/pertussis (DTP) vaccine lawsuits based on negligence theories, public outrage over vaccine injuries, and congressional hearings on vaccine safety.32 By the mid-80s, DTP lawsuits against Lederle alleged damages exceeding 200 times the manufacturer’s total sales,33 and Connaught Laboratories found itself defending against lawsuits demanding a combined billion dollars in damages.34 In 1985, Kearl v. Lederle Laboratories expanded vaccine injury liability to new heights as the first case to permit product liability claims over vaccine injuries.35

Faced with ever-increasing liability, both in quantity and quality, vaccine manufacturers began spiking vaccine prices or leaving the market altogether.36 The very real possibility of vaccine shortages loomed on the horizon, along with the loss of herd immunity and the return of routine epidemic outbreaks.37

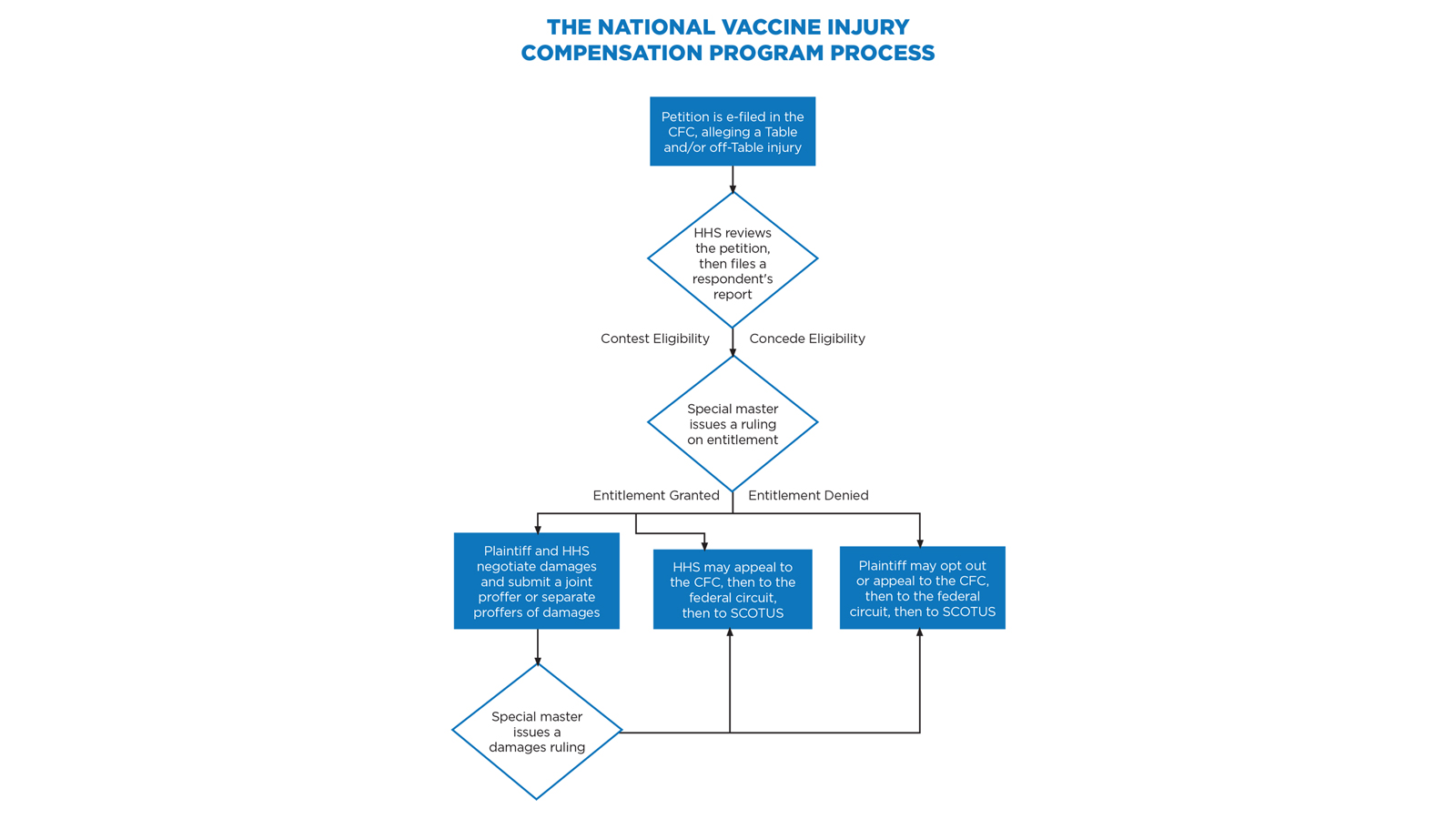

The VICP

Congress stepped in to avert the crisis with the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act of 1986,38 which established an extensive federal role in vaccine safety, development, and monitoring, and created the VICP.39 The VICP preempts virtually all vaccine injury claims in the United States, requiring that vaccine injury petitioners bring their claims to the US Court of Federal Claims (CFC).40 These claims proceed under a simplified, informal system that does not involve a jury, formal discovery process, or rules of evidence; imposes a statutory 240-day deadline for the court to issue its final ruling; and extends the promise of compensating “vaccine-injured persons quickly, easily, and with certainty and generosity.”41

A chief special master and seven associate special masters preside over these cases, with a Department of Justice (DOJ) staff attorney representing the respondent, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). A 75-cent excise tax on each vaccine dose administered in the US funds the program.42 While the CFC sits in Washington, D.C., nearly everything is filed electronically and handled telephonically. As a result, a vaccine attorney in Colorado can offer full representation to petitioners worldwide.43

Evaluating a Prospective Vaccine Injury Case

The vaccine claims process may be simplified, but strict adherence to the process is required. Disregarding the vaccine court rules and formalities can result in the dismissal of an otherwise viable case. Given the extent of the injuries often involved, a dismissal may expose practitioners to significant malpractice liability.

For this reason, practitioners should carefully review the vaccine court’s rules and guidelines (including sample forms),44 and evaluate a prospective vaccine injury claim by evaluating (1) whether the claim is timely, (2) what the medical records show, (3) whether HHS will contest entitlement, and (4) the nature and extent of damages.

Is the Claim Timely?

If a prospective vaccine-injured client walks into your office, the immediate issue to determine is whether the statute of limitations has passed or is about to pass. Petitioners must file their claim within three years of the first symptoms of injury (or, for preexisting injuries, within three years of the first significant aggravation of the injury).45 Decedents’ estates must file their claim within two years of death and within four years of any of the above-referenced injury events.46

Meeting this deadline can be daunting. The first sign of injury is often trivial and ignored until it worsens. Medical providers frequently do not suspect a vaccine injury because such injuries are so rare. Gathering and reviewing the prospective client’s voluminous medical records takes time as well. And failure to discover that the injury is vaccine-induced does not toll the statute of limitations.47

What Do the Medical Records Show?

After analyzing and addressing, if necessary, any statute of limitations concerns, the next step is to gather and review the medical records. It can take months for large hospitals to respond to medical records requests, and the novel coronavirus pandemic has further slowed response times.

When submitting a medical records request, it is important to provide sufficient identifying information. The best practice is to have the client sign your retainer agreement and a thorough HIPAA agreement that includes the client’s full legal name, date of birth, and social security number, and a scanned copy of the client’s driver’s license. Including insufficient identifying information may support a medical provider’s refusal to provide the records.

Each medical provider that your client has seen since receiving the vaccine and in the three years leading up to the vaccination must provide a copy of the entire client record. Do not let the simplified and informal nature of the process fool you; the claim is in federal court, and special masters will not hesitate to strike exhibits of medical records if they appear to be incomplete. The medical records should identify the information needed to determine eligibility under the VICP, including the vaccine at issue, the diagnosed injuries, and the date the initial symptoms arose.

HHS periodically updates a list of recognized vaccine injuries, based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations, on an HHS Vaccine Injury Table (Table).48 If a petitioner receives a vaccine listed on the Table while in the United States and then experiences an injury described in the Table within the time frame listed, causation is rebuttably presumed.49 Petitioners with Table injuries are entitled to compensation on proof that the injury is sufficiently “severe,” meaning that the symptoms have lasted over six months or resulted in death, hospitalization, or surgery.50

For claims that fall outside the Table, the petitioner must prove severity and causation by a preponderance of evidence. This requires an expert report, and HHS typically offers competing causation evidence. If the matter cannot be settled, the special master decides whether the petitioner has met the burden to prove causation.51

Even for claims that seem to be Table injuries, it is wise to argue, in the alternative, that the injury may be an off-Table injury. Under VICP’s “one petition rule,” a petitioner can file only one petition per vaccine injury.52 By claiming the injury as both on and off the Table, counsel ensures that the claim will survive even if the special master decides it does not meet Table criteria.

Will HHS Contest Entitlement?

If the medical records suggest eligibility for recovery under the VICP, whether as an on- or off-Table case, there is likely a reasonable basis to file the claim. Once you electronically file the petition and supporting documents, a physician at HHS’s Division of Vaccine Injury Compensation will review the submission.53 If the physician agrees that the evidence meets the standard for compensation, the DOJ staff attorney representing HHS will likely concede to the entitlement issue in HHS’s “respondent’s report.” This process generally takes 90 days.

However, HHS’s medical expert may decide that more evidence is necessary, or that the evidence provided already disproves the case. This can happen if the alleged Table injury does not quite fit into the Table, if the evidence does not prove the injury to be sufficiently severe, or if HHS believes it can refute causation. The author’s experience is that severity is often the weakest link that results in HHS contesting entitlement.54

Accordingly, practitioners can rely on two rules of thumb: (1) Table claims resolve more quickly, reliably, and simply than off-Table claims because the Table acts as causation per se evidence, and causation is difficult to prove;55 and (2) the more clearly the medical records prove every aspect of entitlement (whether causation is assumed or must be proven), the more likely HHS will concede the entitlement issue.

What are the Damages?

After proving entitlement to compensation, the petitioner must prove damages.56 The VICP permits four categories of damages: past medical expenses, anticipated future medical expenses, lost earnings, and pain and suffering (the last of which is capped at $250,000).57 The VICP covers only out-of-pocket medical expenses, which means that hospitals and health insurance providers are not entitled to any portion of recovery.58

Past medical expenses and lost earnings are generally quantifiable, as they are based on out-of-pocket medical bills,59 paystubs, or W9s for petitioners who are self-employed or lack traditional paystubs. Future life care planners can offer opinions on anticipated future medical expenses, with the petitioner’s planner offering one estimate and HHS, if it chooses to contest the estimate, offering an alternative (lower) estimate.60 There is no cap on anticipated future medical expenses, and depending on the injury, this may comprise the lion’s share of a large award.

Pain and suffering is an ephemeral concept, but the CFC’s online database of past damages awards in vaccine injury cases helps the parties (or, failing that, the special master) reach an amount consistent with comparable cases.61 When evaluating pain and suffering, two rules of thumb are (1) shoulder injuries normally involve less pain and suffering than autoimmune disorders, and (2) higher amounts of medical expenses and lost wages generally justify a higher pain and suffering calculation.

Attorney Fees

Petitioners pay no attorney fees.62 Instead, the VICP reimburses all attorney fees and expenses in a payment separate from the petitioner’s compensation. This usually occurs after the case concludes, but interim payments are possible for cases that involve a substantial amount of time and work.63 Even if a case is dismissed, attorneys are entitled to recover fees so long as they had a reasonable basis to bring a good faith claim.64 The special master determines the amount of the hourly fee, based on the fee schedule that the Office of the Special Masters updates annually.65

Dealing with Unsatisfactory Results

If either party is unsatisfied with a special master’s ruling, that ruling is reviewable by a CFC judge, then by the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, and then by the US Supreme Court.66 The CFC may set aside findings of fact and conclusions of law if the special master’s determination was arbitrary and capricious, an abuse of discretion, or not in accordance with law.67 The federal circuit reviews questions of law de novo, but applies to factual disputes the same standards of review as the CFC.68 The US Supreme Court has granted three petitions in vaccine injury cases.69

After a petitioner has exhausted his or her administrative remedies through the VICP, the petitioner can pursue a regular personal injury case.70 Very few petitioners do so, however, as the Vaccine Act significantly limits civil claims against vaccine administrators and manufacturers.71 Manufacturers are immune from punitive and exemplary damages, as well as from design-defect claims and defective warning claims.72 Accordingly, unless a party can confidently prove that the vaccine manufacturer failed to comply with federal regulations, engaged in fraud, or wrongfully withheld information regarding vaccine approval, safety, or efficacy, pursuing a civil claim is likely inadvisable.

Overall Trends

The VICP has seen over 20,000 claims since its inception.73 Over 6,500 claims succeeded, receiving a collective $4.3 billion in payments, which is roughly $660,000 per case.74 The vaccines most often at issue have been the flu vaccine (4,057 claims out of 1.5 billion doses), the Tdap vaccine (514 claims out of 250 million doses), and the HPV vaccine (326 claims out of 111 million doses), with all remaining vaccines seeing fewer than 300 claims over the past 30 years.75 Overall, out of one million vaccinations, one person receives an injury that the VICP compensates.76

Since 2018, roughly 1,200 VICP petitions have been filed each year, which is twice the rate seen in 2005 to 2015.77 If the novel coronavirus pandemic creates a surge in demand for the flu vaccine and the eventual coronavirus vaccine, 2021 may witness a surge of petitions. While surges can delay the processing of claims, the VICP has handled surges before and has never run out of funds.78 Nearly $4 trillion sits in the Vaccine Trust Fund today.79 The interest payments alone are often enough to cover all claims in a year.80

Death accounts for roughly 14% of VICP claims. Counterintuitively, only 2% of claims are Table claims.81 This low percentage may suggest that the Table has failed to keep pace with the rapidly developing vaccine market, but it may instead be the result of dubious claims. For instance, over 5,600 autism claims have been filed in the VICP, and this author is not aware of any successes.82

Petitioners’ success rates vary wildly, depending on the special master who is randomly assigned to the case and on the experience of the petitioners’ counsel, with just 32% of petitioners succeeding if paired with certain special masters and petitioners’ counsel, and 72% of petitioners succeeding if paired with another group of special masters and petitioners’ counsel.83 The reason behind this variance is unclear, but high success rates may result from successful attorneys selectively bringing only the most meritorious cases. The HHS staff attorneys may also play a role, especially if they approach the case in a more adversarial manner than the VICP might have intended.84

Seven out of 10 claims settle and require minimal special master involvement.85 Attorney fees are generally $22,052 in successful cases, and $14,053 in unsuccessful cases.86 When the court issues its VICP payment, 86% of that payment goes directly to the petitioner, with the remainder consumed by transaction costs.87 This compares favorably to auto collision cases, in which transaction costs are closer to 50%.88

The statutory requirement to adjudicate VICP cases within 240 days is one of the most attractive features of the program. Unfortunately, just 4.5% of claims resolve within this deadline.89 Between 1999 and 2014, the VICP’s average adjudication time was 5.5 years.90 There are no consequences to exceeding the 240-day requirement. This lengthy process reflects the difficulty of proving causation in off-Table claims, but in this author’s experience, Table claims typically resolve within 240 days, with little to no transaction costs or adversarial posturing from HHS.

The VICP’s Impact

The VICP has had an immense impact on the American legal landscape by serving as an example of how certain types of claims may be streamlined and managed. Florida, Illinois, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and an ever-growing list of states have proposed the creation of health courts to handle medical malpractice claims as the VICP handles vaccine injury claims.91 This reform du jour sees broad support from the medical community and the public alike.92

The success of this reform remains to be seen, but it is clear why VICP’s successes have encouraged continued experimentation. By indemnifying vaccine manufacturers and creating a simplified legal proceeding for vaccine injury victims, the VICP has struck a careful balance between maintaining vaccine supply, encouraging vaccine demand, and taking care of the one-in-a-million cases where a vaccine causes serious harm.

In large part, the VICP has revitalized the vaccine industry. Once at the brink of collapse in the 1980s, its rate of growth is now double that of pharmaceuticals.93 The effect has been more than apparent in our everyday lives. In 1989, for instance, children received six vaccines by age 2; today, that number stands at 27.94

Fear of the novel coronavirus pandemic may shake the industry even further. If a surge of Americans takes the flu vaccine, and the eventual coronavirus vaccine, Colorado attorneys may come across a corresponding surge of potential vaccine injury cases.

Conclusion

Vaccine safety is an ongoing concern, which is currently heightened with the potential for a coronavirus vaccine. The VICP affords an informal process to resolve claims for vaccine injuries, but the process has strict substantive and procedural requirements. Practitioners undertaking representation of VICP claimants must heed these requirements to ensure the best outcomes for their clients.

Related Topics

Notes

1. CDC, Smallpox, https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/index.html.

2. Villarreal, “Are Viruses Alive?,” Scientific American (Aug. 8, 2008), https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/are-viruses-alive-2004.

3. Pearsall III, “The Bacterial Renaissance: A Supply-Side Answer to the Icarus Paradox of Antibiotic Usage Undermining Its Own Usefulness,” 37 J. Leg. Med. 133–43 (2017) (exploring how and why the overuse of antibiotics has led to a resurgence in antibiotic-resistant bacteria and offering solutions to revitalize the antibiotic marketplace).

4. Andre et al., “Vaccination greatly reduces disease, disability, death and inequity worldwide,” 86 Bull. World Health Org. 140, 141 (Feb. 2008), www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/86/2/07-040089.pdf.

5. Id.

6. Id. at 142.

7. Id.

8. Li et al., “Age-specific risks, severity, time course, and outcome of bleeding on long-term antiplatelet treatment after vascular events: a population-based cohort study,” 390 The Lancet 100093 (July 29, 2017) (suggesting that aspirin contributes to 3,000 deaths per year in the United Kingdom); Chen et al., “The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS),” 12 Vaccine 542 (1994) (noting that CDC and US Food and Drug Administration experts agree it is unrealistic to expect any vaccine to be perfectly safe or effective).

9. Wash. State Dep’t of Health, CDC Intramuscular Vaccination Infographic, https://www.doh.wa.gov/ForPublicHealthandHealthcareProviders/PublicHealthSystemResourcesandServices/Immunization/LinksforProviders.

10. These are known collectively as shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA) injuries.

11. The good news is that vaccine-induced nerve injuries are easy to identify, as nerve damage often results in an immediate burning pain at the injection site.

12. Nichols v. Sec’y of Health and Human Servs., 2018 U.S. Claims LEXIS 206 at 17 (Fed. Cir. 2018).

13. White v. Sec’y of Health and Human Servs., 2019 U.S. Claims LEXIS 2223 at 13–25 (Fed. Cir. 2019).

14. Al-Uffi v. Sec’y of Health and Human Servs., 2017 U.S. Claims LEXIS 464 at 8–10 (Fed. Cir. 2017).

15. Health Res. and Servs. Admin., National VICP Monthly Statistics Report at 5 (Apr. 1, 2020) (hereinafter VICP Statistics Report).

16. Fedewa v. Sec’y of Health and Human Servs., 2020 U.S. Claims LEXIS 623 at 7 (Fed. Cir. 2020).

17. Patel v. Sec’y of Health and Human Servs., 2020 U.S. Claims LEXIS 913 at 10–12 (Fed. Cir. 2020).

18. C.P. v. Sec’y of Health and Human Servs., 2019 U.S. Claims LEXIS 1527 at 15–18 (Fed. Cir. 2019).

19. Reitze, “Federal Compensation for Vaccination Induced Injuries,” 13 B.C. Envtl. Aff. L. Rev. 169, 186 (1986). There may also be a fear among many physicians of ruining their professional reputation by making a vaccine injury diagnosis, reporting a vaccine injury, or testifying in a vaccine injury case. Levin, “Witnesses for Petitioners Are Often Tough to Find,” L.A. Times (Nov. 29, 2004).

20. Gottsdanker v. Cutter Labs., 6 Cal. Rptr. 320 (Cal. Dist. Ct. App. 1960).

21. Offit, “The Cutter Incident, 50 Years Later,” 352 New Eng. J. Med. 1411 (Apr. 7, 2005).

22. Id.

23. Id.

24. Gottsdanker, 6 Cal. Rptr. at 325–26.

25. Id.

26. Id.

27. See also Reyes v. Wyeth Labs., 498 F.2d 1264 (5th Cir. 1974) (involving an infant paralyzed by the polio vaccine and reasoning that between victims and manufacturers, the latter should bear the loss when catastrophic injury occurs). Other courts took the opposite approach and barred vaccine injury lawsuits. See Shackil v. Lederle Labs., 561 A.2d 511 (N.J. 1989) (dismissing the vaccine injury claim on public policy grounds that such suits discourage vaccine innovation and development). Problematically, where granting liability jeopardized vaccine supply by chasing vaccine manufacturers out of the vaccine market, denying liability jeopardized vaccine demand by discouraging people from risking vaccine therapy.

28. National Swine Flu Immunization Program of 1976, Pub. L. No. 94-380, § 2, 90 Stat. 1113, 1115 (codified as amended at 42 USC § 247b).

29. Reitze, supra note 19 at 179.

30. Id. at 181.

31. Id. at 184–85.

32. Allen, Vaccine: The Controversial Story of Medicine’s Greatest Lifesaver 251–55 (W.W. Norton & Co. 2007).

33. Vaccine Injury Compensation: Hearings on H.R. 5810 Before the Subcomm. on Health and the Env’t of the H. Comm. on Energy and Commerce, 98th Cong. 229 (1984).

34. Funding of the Childhood Vaccine Program: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on Select Revenue Measures of the H. Comm. on Ways and Means, 100th Cong. 16, 104 (1987).

35. Kearl v. Lederle Labs., 218 Cal. Rptr. 453, 455 (Cal. Ct. App. 1985).

36. H.R. Rep. No. 99-908 at 6 (1986), reprinted in 1986 U.S.C.C.A.N. 6344, 6347.

37. Id. at 7.

38. 42 USC §§ 300aa-1 to 300aa-34.

39. H.R. Rep. No. 99-908 at 1–2.

40. Kalinowski, “The House Built On a Hillside: The Unique and Necessary Role of the United States Court of Federal Claims,” 23 Tex. Rev. Law & Pol. 541 (2019) (exploring what the CFC does and explaining why Congress vested jurisdiction over the VICP in the CFC instead of dispersing it across the federal district courts).

41. H.R. Rep. No. 99-908 at 1; Shalala v. Whitecotton, 514 U.S. 268, 269 (1995) (stating that the VICP’s goal is to establish “a scheme of recovery designed to work faster and with greater ease than the civil tort system.”).

42. 26 USC § 4132(a)(1) (defining “taxable vaccine” for the purposes of the Vaccine Act’s excise tax).

43. The CFC maintains a list of attorneys in each state who are willing to accept vaccine injury claims, http://www.uscfc.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/Vaccine%20Attorney%20List%209.1.2020.pdf.

44. http://www.uscfc.uscourts.gov/vaccine-programoffice-special-masters.

45. 42 USC § 300aa-16(2).

46. 42 USC § 300aa-16(3).

47. Cloer v. Sec’y of Health and Human Servs., 654 F.3d 1322, 1341 (Fed. Cir. 2011) (finding that ignorance of the causal link between an injury and the administration of a vaccine does not equitably toll the Vaccine Act).

48. 42 CFR § 100.3.

49. 42 USC § 300a-14; 42 CFR § 100.3(a); W.C. v. Sec’y of Health and Human Servs., 704 F.3d 1352, 1356 (Fed. Cir. 2013).

50. 42 USC § 300aa-11(c)(1)(D).

51. VICP rulings may be illuminating to personal injury attorneys in general, as the reasoning and evidence used to prove causality in such challenging circumstances may be applicable to any injury. See Greene v. Sec’y of Health and Human Servs., 136 Fed. Cl. 445 (Fed. Cl. 2018) (vacating the special master’s decision that the vaccine injury claim failed for insufficient causality evidence and remanding for further consideration).

52. U.S. Ct. Fed. Claims Vaccine R. 2(a) (“Only one petition may be filed with respect to each administration of a vaccine.”). This rule has recently been relaxed for pregnant women so that a claim against the same vaccination can be brought on behalf of the child separately from the claim brought on behalf of the pregnant woman. 21st Century Cures Act, § 3093(c) (amending 42 USC § 300aa-11(b)(2)).

53. Evans, Update on Vaccine Liability in the United States: Presentation at the National Vaccine Program Office Workshop on Strengthening the Supply of Routinely Recommended Vaccines in the United States, 42 Clinical Infectious Diseases S130, S131 (2006).

54. Vaccine injury victims often try to return to normal life before the six-month mark, at which point their medical records grow sparse. This is an especially frequent issue in shoulder-related injuries, which often match Table criteria but later subside and do not require hospitalization or surgery. Additional physical therapy or treatment may provide the necessary evidence that the petitioner continues to suffer from symptoms of their injury after six months.

55. Inst. of Med., Vaccine Supply and Innovation at 155 (1985) (predicting that the “difficulty of proving or disproving a causal relationship between a given vaccine and a particular injury suggest[s] that . . . outcomes will depend on who is required to carry the burden of proof.”).

56. Office of Special Masters, Guidelines for Practice Under the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program at 5 (rev. Apr. 24, 2020) (hereinafter OSM Guidelines), https://www.cofc.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/Guidelines-4.24.2020.pdf.

57. Id. at 56–57.

58. Id. at 56.

59. For instance, the author handled a case where the health insurance provider did not cover ambulance transportation from one hospital to another, even though the client needed transportation from a small hospital to a larger one that specialized in GBS treatment. This lack of coverage left the client with a nearly $10,000 bill.

60. Id. at 55–60.

61. Id. at 60. See US Court of Federal Claims Opinions, https://www.uscfc.uscourts.gov/aggregator/sources/7.

62. 42 USC § 300aa–15(e)(3) (“No attorney may charge any fee for services in connection with a petition” under the VICP).

63. Cruz v. Sec’y of Health and Human Servs., 2020 U.S. Claims LEXIS 534 at 5–6 (Fed. Cir. 2020).

64. 42 USC § 300aa-15(e).

65. A fee of about $200 per hour is typical for new attorneys, while a fee of about $400 can be expected for more experienced practitioners.

66. 42 USC § 300aa-12(f).

67. Porter v. Sec’y of Health and Human Servs., 663 F.3d 1242, 1249 (Fed. Cir. 2011). Specifically, findings of fact are reviewed under an arbitrary and capricious standard, conclusions of law are reviewed under a “not in accordance with law” standard, and discretionary rulings are reviewed under an abuse of discretion standard. Id.

68. Id.

69. Sebelius v. Cloer, 569 U.S. 369 (2013); Bruesewitz v. Wyeth LLC, 562 U.S. 223, 224 (2011); and Shalala, 514 U.S. at 272–73.

70. 42 USC § 300aa-21.

71. Bruesewitz, 562 U.S. at 248 (citing Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae Supporting Respondents at 28 (“Department of Justice records indicate that 99.8% of successful Compensation Program petitioners have accepted their awards, foregoing any tort remedies against vaccine manufacturers.”)).

72. 42 USC § 300aa-22(b) and (c).

73. VICP Statistics Report, supra note 15 at 5.

74. Id. Of course, this average does little to predict the outcome of any given case, as a senior citizen with a temporary shoulder injury will receive a fraction of what a child paralyzed with GBS will receive.

75. Id. at 2–3.

76. Id. at 1.

77. Id. at 5.

78. See, e.g., VICP Statistics Report, supra note 15 at 1987–2020.

79. HHS, Vaccine Injury Trust Fund Trial Balance at 6 (Apr. 1, 2020 through Apr. 30, 2020). See https://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/tfmp/vaccomp/vaccomp.htm.

80. Levin, “Vaccine Injury Claims Face Grueling Fight; Victims Increasingly View U.S. Compensation Program As Adversarial and Tightfisted,” L.A. Times (Nov. 29, 2004).

81. US Gov’t Accountability Office, Gao-15-142, Vaccine Injury Compensation: Most Claims Took Multiple Years And Many Were Settled Through Negotiation 2, 20 (2014) (hereinafter GAO Report), https://www.gao.gov/assets/670/667136.pdf.

82. Binski, “Balancing Policy Tensions of the Vaccine Act in Light of the Omnibus Autism Proceeding: Are Petitioners Getting a Fair Shot at Compensation?,” 39 Hofstra L. Rev. 683, 701 (2011).

83. See, e.g., Ridgway, “No-Fault Vaccine Insurance: Lessons from the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program,” 24 J. Health Pol. Pol’y & L. 59, 66 (1999); OSM Guidelines, supra note 56 at 4 (granting wide latitude to special masters in adjudicating claims).

84. See, e.g., Johnson et al., “Use of Expert Testimony, Specialized Decision Makers, and Case-Management Innovations in the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program” at 44 (Fed. Judicial Ctr. 1998) (citing several special masters who complained that certain staff attorneys “over-litigat[e]” and make the VICP process more adversarial than it was meant to be); Levin, supra note 80 (stating that HHS has threatened to appeal vaccine rulings in favor of the petitioner to encourage a confidential settlement that would shield the evidence from future comparable cases).

85. VICP Statistics Report, supra note 15 at 1.

86. Ridgway, supra note 83 at 74. This discrepancy may suggest that attorney fees for unsuccessful petitioners are docked for being unsuccessful, but more likely it results from the fact that unsuccessful claims resolve sooner and involve fewer hours than successful ones.

87. Detailed Information on the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program Assessment, Section 1.5, Expectmore.gov, http://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/omb/expectmore/detail/10003807.2005.html, archived at http://perma.cc/XWK3-NMSK. .

88. Hensler et al., “Trends In Tort Litigation: The Story Behind The Statistics” at 29 tbl. 4.1 (Rand Inst. for Civil Justice 1987).

89. Weiss et al., “AP IMPACT: ‘Vaccine Court’ Keeps Claimants Waiting,” Associated Press (Nov. 17, 2014), https://apnews.com/article/af3ac36a464440858a743ac5c4929bec.

90. GAO Report, supra note 81 at 10 fig. 1.

91. Farrow, “The Anti-Patient Psychology of Health Courts: Prescriptions from a Lawyer-Physician,” 36 Am. J.L. & Med. 188, 193 n.26 (2010).

92. PR Newswire Press Release, Common Good, Nationwide Clarus Poll Reveals that a Large Majority of U.S. Voters Think Legal System Increases Cost of Health Care (May 29, 2012), http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/nationwide-clarus-poll-reveals-that-a-large-majorityof-us-voters-think-legal-system-increases-cost-of-health-care-155365335.html (finding that 66% of respondents favored health courts); Am. Med. Ass’n, Medical Liability Reform Now! The facts you need to know to address the broken medical liability system 29 (2020 ed.) (“the AMA supports the testing and evaluation of health court pilot projects as an innovative way to address the medical liability problem”).

93. Kaddar, Senior Adviser, World Health Org., Address: Global Vaccine Market Features and Trends at 4 (Jan. 16, 2013).

94. Compare Iskander et al., “Data mining in the US using the vaccine adverse event reporting system,” 29 Drug Safety 375, 381 (2006) with CDC, Recommended Immunization Schedule for Children and Adolescents Aged 18 Years or Younger at 2 (2017).

Vaccine injuries typically result from either the vaccination or from the vaccine itself. Vaccination injuries result from poorly administering an otherwise perfectly good vaccine, while vaccine injuries result when, even after the injection is correctly performed, the body responds poorly to

the vaccine.

Section of the Table Relating to Seasonal Flu Vaccines

| Vaccine |

Injury |

Timeline |

| Seasonal influenza vaccine | Anaphylaxis | Within 4 hours |

| Shoulder injury related to vaccine administration | Within 48 hours | |

| Vasovagal syncope | Within 1 hour | |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | 3 to 42 days |