Athens’ Sin Against Philosophy

March 2023

Download This Article (.pdf)

Scene 1—A Trip Imagined

“What are you reading, Grandpa?” Jussi asked as he skidded to a stop and jumped off his bike.

Hiski had taken up reading outside since the weather turned warm. He sat on his wooden porch in the old wooden rocker, warming his aging muscles in the sun.

“About Athens’ sin against philosophy,” Hiski said with disgust edging his voice.

“Their sin? What’d they do?” Jussi’s eyebrows peaked with curiosity at the mention of a sin against philosophy. These discussions of philosophy frequently turned into adventures.

Hiski sucked in deeply on his pipe. “It makes me a bit angry to think about.” He blew out deeply, exhaling slowly to calm himself.

“They murdered him,” he whispered to himself. “Our father, Socrates.”

Jussi knew that Hiski would take several minutes to get control of himself, so he went inside the small trailer to peek into the fridge. Usually Hiski was meticulous, with everything in its proper place. He was even more than meticulous; he was obsessive about order and cleanliness. But today the place was a mess. “Well not really a mess,” Jussi thought to himself. “More like scattered.” Books were lying haphazardly on the floor, counters, and chairs, like they had been tossed aside after a quick inspection. Notes in Hiski’s perfectly squared writing were strewn over the tops of the books.

“I wonder what he was looking for,” Jussi said aloud to himself while pulling an orange pop from the fridge.

“Jussi,” Hiski spoke in that deep baritone he saved for moments he needed authority, “pour me a glass of scotch and come out here. I need to talk to you.”

Jussi knew exactly what to do. Pour from the bottle on the counter by the bookshelf, pour it into the smoky grey glass that Hiski kept sitting next to the bottle, and fill the glass one-third full, no more, no less. Add one ice cube, and only one. Jussi once got a 20-minute lecture on properly appreciating the simple things in life when he added three ice cubes to the glass, because colder must be better he had thought. Grabbing his soda, Jussi carried the scotch outside and handed it to his grandpa.

“Kiitos,” Hiski said, speaking Finnish, while staring down at the weathered deck beneath his feet. He moved back and forth slowly in the rocker, the deck creaking beneath him. A low rumbling came from his chest. Jussi had heard that sound before and it meant his grandpa was upset. Really upset.

“Just sit with me for a while, Jussi-poika. Your presence helps.”

Hiski rocked and Jussi sat square legged taking sips from the bottle in his hand. Hiski finally breathed in deeply and said, “It is important that you understand Athens’ sin so you can help prevent it in the future.”

“Me?”

“You never know what the future holds, my boy. You never know, so you must prepare.”

“A trip, Grandpa?” Jussi asked with excitement growing in him.

Hiski heard the new tone in his grandson’s voice. Raising his eyes to Jussi’s face, and with a grin beginning to turn up the corners of his mouth, he said, “A trip, my boy. A trip. Can you spare the courage?”

Hiski knew the answer before it even came out.

“Of course, Grandpa. A trip!”

Hiski smiled. He knew Jussi loved their trips to the past.

“But should we clean up the mess inside before we leave?” Jussi asked.

A blackness creased the edges of Hiski’s eyes, just enough for Jussi to note, and then disappeared. “Just leave it, Jussi. I found what I was looking for.”

“What’s that?”

“The plan for Socrates’s escape!”

Scene 2—The Trip Back

“Let’s see if we can get it right this time, Jussi. One leap, tip backward, and then we are off.”

Jussi ran toward the chair and leapt hard into Hiski’s lap. The momentum tipped the chair backward, but it kept tipping, never falling to the floor. They began spinning round and round and round until the black circles appeared. The Doppler effect, Hiski had told him after their second trip. They spun until Jussi couldn’t remember any more. And then he heard his grandpa’s voice.

“Up Jussi, get up.” Hiski grabbed Jussi’s shoulder and rolled him onto his back. “You always pass out.”

“I’m sorry, Grandpa—it’s the spinning.”

“It will get better soon enough.”

Jussi wondered how Hiski knew this, but he believed the words his grandpa spoke. Jussi sat up and looked around.

“We’re in the middle of a field, Grandpa. A wheat field.”

“Obviously, my boy. We couldn’t very well land in the middle of the city without raising suspicions, now could we?”

“What city?”

“Athens, of course. Now get up. And put this on,” Hiski said, handing Jussi a single piece of clothing.

Jussi knew better than to question, so he stripped off his clothes and pulled the cloth over his head. It was a single covering that hung down to his knees.

Hiski handed him a belt. “Put this on, around your waist.”

“Grandpa, this looks like a dress!”

“Yes, it does. It’s called a tunic,” Hiski said while pulling his own tunic on. “And put on those sandals next to you.”

“Where did you get them?”

“While you were sleeping, that gentlemen right over there brought them for us,” Hiski said, pointing behind Jussi to an elderly man sitting on a large stone.

Jussi turned around, inspected the man, then nodded.

“Pleased to have you here, Jussi,” the man said in Greek. “Hiski has told me much about you.”

“When?” Jussi wondered. There was much about Hiski he didn’t know, Jussi thought to himself.

“What’s that language?” Jussi asked Hiski, not even wondering why he understood it. He couldn’t explain it, but he always understood the local language when they spun through time.

“Attic,” Hiski responded. “A dialect of Greek, spoken in Athens.”

“The language of Socrates and Plato,” Jussi whispered in awe.

“Yes, my boy. We are here in Athens at the time of Socrates’s trial.”

“Who’s that man?”

“Socrates’s best friend, Crito. He is here to help us. Together we are going to try and free Socrates.”

“Just us?”

“No, there are others. But not many. Come now, let’s go.”

Leaving their clothes in a sack by the rock Crito was sitting on, they turned east and followed Crito into the city.

Scene 3—Meeting Socrates

Crito led Hiski and Jussi through the walls of Athens and into the marketplace.

“This is the agora,” Crito whispered to them. “We will find Socrates in the northwest corner, near the court. He is to be charged and tried today. So you came just in time.”

They worked their way through the crowd, Crito leading, Hiski following, and Jussi trying to keep up with the two old men.

“They may be old,” Jussi thought to himself, “but they sure can move quickly when they want to.”

Crito kept heading northwest, even though many men tried to stop them and engage Crito in conversation. By the way the men greeted him, it appeared to Jussi that Crito was well known in Athens, even important.

After much effort, they approached the ancient hall of justice. “The court is actually three buildings set in a triangle configuration,” Crito explained to them. “Socrates is to be tried in Law Court C,” Crito pointed toward the large rectangular hall on the right. “Law Court A is the large, marbled colonnade over on the left. It is reserved for trials with unusually large juries. Law Court B is the same size as C,” Crito explained, while directing their gaze to each individual building. “We should head over to the right.”

Walking over to Law Court C, Crito’s arm lifted and pointed toward an old man standing with a much younger man in front of the courthouse. “There is Socrates.”

Jussi looked intently at the father of Western philosophy, and he couldn’t help himself. “He’s so ugly!”

“Jussi!” Hiski quickly admonished.

Crito threw his head back as a laugh exploded from his chest. “It’s okay, Hiski,” he explained when he got himself under control. “I have known Socrates for almost 70 years and I can tell you he was the ugliest kid I ever saw, and he grew into the ugliest man I have ever seen. Look at him: he is short, thick through the middle, a wrinkled face with a large nose, and that nose sits on the largest head the gods have ever made. Zeus would be proud to have that weight sitting on his shoulders.”

Hiski grinned at Jussi but shook his head slightly to remind Jussi that this wasn’t an invitation to continue with such observations.

“But let me tell you something, my young friend,” Crito said, putting his hand on Jussi’s shoulder, “It is fortunate for us and for the world to come that the gods made him with such a large head. Because inside that ridiculous skull lies the largest brain the gods have ever created. We Athenians are lucky to lay claim to him. And from what Hiski tells me, so is the rest of the world.”

Jussi again looked at his grandpa, wondering what else he didn’t know about this man.

Crito took Jussi’s arm and steered him over to where Socrates was still conversing with the young man. As they approached, Socrates turned and greeted them. “Ah, my friends Crito and Hiski. And you must be Jussi. Hiski said you might be coming. I am so happy to finally meet you.”

“M-me too,” Jussi stammered.

Bending down to look Jussi in the eyes, Socrates whispered in his ear, “Pay attention to my conversation with this young man. You might learn something important.”

Standing back up, Socrates introduced the new arrivals to the young man. “Meet my good friend Euthyphro. He is a priest and an expert on religious rites that honor and benefit the gods. He is at the courts to bring charges against his own father for manslaughter.”

Scene 4—The Argument with Euthyphro

Jussi choked back his outrage and fought the rising urge to comment on Euthyphro’s actions. Before he could speak Hiski put a firm hand on his shoulder and squeezed.

“We were talking about piety,” Socrates reminded Euthyphro. And turning to the new arrivals, he said, “I think you would use the term righteousness. Yes, that fits better in your language.”

“Yes, yes, yes,” Euthyphro replied. “I have an excellent understanding of all things that are pious, being a priest and all.”

“Then tell me, my young friend,” Socrates replied, “what things are pious?”

“Well, that is easy. Prosecuting a murderer like my father is pious.”

“Most Athenians would disagree, I think,” Crito added from long experience.

“Crito is right, I am afraid,” Socrates continued. “But that is of no matter, because you didn’t answer my question. I don’t want to know what specific actions are pious, but what is the characteristic that makes all individually pious acts pious? Let me rephrase my question: What is the one thing in which all individual pious acts participate that allows you to then call them pious?”

“You are a silly man, Socrates, because you ask questions that make no sense.”

“Well let me try again, and I apologize for my lack of knowledge. Surely there is one thing that allows you to call all pious acts pious, and one different thing that allows you to call all impious acts impious. Let’s call these things the forms of piousness and impiousness, or the models from which all such acts are simply copies. Do you agree?” asked Socrates.

“Yes,” Euthyphro replied, but a bit sulkily, Jussi thought.

“Well, I just want to know what that thing is. But you are keeping it hidden from me,” Socrates chided.

“Okay Socrates, listen closely to me, because I don’t have much time or much more patience. What all the gods love is pious and what all the gods hate is impious. There is your form. Are you happy now?”

“Don’t be angry with me, my young friend,” Socrates said while placing a hand on Euthyphro’s arm, “I am just trying to learn what I don’t know. And I don’t really understand your definition.”

“How can you not understand me? I am perfectly clear.”

“Well, perhaps I will understand after you answer one more question: Is the pious act or pious thing loved by the gods because it is pious, or is the act pious because it is loved by the gods?”

“Sometimes I loathe you, Socrates,” Euthyphro hissed. “You are like Daedalus’s statutes; when a person looks at them they are pointing one way, then when he turns around the statutes point another way. Just when I think I understand something, you come along to try and confuse me. But I won’t allow it. I am the priest; I know what is pious!”

With that speech, Euthyphro turned and stalked off into the courthouse.

Turning back to the newcomers, Socrates broke out in laughter. “He seems a bit mad at me.”

Crito’s deep laughter rolled in waves, as Hiski chuckled and Jussi looked confused.

“Well, what did you learn, my boy?” Socrates asked after kneeling down so he was level with Jussi.

“He really doesn’t like you.”

Continuing to chuckle, Socrates replied “Yes, he is a bit mad at me right now, but he will come around. He really is just a bit hot in his temper. But what else did you learn?”

“He doesn’t know the meaning of righteousness and unrighteousness.”

“So right,” Socrates retorted, slapping Jussi’s shoulder. “And here is what I want you to remember: the smarter person is the one who knows he doesn’t know something, not the one who thinks he knows something but really doesn’t. Does that make sense?”

“Yes, it means we must know ourselves, like my grandpa always says,” Jussi replied.

With spit flying from his mouth, Socrates again burst in laughter, along with Hiski and Crito.

“He says that all the time, huh? I will have to remember that.”

Scene 5—Socrates’s Trial

“We better get going,” Socrates said. “I am late for my own trial.”

“Let’s just skip the trial and escape, Socrates,” Crito suggested. “You don’t need to go through this. You know what is more than likely to happen.”

“Do you really think I can do that, Crito? Haven’t I always complied with the laws of Athens? Haven’t I always obeyed? It is better for me to obey the laws and face death than to break the laws and flee. You won’t persuade me otherwise, so let’s go.”

Socrates led the way to Law Court C, shoving a passageway through the crowd for Crito, Hiski, and Jussi.

“Look at the way the people part to give Socrates room,” Jussi whispered to Hiski.

“Yes, he is a force, isn’t he? It’s his military bearing,” Hiski replied, keeping pace with Socrates. “It’s intimidating.”

“Socrates was a soldier?”

“Oh yes, for a very long time. He was a heavy infantryman, called a Hoplite. I heard that he fought very well and distinguished himself on the battlefield, especially in the Peloponnesian War. Other soldiers looked to him for courage and leadership. Don’t let the fact that he is a philosopher make you think he is anything less than a warrior,” Hiski finished just as they entered the Law Court.

“Socrates! I see you decided to come to your own funeral,” shouted a group of young men, slapping each other on the back in a showing of bravado.

“There was a time when the young men respected the rule of law,” Socrates replied. “But you have been softened by lack of work and a shortage of discipline.”

Black clouds crowded the young men’s faces, but they dared not approach the old soldier as Socrates took his position in the middle of the crowd.

“Why are there so many people here?” Jussi asked Crito.

“Most of them are jurors. There are 501 of them.”

“Why are there so many?”

“That is a pretty standard size for a trial like this. On many occasions there are even more.”

“Why?” Jussi asked.

“That is the way of Greece. The jury is very important. First it will hear the arguments and evidence from both sides and decide guilt or innocence. Then, if Socrates is found guilty each side will get a chance to suggest a punishment, which the jury will also decide.”

“Is Socrates really in trouble?”

“I am afraid so, my young friend. He is in a lot of trouble. But let’s listen now because Socrates’s turn is coming up.”

Being on the leading edge of the crowd, Crito, Hiski, and Jussi were well positioned to hear the arguments.

Socrates’s voice was strong, carrying throughout the entire Law Court so that everyone heard him without straining.

“Why am I here, people of Athens?” he asked. “What have I been accused of? Two things: corrupting the youth and not believing in the same gods as most of you.”

At this statement, the young men started jeering.

“Be calm, people of Athens, I implore you, and let me make my defense. That, after all, is what the laws require.”

Accepting the rebuke, the crowd quieted.

“First, let me address the notion that I am corrupting the youth. It is true that I am a bit of a gadfly and that I go around questioning people to discover if they are wise. And it is true that the young men follow me around, some to learn, but most to see their elders proven wrong. But what am I to do? For the gods have shown me that the unexamined life is not worth living. So I try to help people see their true self; I try to help people see the flaws in their beliefs; and I try to help people see the truth. If the young men follow me for bad purposes, why am I guilty of their sins?”

“But you claim you are smarter than everyone else in Athens,” an anonymous juror yelled from the back of the crowd.

“I have never made such claim. As you know, it was the oracle at Delphi that made that claim, and I have spent years trying to prove the oracle wrong. First I went to the politicians because I thought surely they are the smartest people around. But when I questioned them, I only found that they think they know things when they in fact do not. So, it is true, I concluded I was smarter than them. But not because I am knowledgeable; it is because I know that I am in fact ignorant. The same happened with the poets, who think that because they write poetry they can also expound on all other topics.”

Jussi whispered to Hiski, “That’s just like movie stars in our time!”

Hiski shushed him and turned back to continue listening.

“Lastly,” Socrates continued, “I turned to the craftsmen. Surely, I thought, these people know something very valuable. But they were just like the poets, thinking that their knowledge of how to make a product made them wise in everything else. And this assumption overshadowed their knowledge. So I went back to the oracle and asked him whether I was the better for being knowledgeable of my ignorance, or whether I should seek to learn a craft. I testify to you here today that the oracle declared that I am the better, not because I am smarter, but because I know I am not.”

“But the youth follow your meddlesome ways, Socrates, leading to the destruction of all our values,” cried one of Socrates’s accusers.

“I do not believe that helping others know themselves is corrupting anyone, even the youth. And let’s be truthful, as the laws require. I am not being prosecuted for this, but for embarrassing politicians, poets, and craftsmen who think they know everything.”

“You should have sent the youth away when they were listening to you,” another juror screamed.

“I do not control who comes and who goes in this city,” Socrates retorted.

“Your troublesome ways are bad for the city,” another screamed.

“That is for you, the jurors, to decide. But let me move on to the second accusation. Jurors, listen to me. When have you ever heard me discount the gods of Greece. Like you, I believe in the gods. This charge is not about my unbelief, but about my daemon.”

“You are guilty of believing in demonic gods!” screeched a young man with hatred in his voice.

“No, my young friend. As most of you here know, I have a voice that guides me. It tells me where to go and when to go. It protects me as it did in the war, and I always obey it. Call it what you want, a daemon, a god, an inner voice. It doesn’t matter. It is for this I am being prosecuted.”

“Are you finished with your defense, Socrates?” the head juror asked.

“Yes, I am done. That is my defense.”

“Then the jury will convene and vote on your guilt. Please come back in one hour, Socrates.”

Following those instructions, Socrates, Crito, Hiski, and Jussi left the Law Court and headed to a quiet place in the agora.

Scene 6—The Verdict and the Sentencing

Once they found a quiet spot on the steps next to the armless statue of a Greek beauty, Hiski turned to Socrates, “You do know that they are going to find you guilty, right?”

“That is the likely outcome.”

“Then let us make our escape. We have the plan drawn up, with people ready to receive you and shepherd you to Rome. And if you don’t want to go to Rome, we have people in several Greek cities who are willing to house you.”

“Hiski, stop. I am grateful to you and Crito for making these plans. I truly am. But I can’t flee. I have lived my life following the laws of Athens. If I can’t persuade the people of this great city that I am innocent under the laws, then I must accept their punishment under the law. If I can’t persuade, I must obey.”

“But we can’t accept this sin against philosophy,” Hiski pleaded.

“If I am found guilty, it is better that I obey, even if I die. Philosophy needs honesty; philosophy needs principles. I can’t disobey philosophy. So enough. It is about time. Let’s go see if I am victorious.”

Socrates led the way again, with the other three following dejectedly behind.

When they arrived, the jury was already assembled. “Socrates, we have come to our verdict. You are guilty of both charges. What do you think your punishment should be?”

Socrates paced before the jury. “My punishment? My fellow Athenians, I have dedicated my life to making you better, to helping you examine your lives with the sole intent being to improve the lives of all Athenians. For that I was found guilty. My punishment? My punishment should be free meals at the Prytaneum,” Socrates’s voice boomed.

“How dare you,” a juror screamed. “I suggest death, and even that is too good for you.”

“Death!” the jury shouted in unison.

“So death it is, Socrates,” the head juror announced. “Do you have anything else to say before you are taken to the prison?

“Yes,” Socrates replied. “Men of Athens, death is not hard for us. It is simply a passing into the next life. It is living a good life that is hard. Evil works its way against us to weaken our morals and degrade our virtues. Every day we must stand against this; every day we must work for good. So I accept your verdict and look forward to the future. But you are wrong if you think killing me will end the reproach of you. Philosophy will live and expand and grow. And your guilt against philosophy will become widely known, causing you to be reviled for eternity. Again, because I die, philosophy will grow. So I go freely to my death, for the sake of philosophy.”

With these last words, Socrates turned and walked to the jail to take his place on death row.

Scene 7—The Death of Socrates

“Maybe Jussi shouldn’t be here,” Crito said.

At the mention of his name, Jussi moved his diminutive frame further behind Hiski, and Hiski placed a hand on his head for encouragement.

“He needs to be. He needs to see and remember so he can prevent this in the future,” Socrates reminded Crito and Hiski. It will be hard, but he may be the Philosopher someday.

“The Philosopher?” Jussi wondered at the statement, wishing he were anywhere but in this cell right now.

“Grandpa, can’t we leave? I don’t want to be here anymore.”

Hiski moved his hand to Jussi’s shoulder and pulled him in tight in a protective hug. “Not yet, my boy, but I’ve got you. You are safe.”

Moving closer to Hiski, Jussi turned his attention back to the scene unfolding in front of him. Socrates had just finished talking to his wife and children, and he had sent them out with kisses and tears.

Visibly moved by the departure of his family, Socrates turned to the rest gathered in the small cell, “Well, we will have no more of that. I wish to depart without any more emotion. Plato, straighten your back, young man.” Plato backed further into the dark corner where he had been standing and wiped his eyes with the sleeve of his tunic.

Breaking the sudden silence, Crito asked Socrates, “What instructions do you have for us who remain?”

“Crito, my oldest friend. Will you care for my family?”

“It has already been arranged. They will be provided for as if they were my own.”

“Then I have only one more concern,” Socrates replied, lowering his bulky frame to the bunk. Turning to Plato, who remained in the corner fighting the rising tears, Socrates spoke in a voice Jussi had heard before. It was the voice of the Philosopher from his first adventure to Greece, from his adventure to the Cave. It rolled out of Socrates, deep and strong and smooth. “We must pass the mantle of philosophy. Plato! Come here my boy and sit beside me.”

Plato moved slowly from the dark corner where he had been struggling with his emotions and sat close to Socrates.

Socrates took the cloak he had been wearing from around his shoulders and placed it across Plato’s back. “The mantle of philosophy is now yours.”

“No!” Plato started, with a look of horror spreading across his face. “I am not worthy to replace the wisest of us all.”

A deep rolling laugh burst from Socrates as he threw his head back in laughter. “The wisest!” he sputtered. “No, my boy, not the wisest. Just the most ignorant.”

“But—”

“No more excuses, Plato. I have seen the future of philosophy from Hiski, and you are its next heir. You will take us from our infancy and bring us into the world. Your writings will change the course of science and religion and culture and literature. You are he. You are now the Philosopher.”

With that declaration, Crito leaned over in front of Plato and kissed him on the cheek. “You have my help, my boy, whatever help this old man can be.”

“And don’t forget about the future of philosophy, standing right there in front of you,” Socrates said while pointing to Hiski and Jussi. “They will guide you as they guided me.”

Hiski moved to Plato and, like Crito, kissed him on the cheek. “You only have to call this simple, old man and he will come,” Hiski whispered.

“Simple indeed,” Plato retorted. “I suspect not. But I will call.”

“And you, Jussi,” Plato said, pointing at Jussi and waving his hand for him to come over. “Will you come when I call? For I suspect that philosophy will have great need for you.”

Jussi’s voice stuck in his throat. All this talk of his role in philosophy scared and confused him. He settled for nodding his head.

Plato leaned over and kissed Jussi’s cheek. “The future will need you, so study my boy. Study.”

Jussi moved quickly away, to hide behind Hiski’s frame once again, confused even more.

“There we have it. The mantle has been passed. So now it is time. Crito, call the guard.”

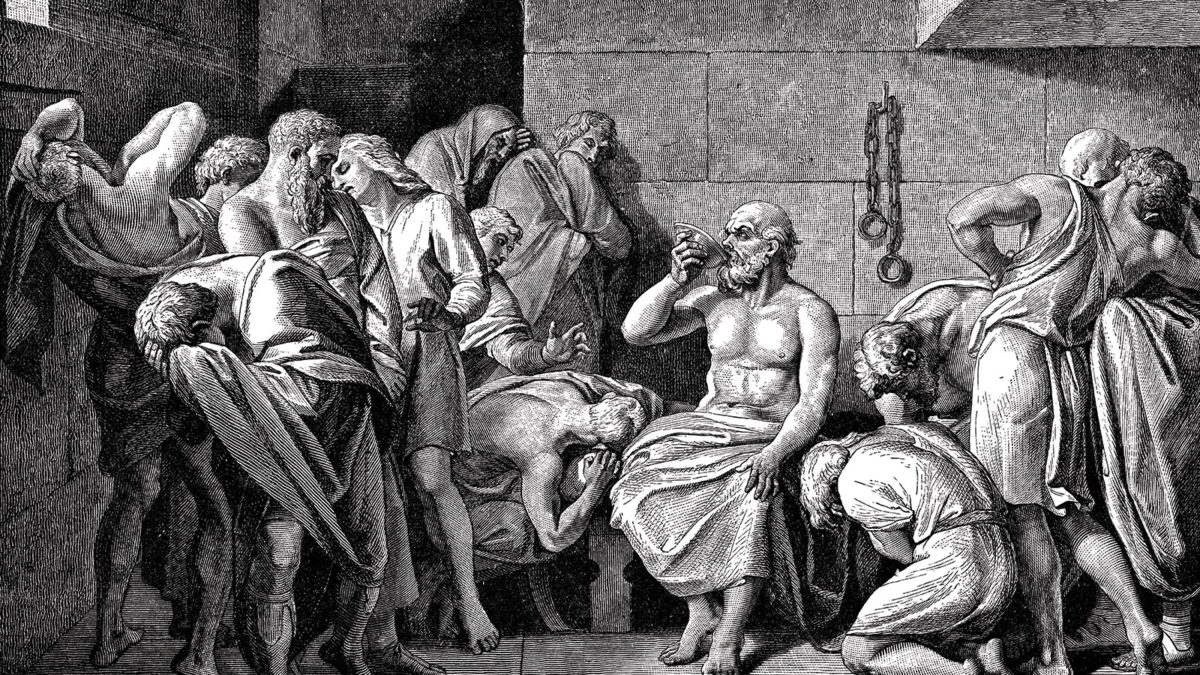

Hearing his named called from down the hallway, the guard brought the poison in a wooden chalice.

“How do I do this, my good friend?” Socrates asked, for he and the guard had talked long into the previous night, until the guard converted to philosophy.

“Drink it all straight down. It is hemlock, so it will taste bitter. It is okay to then take some water to rinse the taste from your mouth. If you walk around, it will speed the process and save you some digestive pain. When your legs begin to feel numb, lie down. The process will not take long after that. You will slowly begin to feel cold and then go numb. The end will come a few minutes after that.”

“Thank you, my friend. I will remember you to the gods when I see them.”

When the guard departed, Socrates took the cup and gave thanks to the gods for a long life, for philosophy, and for his friends. Finishing his thanks, he drank the cup in one long draught.

Those gathered around began to weep, and tears rolled freely down Jussi’s cheeks.

“Again, we will not have that. Hiski taught me a new word the other day, a word from his people in the future called the Finnish. The word is Sisu. We Greeks would call it the gritty determination to grasp the adventure within us. My friends, thank you for being here and helping me find my Sisu. I go to a new adventure.”

Socrates walked in silence for a few minutes, touching the heads of those gathered with him. When his legs began to go numb, he lay down on the cot. “Crito, one last request if you will permit me.”

“Anything, my old friend.”

“Give Hiski a small amount of gold for Maggie, for her education. She will need it, and philosophy will need her.” And with that, Socrates closed his eyes and passed into his future.

“This is Athens’ greatest sin,” Plato whispered, “a sin from which it will not recover.”

Scene 8—Home

Having changed back into their clothes and said their goodbyes to Crito, Hiski and Jussi made the return trip to the trailer.

“Grandpa?”

“Yes, my boy, I imagine you have many questions.”

“Who’s Maggie?” Jussi asked with a hint of jealousy tingeing his voice.

Hiski waited to answer while he stuffed a small amount of tobacco into his pipe and lit it. “Maggie isn’t born yet, and she won’t be for many years. But she will be very special to you. That is all I can say. Trust me, Jussi, that is all I can say.”

“Okay. Is Socrates gone forever?”

“No.” Hiski replied in his usual reserved manner.

“Where is he then?”

“His spirit lives in the next Philosopher, Plato. And his shade lives in the next life. If you are lucky, you may run into him someday.”

“How?”

“You forget your studies, my boy. Time rolls up for all of us. The present and the past become the future, and time becomes one. In that point, you can see him and talk to him. But this will make more sense soon. Let us get some sleep. It’s been a long and trying day.”

As his eyes were closing, Jussi thought only one thing, “Who is Maggie?”