How Successful is Your Mentoring Program?

Measuring a Program’s True Impact

October 2022

Download This Article (.pdf)

The success of a formal mentoring program can be difficult to measure. It largely depends on the users’ experience, and user experience varies from person to person and program to program. But indicators of success are almost always required for a mentoring program’s growth and sustainability. Stakeholders want to be able to point to tangible impacts to justify the allocation of time and financial resources needed to keep the program operational. After all, “What gets measured gets managed.”1

Unfortunately, law firms, government law offices, law schools, bar associations, and other legal organizations tend to measure their mentoring program’s success incorrectly or not at all. Most legal organizations focus on the program’s metrics, but the best indicators of a program’s success are actually the learning outcomes. Additionally, when programs establish and build on a theory of change in their program development, that theory can lead to improved evaluation and reporting processes as the program matures. This article discusses some practical ways for legal organizations to measure their mentoring program’s true impact.

Establishing a Theory of Change

A theory of change is an organization’s set of beliefs and hypotheses about how its activities lead to outcomes that contribute to a program’s overall mission and vision.2 Often developed during the planning stage of a mentoring program, a theory of change is useful for monitoring and evaluating a mentoring program as it grows and sustains over time. It can help organizations devise better evaluation tools, identify key indicators of success, prioritize areas of data collection, and provide a structure for data analysis and reporting.3

Developing a theory of change is a lot like designing a mentoring program. You’ll need to:

- identify the people you’re working with (your audience);

- determine the needs and characteristics of your audience; and

- establish the program’s final goals (what the program aims to achieve for your audience).

A program’s final goals should be realistic and succinct, forward looking and relatively long-term, and engaging for stakeholders. You should set no more than a few final goals, and it is often best to set just one.

Many legal organizations struggle to articulate appropriate and actionable final goals for their mentoring program, and so the goals wind up being too broad or impracticable. For instance, a law firm might focus on “improving outcomes” for program participants in areas such as employment prospects, practice competencies, and leadership potential. While noble in spirit, these final goals are overly broad, and the correlation of the mentoring program to the outcomes is nearly impossible to measure. Presumably after some time in the legal profession, every lawyer will have improved employment prospects, practice competencies, and leadership potential. The mentoring program’s impact on these outcomes may be tangential at best.

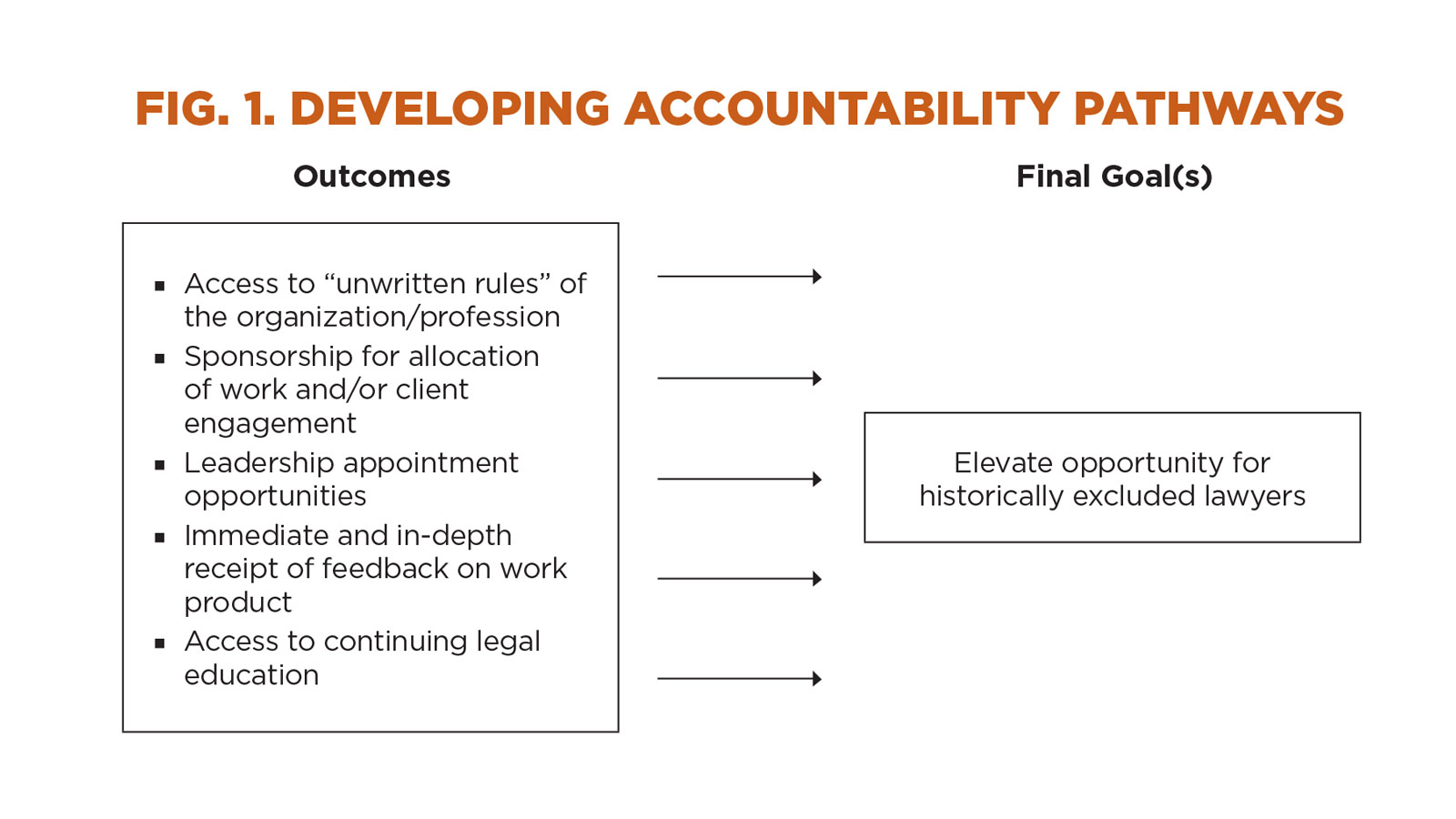

Or a bar association might focus on “elevating opportunity” for lawyers from communities that have been historically excluded within the profession. Again, while an important and admirable goal, it’s impracticable because it’s too dependent on external factors such as systemic and structural racism and other barriers in the legal profession. Organizations should consider what their mentoring program is accountable for and what’s beyond its sphere of influence.

A good way to better articulate a final goal that’s too broad or overarching is to draw accountability lines between the outcomes the program achieves and the longer-term goals to which these outcomes contribute.4 Developing accountability pathways allows the organization to work backward from the final goals to identify the intermediate outcomes needed to achieve the final goals. These intermediate outcomes are the changes the users or beneficiaries experience by engaging with the program activities. Figure 1 shows possible accountability pathways for a mentoring program whose final goal is “elevate opportunity for historically excluded lawyers.”

Establishing intermediate outcomes is perhaps the most important part of measuring program impact. Many organizations jump from their program activities to their final goals without thinking through the changes that need to happen for program participants in between engaging in program activities and reaching the final goals. Intermediate outcomes, when clearly articulated, are things your program can directly influence through its activities. Outcomes should be feasible given the scale of the activities. They should be short-term but should link logically to your final goals. And ideally, they should be supported by evidence that such outcomes help achieve your program’s final goals.

Establishing intermediate outcomes is perhaps the most important part of measuring program impact. Many organizations jump from their program activities to their final goals without thinking through the changes that need to happen for program participants in between engaging in program activities and reaching the final goals. Intermediate outcomes, when clearly articulated, are things your program can directly influence through its activities. Outcomes should be feasible given the scale of the activities. They should be short-term but should link logically to your final goals. And ideally, they should be supported by evidence that such outcomes help achieve your program’s final goals.

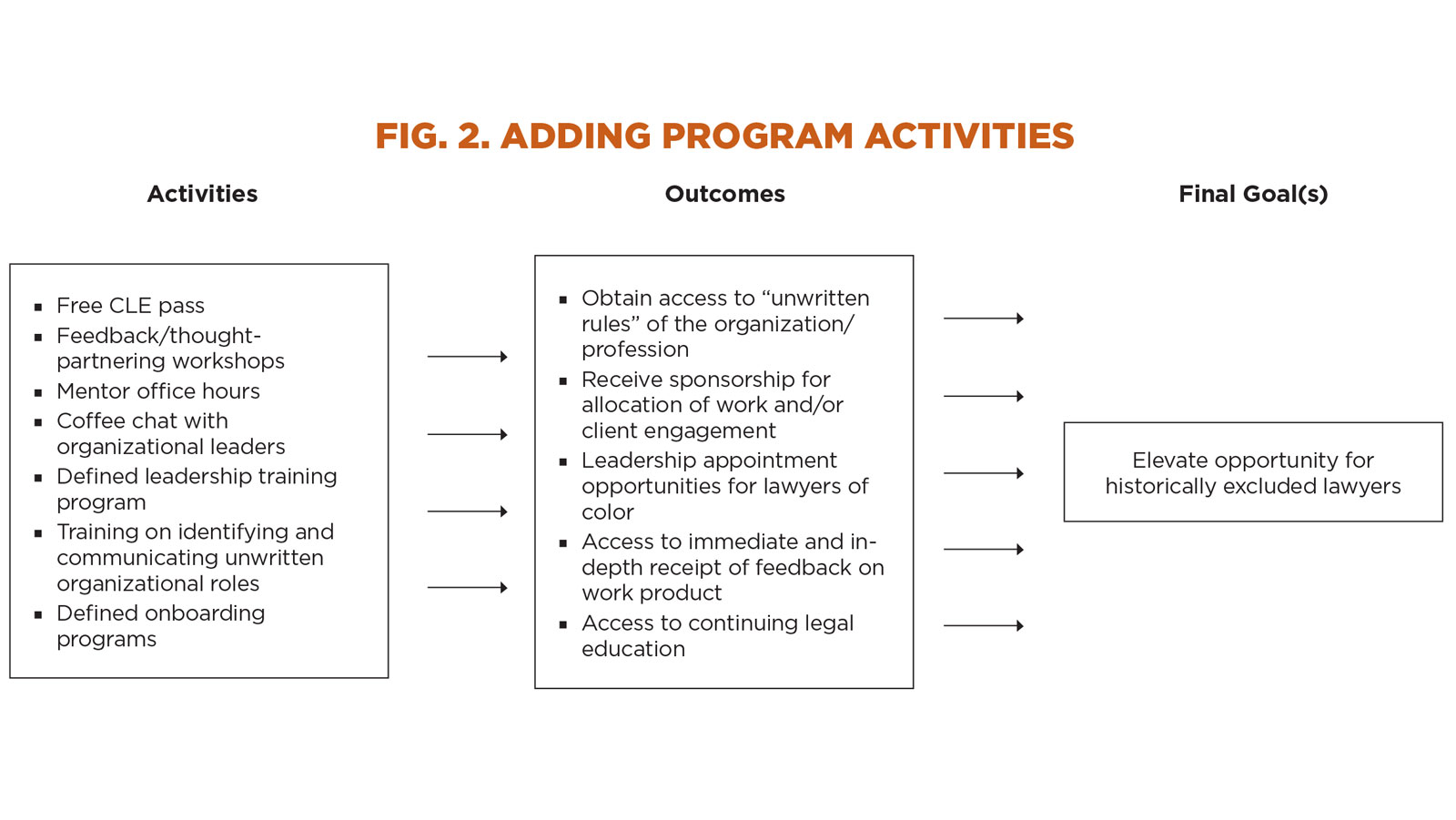

Once you’ve established your final goals and intermediate outcomes, consider how the program activities will make this change happen. Take each intermediate outcome in turn and think about how it links to your activities. Consider the features that make the activities successful and whether you’ve overlooked any intermediate outcomes. Figure 2 shows what adding program activities to the earlier accountability chart might look like.

At this stage, it’s important not to focus too heavily on how your theory of change will be measured. Ultimately, a program should not be designed around what can be measured. The mechanics of measurement can be addressed later. However, throughout the accountability process, consider what evidence already exists that’s relevant to your theory of change. Ideally, this will be in the form of references to published research, but you could also include your own organization’s experience and data. You may find some evidence that contradicts your theory. Think this through, and if necessary, modify your activities to reflect what the evidence tells you. If you don’t have evidence, then identify your assumptions about why a specific activity will lead to a specific outcome or why an intermediate outcome will lead to a final goal.

At this stage, it’s important not to focus too heavily on how your theory of change will be measured. Ultimately, a program should not be designed around what can be measured. The mechanics of measurement can be addressed later. However, throughout the accountability process, consider what evidence already exists that’s relevant to your theory of change. Ideally, this will be in the form of references to published research, but you could also include your own organization’s experience and data. You may find some evidence that contradicts your theory. Think this through, and if necessary, modify your activities to reflect what the evidence tells you. If you don’t have evidence, then identify your assumptions about why a specific activity will lead to a specific outcome or why an intermediate outcome will lead to a final goal.

Your theory of change will depend on your program’s “enablers”—conditions or factors that need to be in place for the program to work.5 Enablers can be internal or external. Internal enablers are those mostly within your control, such as your staff, administrators, and mentors. External enablers are often beyond your immediate control. They can include social, cultural, economic, and political factors; external rules, regulations, and policies; and outside organizations and stakeholders. The program enablers can substantially help or hinder your program’s activities. Within your program accountability chart, you can create an additional layer showing the relationship between your program enablers and the program activities.

Once you’re satisfied with your theory of change, you can start thinking about how to measure and evaluate it.

Outcomes versus Metrics

A metric is essentially a standard of measurement. To apply metrics to a mentoring program, where learning is the most substantive outcome, you have to come up with something to measure. You might measure the number of participants who complete the mentoring, or the quality of the program by its cost, return on investment, or efficiency. Ultimately, however, learning outcomes are the most important indicators of a program’s overall success. If you aren’t measuring your learning outcomes, you have to wonder why you are providing a mentoring program at all.

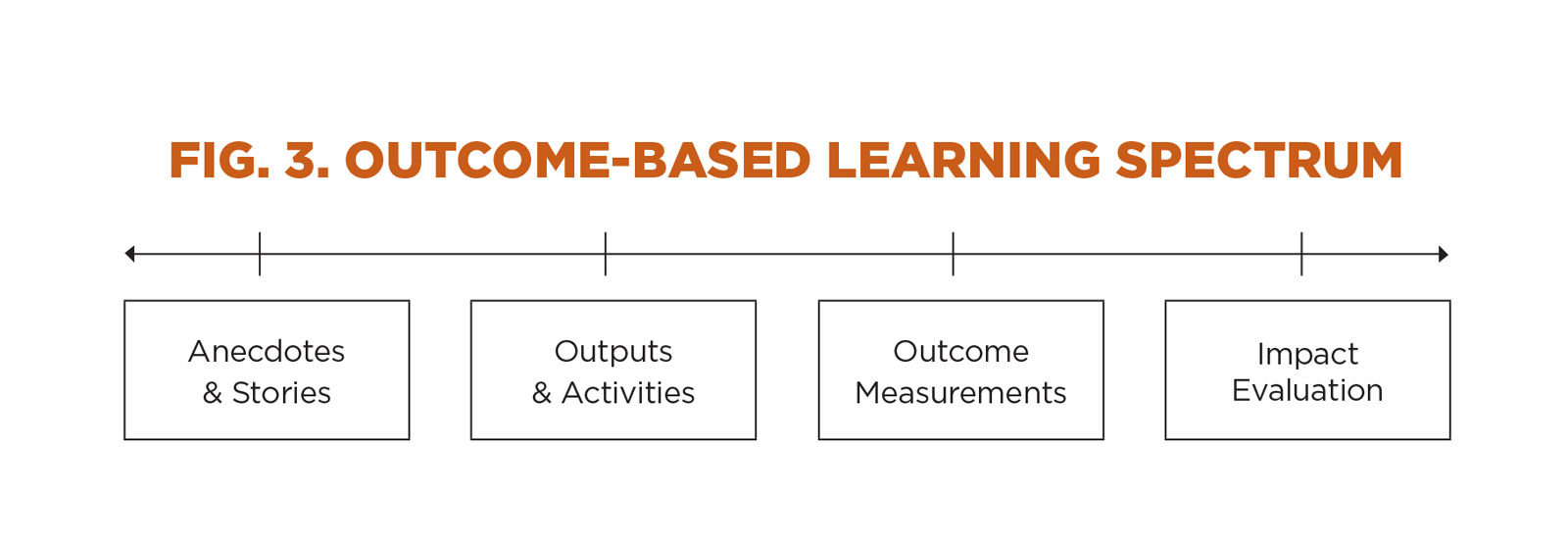

Figure 3 shows outcome-based learning when measured on a spectrum. At the low end of the spectrum are anecdotes and stories from program participants. While these can be useful, they may not indicate true outcome achievement or trends. Despite the lack of connection between anecdotes/stories and outcomes, they’re often used to engage internal stakeholders in the mission and vision of the program.

The next level on the spectrum is program output and engagement in activities. Most organizations focus their effort here, because they’re familiar with measuring and reporting the quantitative aspects of a program, such as number of participants, program cost, participant demographics, activity engagement, and program completion.

The next level on the spectrum is program output and engagement in activities. Most organizations focus their effort here, because they’re familiar with measuring and reporting the quantitative aspects of a program, such as number of participants, program cost, participant demographics, activity engagement, and program completion.

The higher levels of the spectrum are outcome measurements and impact evaluation. This is where organizations struggle, because they don’t know how to qualitatively measure outcomes and impact. Outcome-based learning looks different than traditional metric collection, so it needs to be measured differently.

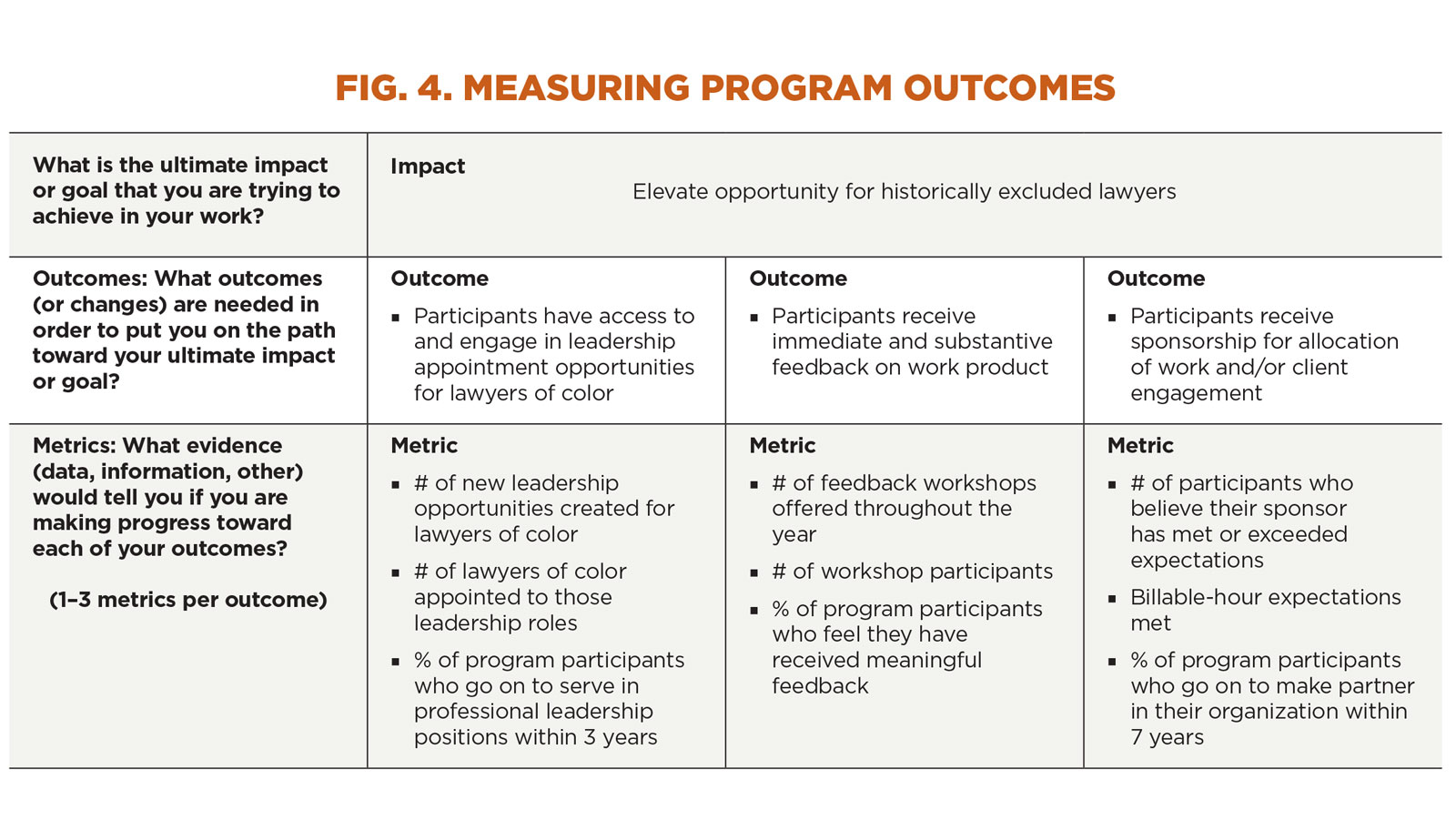

The good news is that once you’ve developed a theory of change and created an accountability chart that accurately describes the connection between your program activities, program outcomes, and final goals, you are well positioned to measure your program outcomes. The methodology discussed here involves both outcomes and metrics to convey program impact. The “impact” will be your final goal, the “outcome” will use adjectives or verbs to describe the desired change, and the “metric” will use numbers and percentages to approximate progress in reaching an outcome. Figure 4 shows what this might look like for our example organization.

You can use this model to begin developing the quantitative metrics that will provide data to support your mentoring program outcomes and ultimately support the program’s input. The key is to know what you’re measuring and directly connect the metric to the program outcome. Don’t just connect general program metrics to outcomes and hope for the best. Once you’ve determined these metrics, you can then incorporate the participants’ stories and anecdotes to elaborate on these metrics and further engage stakeholders.

You can use this model to begin developing the quantitative metrics that will provide data to support your mentoring program outcomes and ultimately support the program’s input. The key is to know what you’re measuring and directly connect the metric to the program outcome. Don’t just connect general program metrics to outcomes and hope for the best. Once you’ve determined these metrics, you can then incorporate the participants’ stories and anecdotes to elaborate on these metrics and further engage stakeholders.

The Kirkpatrick Model

So, how do you quantitatively measure a qualitative user experience in an outcome-based learning program? The Kirkpatrick Model provides a simple and effective means to evaluate user experience through quantitative methodology.6 It has four levels: reaction, learning, behavior, and results.

Level 1: Reaction

This first level measures whether learners find the training engaging, favorable, and relevant to their position or reason for program engagement. A crucial component of the Level 1 analysis is a focus on the learner versus the trainer. Thus, in mentoring programs, the focus here is on the mentee’s takeaways rather than the skill or ability of the mentor.

This level is most commonly assessed by a program closure survey that asks participants to rate their experience in the program. Assessments can also be done at various intervals throughout the program. The main objective is to ascertain whether the program met the participant’s needs. Organizations should encourage written comments and honest feedback.

Level 2: Learning

Level 2 assesses whether the learner acquired the intended knowledge, skills, attitude, and confidence from the program. Learning can be evaluated through both formal and informal methods and should be evaluated through pre-learning and post-learning assessments to identify accuracy and comprehension.

Methods of assessment include comparison surveys or interview-style evaluations. In mentoring programs, this might look like a pre-program assessment of the participant’s knowledge, relationships, and professional goals as compared to a post-program assessment of the same items. Here, it’s important to use a clear scoring process to reduce the possibility of inconsistent evaluation reports. A control group may be used for comparison.

Level 3: Behavior

Level 3 measures whether participants were truly impacted by the learning and if they’re applying what they learn. Assessing behavioral changes makes it possible to know not only whether the skills were understood, but also if it’s logistically possible to use the skills in the legal organization or the profession overall.

The Level 3 assessments can be carried out through observations and interviews. Assessments can be developed around applicable scenarios and distinct key efficiency indicators or requirements relevant to the participant’s role or professional goals. Self-assessment may be used here, but only with a precisely designed set of guidelines.

Level 4: Results

The final level measures the learning against the program’s articulated outcomes. Analyzing data at each level allows mentoring programs to evaluate the relationship between each level to better understand the training results—and, as an added benefit, allows organizations to readjust plans and correct course throughout the learning process.

Conclusion

Quantitative metrics play an important role in measuring the impact of a mentoring program, but it’s the ability to make those metrics accountable to program outcomes that conveys true program impact. To make measurements matter, organizations should focus on building a theory of change that incorporates meaningful program outcomes and measurements of those outcomes. After all, if you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it. To do right by your mentoring program participants and to effect the change you wish to see in the profession, you must do what it takes to correctly and substantively measure the learning that occurs within mentoring relationships.

Notes

1. This popular quote is often attributed to management theorist Peter F. Drucker, but the origin of this expression is unclear.

2. Center for the Theory of Change, What is Theory of Change?, https://www.theoryofchange.org/what-is-theory-of-change.

3. GrantCraft, “Mapping Change Using a Theory of Change to Guide Planning and Evaluation” (2006), https://learningforfunders.candid.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/12/theory_change.pdf.

4. Id.

5. Wilkinson et al., “Building a System-Based Theory of Change using Participatory Systems Mapping,” 27(1) J. of Evaluation 80 (2021), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1356389020980493.

6. More information about the Kirkpatrick Model can be found at https://www.kirkpatrickpartners.com/the-kirkpatrick-model.