Uncovering State Docket Access

March 2023

Download This Article (.pdf)

Docket research is the start of many legal workflows. Litigation strategy, calendaring, expert witness research, judicial research, and business development are all familiar legal tasks, but much of the related work starts with information in dockets. Dockets, also referred to as a register of actions or case summary, contain pertinent case information, such as case number, judge, parties, and events of the case. Given the importance of dockets within legal research, it’s no wonder that docket research has become an increasingly important task.

Federal docket research is generally more straightforward than state docket research. While federal dockets are electronically available via PACER,1 there’s no such unified e-filing system for dockets at the state level. Instead, it’s left to individual states, and sometimes even counties, to determine the availability of electronic access to their court records. To further complicate matters, some state court databases combine e-filing systems with their docketing databases, while others keep them separate. Moreover, some courts are still in the process of transitioning to online platforms, both for e-filing and docketing systems, so some records are not yet available online.

This article examines the current state of affairs regarding online access to state dockets. It begins with a brief overview of Colorado’s e-filing and docketing systems, and then addresses some of the challenges faced by other jurisdictions and what’s being done to overcome them. Finally, it looks at what’s new and what might lie ahead in the realm of state docket research.

Colorado’s E-filing and Docketing Systems

Technology has proven to be efficient and economical for court systems.2 Colorado was an early pioneer of online access when the Colorado Judicial Branch launched its first e-filing platform in 1999, making it one of the first states to make such a technological leap.3 An L.A. Times article about the new e-filing platform boldly asserted that lawyers would be able to push a button on their computer terminals to process court filings from their offices.4

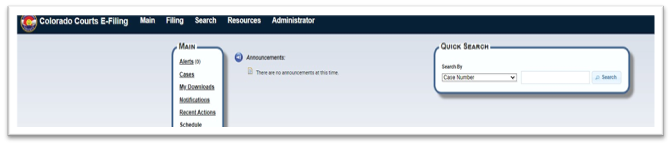

While design and maintenance of the e-filing platform was originally outsourced, the Colorado Judiciary brought the platform and public access to it in-house in 2008 by using a self-funded approach.5 Judicial approval in 2010 meant that the new e-filing platform, Integrated Colorado Courts E-filing System (ICCES), was developed and launched in 2011.6 The name ICCES was eventually changed to Colorado Courts E-filing (CCE), effective November 1, 2016, and Colorado still uses the platform.7

CCE allows eligible users (attorneys, government agencies, parties to a case, etc.) electronic access to pleadings with an e-filing account. While there’s no fee to create an account, viewing the contents of a case, including the docket, comes with an upfront cost of $15.8 Users should note that search functionality in CCE is limited, and, similar to PACER, they are paying to access documents that may or may not exist. Those who are ineligible to access CCE can purchase copies of court records using the judicial branch’s online Record/Document Request Form,9 or by contacting the appropriate clerk of the court directly.

Unlike CCE, the Colorado Docket Search tool10 on the Colorado Judicial Branch website does not require an account. The tool offers access to online case information from Colorado district and county courts, but full-text access to pleadings is not available. Users can search court records based on the county where the case was filed and then narrow the search by supplying more case information, such as the case number, a party’s first or last name, or attorney bar number.

Different State, Different Solution

Methods for accessing e-filing and state-level docketing systems are as unique as the states themselves. Differing system platforms, docket entry specifications, and levels of public access can affect a researcher’s ability to access electronic court records. State trial court access and information still varies wildly for several reasons, including funding issues and the responsibility to protect citizens’ personal information.

Funding constraints pose a problem for local courts when trying to create electronic access to court records. Local municipalities and governments are already working within a tight budget, so the high overhead cost of implementing electronic filing and docketing systems can be problematic. On top of the startup costs associated with such a major undertaking, there are additional fees for manually and electronically obtaining dockets,11 as well as ongoing costs for maintenance and personnel.

If an in-house solution is not feasible, third-party state docketing databases, such as Tyler’s Odyssey File & Serve, enable the electronic filing of documents with courts via a secure, web-based portal; these filings are then made available to be searched and downloaded by researchers. To date, Odyssey File & Serve’s Enterprise Justice Software is used by more than 24 states.12 Texas’s implementation of the re:Search platform was the largest statewide e-filing implementation in the country and was successfully rolled out within 12 months of Texas Supreme Court Order 13-9165, which required electronic filing in certain courts.13 The ever-expanding re:Search platform14 does associate a cost with purchasing pleadings in conjunction with the ease of e-filing; however, researchers can typically sign up for a free account to view the contents of state court dockets.

The documents that receive the most public exposure via electronic access are those created by the court itself—its dockets, calendars, indexes, settlements, and case dispositions.15 Court records can contain social security numbers, names, dates of birth of minor children, financial information, and even medical records. Documents containing this extremely sensitive information should give courts pause, as the country’s fastest-growing computer-related crime is identity theft.16 Such information can also be used to commit crimes such as extortion, blackmail, and assault.17 Citizens cannot typically refuse to submit a document to a court, even if it contains personally identifying information. Courts must therefore consider ways to conceal, suppress, or limit this information or risk violating the public’s trust and confidence. Many courts have taken this into consideration and require a phone call to the court clerk to obtain these highly sensitive documents.

Organizations Aiming for a Solution

Established in 1955, the Conference of State Court Administrators (COSCA) has consistently worked to improve state court systems.18 COSCA’s mission statement includes a provision about establishing a forum to aid state court administrators with the development of their justice systems.19 COSCA has been a pioneer in the court technology arena. In 1997, COSCA discussed developing a model court case management system that was based on functionality and features.20 Today, the COSCA Guidelines for state court e-filing implementation are used by several local courts,21 and several states are updating their access policies, using the Guidelines for reference.22 Guideline recommendations touch on topics including methods of limiting information, varying levels of access, public terminals, and electronic storage of archival records.23

One additional organization, The National Center for State Courts (NCSC), works to improve the administration of justice in local courts and to gather information and produce innovations to benefit all courts.24 The Court Statistics Project (CSP), a joint effort of COSCA and NCSC, aims to aggregate and publish state court caseload data that is collected from the state court administrators’ offices.25 The CSP now provides data on state court structure, authority, reporting practices, and caseload volume and trends—something once thought unimaginable—which is invaluable to law firms and docket research.26

The Future of State Electronic Court Records

Access to state dockets has become a big business both for courts and court users. According to the NCSC, e-filing is now a billion-dollar industry in the United States, and with court budgets facing constraints around the nation, there are additional opportunities for creative growth.27 Aside from e-filing, researchers are now looking for a deeper understanding of courts and analytics on the information within dockets.

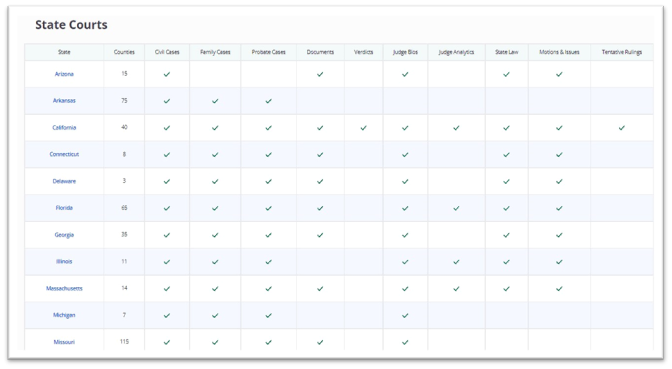

The process for accessing both federal and state dockets on larger vendor platforms, such as Lexis CourtLink, Westlaw Dockets, and Bloomberg Dockets, is straightforward for users; databases typically include access to all federal and select state courts. Smaller companies are popping up with the sole focus of providing access to local court electronic records. One vendor, DocketAlarm, has over 650 million dockets and documents and seeks to provide coverage for every litigation docket.28 Another vendor, Trellis, focuses only on state coverage, includes state judge analytics, and aims to make state trial courts and legal data more accessible and transparent.29 In fact, Trellis aims to be so transparent that it’s made its docket coverage map publicly available.

One of the features of newer docketing platforms, access to crowd-sourced documents, allows wider access to information that might have previously been more difficult to obtain, both in terms of accessibility and cost. Both DocketAlarm and Trellis use crowd-sourced documents, meaning that if someone buys a pleading on one of these platforms, other platform users who access the same docket can also access that pleading at little to no cost. RECAP is an example of crowd-sourced document access on a federal level. RECAP, which is PACER spelled backward, is software that allows researchers to automatically search for free copies of PACER documents already downloaded by other users and saved to their database.30

Courthouse News Service (CNS), which is primarily focused on civil litigation news, just revamped its service to include access to more state court documents. Historically, CNS has not provided comprehensive docket information but focused on alerting its users to new filings and rulings. While the CNS platform is not strictly focused on docket access, CNS court reporters are familiar with the access troubles surrounding local court records. In fact, CNS journalists recently traveled more than 1,000 miles to visit 25 Virginia circuit courts to demonstrate the number of resources needed to effectively cover the public record of Virginia.31 As evidenced by the results of the CNS journey, it is safe to say that accessing state court records is a costly, time-consuming practice.

Conclusion

The difficulty of conducting state docket research is knowing where to start. Whether researchers are looking for analytics or pleadings, until a state-level PACER-like system exists,32 this type of research will continue to be a challenge. As courts work to assess and improve their digital tools, they will need to combine technology with other process improvements and implement the guidelines that others already have identified as essential. Additionally, courts must incorporate feedback from their users and, despite a lack of a universal solution, users must continue to endeavor in their state court research.

Related Topics

Notes

1. US Courts, “25 Years Later, PACER, Electronic Filing Continue to Change Courts” (Dec. 9, 2013), https://www.uscourts.gov/news/2013/12/09/25-years-later-pacer-electronic-filing-continue-change-courts.

2. Sudbeck, “Placing Court Records Online: Balancing the Public and Private Interests,” 27-3 Just. Sys. J. 268 (Fall 2006).

3. Cornelius and Medina, “Integrated Colorado Courts E-Filing System: The Next Generation of E-Filing,” 41 Colo. Law. 87 (2012).

4. Associated Press, “Colorado May Allow Lawsuits on the Net,” L.A. Times (Aug. 6, 1999), https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1999-aug-06-fi-63103-story.html.

5. Cornelius and Medina, supra note 3.

6. Id.

7. Colo. R. Crim. P. 49.5.

8. There’s a growing momentum to eliminate paywalls and make court documents available to the public for free. The “free versus fee” discussion has been ongoing regarding filings on the federal level. See, e.g., Courtney, “PACER vs. RECAP: Fee vs. free?,” LegalNews.com (Sept. 10, 2010), https://www.legalnews.com/detroit/697813.

9. https://www.courts.state.co.us/Self_Help/Research/index.cfm.

10. https://www.courts.state.co.us/dockets.

11. Sudbeck, supra note 2.

12. https://www.tylertech.com/products/enterprise-justice.

13. Id.

14. https://www.tylertech.com/products/enterprise-justice/saas-for-courts-justice.

15. Sudbeck, “Placing Court Records Online: Balancing Judicial Accountability with Public Trust and Confidence: An Analysis of State Court Electronic Access Policies and a Proposal for South Dakota Court Records,” 51 S.D. L. Rev. 81 (2006).

16. Id.

17. Id.

18. Fetter, “A History of the Conference of State Court Administrators: 1955–2005,” COSCA (Nov. 2005), https://cosca.ncsc.org/__data/assets/pdf_file/0022/23368/history-of-cosca.pdf.

19. https://cosca.ncsc.org/mission-statement.

20. NCSC, “Developing CCJ/COSCA Guidelines for Public Access to Court Records: A National Project to Assist State Courts” (Oct. 18, 2002), https://ncsc.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/accessfair/id/210.

21. COSCA, “Position Paper on The Emergence of E-Everything” (Dec. 2005), https://cosca.ncsc.org/__data/assets/pdf_file/0025/26692/e-everythingpositionpaperapproveddec05.pdf.

22. NCSC, supra note 20.

23. COSCA, supra note 21.

24. https://www.ncsc.org/about-us.

25. https://www.courtstatistics.org.

26. https://cosca.ncsc.org.

27. COSCA, supra note 21.

28. https://www.docketalarm.com/about.

29. https://trellis.law/about.

30. “RECAP Documents No More Searchable Via Internet Archive,” RECAP The Law, (Apr. 19, 2010), https://web.archive.org/web/20160601170043/https://www.recapthelaw.org/2010/04/19/recap-documents-now-more-searchable-via-internet-archive/#menu.

31. “Report: Access to public records in Virginia courts,” Courthouse News Service (Oct. 12, 2022), https://www.courthousenews.com/report-access-to-public-records-in-virginia-courts.

32. Hudgins, “Why We Won’t See a Nationwide State Court Docket System Anytime Soon,” LegalTech News (July 16, 2020).