Can Robot Lawyers Close the Access to Justice Gap?

Generative AI, the Unauthorized Practice of Law, and Self-Represented Litigants

December 2024

Download This Article (.pdf)

Generative AI could help litigants who are unable to afford legal services. But the greater availability of AI carries risks, including the risk that generative AI resources intended for nonlawyers will provide inaccurate legal information or engage in the unauthorized practice of law. This article discusses that tension.

Discussions of machines engaging in the practice of law were the stuff of science fiction until just a few years ago. But the revolution in AI—most notably in generative AI—is forcing lawyers and judges to consider whether AI-powered websites and apps are capable of engaging in the practice of law.

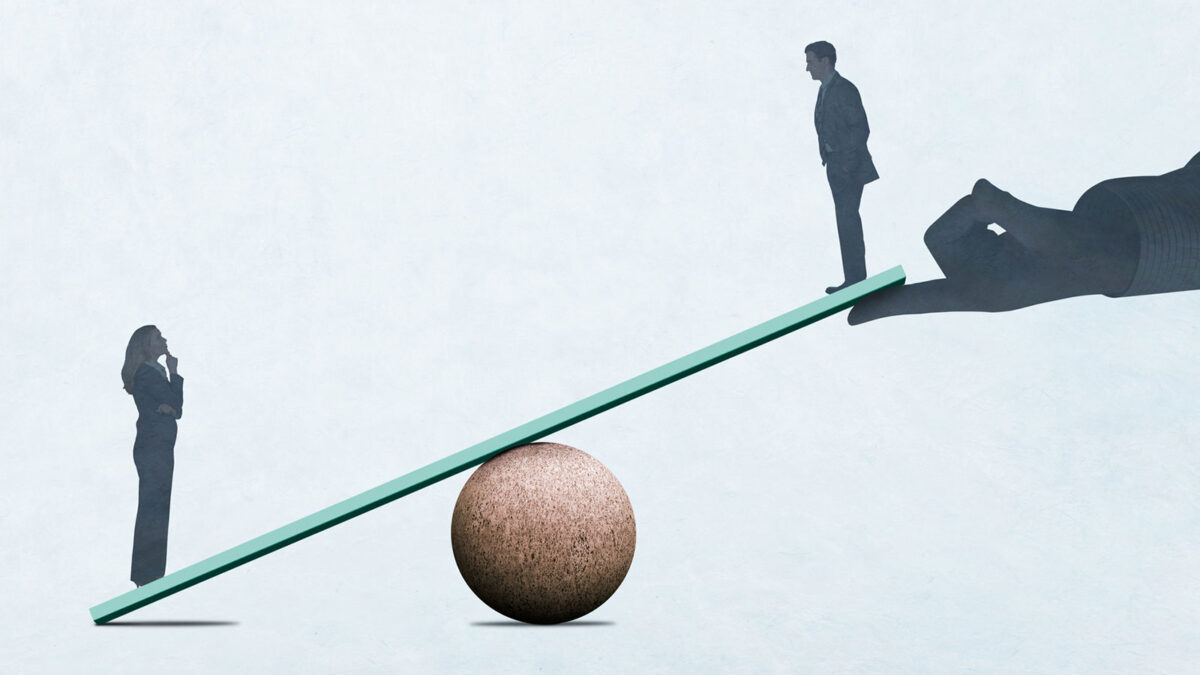

This is a conversation worth having because free and low-cost generative AI tools have the potential to help close the access to justice gap by helping individuals with limited resources gain access to the legal system. Too many people cannot afford a lawyer to assist with everyday problems such as a threatened eviction, a divorce, or a persistent creditor.

AI tools hold the potential to revolutionize access to justice by providing anyone with internet access a means to obtain legal information, better understand their legal options, and resolve their disputes quickly and economically.1 AI-powered resources, such as chatbots and document-assembly tools, can help self-represented litigants navigate their way through the court system or find a free or low-cost lawyer.

But machines cannot become members of the bar. And the same tools that hold so much promise in opening the courthouse doors to low-income individuals could cross the line into the unauthorized practice of law.

This article explores the interplay between Colorado’s Unauthorized Practice of Law (UPL) Rules and efforts to develop AI tools to assist low-income individuals with legal problems.

The Unauthorized Practice of Law

Colorado, like other jurisdictions in the United States, bars nonlawyers from engaging in the unauthorized practice of law. Colorado criminalized the unauthorized practice of law in 1905.2

Under the Colorado Constitution, the Colorado Supreme Court has the “exclusive authority . . . to regulate and control the practice of law in Colorado.”3 The Court has explained that “[t]he purpose of the bar and our admission requirements is to protect the public from unqualified individuals who charge fees for providing incompetent legal advice.”4 The Court’s authority to accomplish this goal “includes the power to prohibit the unauthorized practice of law and to promulgate rules in furtherance of that end.”5 The Court has further emphasized that it “impose[s] high standards on members of the legal profession to insure faithful observance of the high moral standards embodied in our Code of Professional Responsibility.”6

To provide guidance regarding the boundaries of the unauthorized practice of law, the Court promulgated the UPL Rules, which define conduct constituting the practice of law and prohibit the unauthorized practice of law.7 The purpose of the UPL Rules is to protect the public and the integrity of the legal system from unqualified individuals who provide incompetent legal services.8

The preamble to the UPL Rules specifies four reasons for prohibiting the unauthorized practice of law:

(1) protecting the public by ensuring that people who assist others with legal matters have sufficient competence to avoid harming the liberty interests and property rights of those they assist;

(2) safeguarding the justice system and conserving limited judicial resources by ensuring that only qualified people assist others before tribunals;

(3) educating the public about what constitutes the unauthorized practice of law; and

(4) providing the public with access to the justice system at a reasonable cost by permitting nonlawyers to provide limited-scope legal representation in certain circumstances.9

The UPL Rules provide a non-exhaustive list of actions that constitute the “practice of law”:

(1) protecting, defending, or enforcing the legal rights or duties of another person;

(2) representing another person before any tribunal or, on behalf of another person, drafting pleadings or other papers for any proceeding before any tribunal;

(3) counseling, advising, or assisting another person in connection with that person’s legal rights or duties;

(4) exercising legal judgment in preparing legal documents for another person; and

(5) any other activity the Supreme Court determines to constitute the practice of law.10

But determining what acts constitute the practice of law is not always easy.11 While recognizing the difficulty of formulating and applying an all-inclusive definition of the practice of law, the Supreme Court has stated that “generally one who acts in a representative capacity in protecting, enforcing, or defending the legal rights and duties of another and in counselling, advising[,] and assisting [them] in connection with these rights and duties is engaged in the practice of law.”12

In Colorado, persons who engage in the unauthorized practice of law are subject to injunction proceedings13 and punitive sanctions.14

The Access to Justice Gap

The lack of low and no-cost options available to help self-represented litigants resolve their legal problems is one of the greatest challenges facing litigants, the bar, and courts across the country. A 2021 survey indicated that nationally, low-income households receive little or no legal help in resolving about 92% of civil legal problems that substantially impact their lives.15 Notably, nearly 75% of these households experienced at least one legal problem in the past year.16 Household income also impacts the likelihood of resolving a legal problem if one arises. Americans with a household income of $25,000 or less see complete resolution of their legal problems at a rate of only 44%.17

Recent statistics in Colorado are equally grim: last year, roughly 98% of defendants in county court civil cases, nearly 40% of district court civil litigants in cases outside family law, and about 75% of parties in domestic relations cases did not have lawyers.18 For almost all pro se litigants, this is not a matter of choice. Rather, most people who represent themselves in the Colorado courts can neither afford a lawyer nor obtain representation from Colorado Legal Services or a pro bono lawyer.19

The Revolution Has Begun

Until recently, the powerful AI tools in widespread use today were the stuff of science fiction. Now, a generative AI tool can answer questions in seconds on seemingly any topic, draft text in prose or poetry, mimic the style of famed authors, generate images and videos, and even engage in conversation.20

Generative AI resources such as ChatGPT-4, a state-of-the-art generative AI tool, are trained using large language models (LLM) to recognize and generate text.21 LLMs use massive data sets that, through a form of machine learning known as deep learning, teach the program how characters, words, and sentences function together.22

When training a deep learning model algorithm using huge volumes of data, the algorithm performs and evaluates millions of exercises to predict the next element in a sequence.23 The training creates a neural network of parameters that can generate content, such as words, images, and a command in a line of code, autonomously in response to prompts.24 As one judge explained using less technical language, “drawing on its seemingly bottomless reservoir of linguistic data,” an LLM that underlies a user interface like ChatGPT “learns what words are most likely to appear where, and which ones are most likely to precede or follow others—and by doing so, it can make probabilistic, predictive judgments about ordinary meaning and usage.”25

The key to creating effective LLM technology is in selecting appropriate materials for the data set, because a training set that includes materials containing toxic language can generate toxic outputs.26 Thus, a generative AI tool taught using a data set comprised of social media postings will produce very different results from one taught with the contents of law libraries. As one commentator noted, “Legal scholars use the phrase ‘bias in, bias out’ to illustrate the problem that occurs when you train an algorithm on a biased dataset: it will produce biased outputs.”27 The data sets underlying a generative AI tool, however, are not necessarily transparent to the user; some AI developers consider their data sets proprietary.28 Accordingly, the user of generative AI must be wary of biases and inaccuracies attributable to the materials with which the tool was trained.29

Biases in data sets can reflect those that exist in society, leading to serious unintended consequences. For example, some law enforcement agencies have used AI-powered systems to make predictions regarding the incidence of criminal activity and, thereby, to generate leads and decide where officers should be deployed.30 But police departments’ overreliance on AI can result in policies premised on bias, such as racial profiling, rather than on historical facts.31 Similarly, if the data used to train a recidivism prediction algorithm are biased because they reflect a system where Black men are disproportionately likely to be arrested, charged with, and convicted of crimes, then any outputs of the algorithm will be similarly biased and will—inaccurately—predict that Black men are more likely to reoffend.32

Companies’ efforts to use AI to help with hiring have similarly revealed the biases that can exist in training data. Between 2014 and 2017, Amazon attempted to build a tool that would rate top job candidates.33 Its programmers eventually realized, however, that the tool disproportionately preferred male applicants. It even penalized applications that referenced “women.”34 This, they learned, was because the algorithm was trained with Amazon applicant data from the prior decade, when the applicants were disproportionately male.35

Further, generative AI tools intended for the general public are not currently trained with data sets containing comprehensive, accurate legal resources. They are not consistently reliable legal research tools because they do not always provide the correct answers to legal queries and may even make up case names and citations when they do not know the answer to a question.36

Robots to the Rescue

These shortcomings aside, for people who cannot afford an attorney and who struggle to navigate our complicated system of justice, these are promising times. AI bots, with their human language-like fluency, are already enabling greater access to legal information and even legal advice. Generative AI tools like Google’s Gemini, Microsoft’s Copilot, Anthropic’s Claude, and OpenAI’s ChatGPT-4 are genuine game changers for millions of people. With AI’s astonishing speed and user-friendly interfaces that move far beyond traditional internet search tools, nonlawyers can now prompt a “conversation” with a chatbot to ask any number of legal questions—from how to file a small claims case in Denver or Grand Junction or Lamar to how to defend an eviction action.

Someone who cannot afford to hire an attorney can readily file for dissolution of marriage, prepare for mediation, or draft a separation agreement with the help of AI. For instance, ChatGPT-4 can tell a litigant which of Colorado’s 100-plus family law self-help forms to complete to file for dissolution of marriage, and it even can describe how to fill out the forms.37 Other generative AI applications can explain what mediation is and what it typically entails. Additionally, they can suggest what types of documents and information a litigant may want to take to a mediation. An earlier version of ChatGPT also reportedly generated separation agreements when prompted to do so.38

AI entrepreneurs, sensing market demand, have been busy developing applications to help lawyers and nonlawyers alike. Some of these apps may—perhaps—even replace lawyers.39 The prospect of “AI giving legal advice [is] very real.”40 For example, the Colorado Legal Services website links to “Divorce Pro,” an AI-powered online tool that Professor Lois Lupica and her team at the University of Denver Sturm College of Law developed for self-represented parties in uncontested dissolution of marriage cases.41

In addition, an engineer and a librarian founded Courtroom5, a company that offers an AI tool to assist pro se litigants with their legal matters. According to the company’s website, the tool “uses simple AI to assess patterns in past cases and recommend next steps in a user’s own case, including filing documents, making a counterclaim or challenging the case entirely.”42 The company reports that self-represented parties have used Courtroom5 “in cases of home foreclosure, medical debt and difficult divorce.”43 Courtroom5 has also sought to expand its services, reporting that it was working on “a generative AI chatbot based on anonymous case records held in its own database.”44 Courtroom5 claims to be available in all 50 states. Notably, and despite the AI tools it offers to assist litigants, the company’s website contains this disclaimer: “Courtroom5 is not a law firm, does not provide legal advice or legal services, and is no substitute for a lawyer.”

Self-Represented Litigants’ Use of AI and UPL Concerns

Not surprisingly, this increased access to legal information and legal advice through technological tools presents the risk that the tool—or its creators—will engage in the unauthorized practice of law.45 One AI application, for instance, once marketed itself as the home of the world’s first robot lawyer, an intriguing idea to be sure.46 But what exactly does that mean? Robots are not lawyers, and they are definitely not licensed to practice law (at least not yet), and AI is not infallible—even when used by lawyers.

For this reason, the legal profession needs to draw a distinction between AI tools that are designed to assist individuals with legal matters and general AI tools that are not trained to provide responses regarding the law. The latter can lead both unwitting lawyers and nonlawyers astray. While general AI tools may not raise UPL concerns, if not used properly, they could harm individuals’ ability to represent themselves effectively.47

How many nonlawyers looking for legal help will understand AI’s limits? How many will grasp that, when asked a legal question, generative AI is likely to respond quite confidently, even if the answer contains errors, hallucinations, falsehoods, or biases?48 The lawyers for the plaintiff in Mata v. Avianca Inc. were the first to be sanctioned for filing a brief drafted by generative AI that contained “hallucinated” case citations and quotations.49

They, unfortunately, were not the last. Many similar cases involving the use of generative AI to draft pleadings without the type of cite checking, editing, and proofreading needed have arisen since then,50 including here in Colorado.51

It is unclear how, or even if, nonlawyers relying on generative AI for legal assistance will be able to tell good advice from bad. This, in turn, risks placing a burden on already overburdened courts, as they work to tease out what is real case law and what is a hallucination in court filings. Indeed, courts may well see an uptick in AI-generated pleadings that appear persuasive but that are slightly or even deeply flawed.52

Other challenges involve the unwitting loss of privacy and the unintended potential waiver of confidentiality. For example, a nonlawyer may not realize that any personal or confidential information disclosed to a generative AI tool could be used for the application’s data training (based, presumably, on the application’s licensing agreement, which frequently explicitly provides for just this). Once disclosed, does this information lose its protections from production to a legal adversary?53 What recourse does a nonlawyer have for assessing legal questions based on specific, confidential information if the available platform is not confidential?

Thus, generative AI presents new risks that nonlawyers seeking legal help will be exposed to incompetent information or even fraud. But overreacting to the challenges of AI by imposing an overly narrow reading of the UPL Rules could stifle the development of AI tools that would benefit litigants who cannot afford a lawyer.

While no published Colorado case addresses the intersection between the UPL rules and the use of generative AI, recent examples from other jurisdictions show how AI developers got into scrapes with state UPL regulators.

In Florida Bar v. TIKD Services LLC, for instance, the Florida Supreme Court concluded that the respondents—who operated a website and mobile application through which drivers could receive legal assistance in resolving traffic tickets—were in the business of selling legal services to the public and thus were engaged in the unauthorized practice of law.54 The Court accordingly enjoined the company from doing business.55

Similarly, in California, an AI startup called DoNotPay, the company that once touted its product as the first robot lawyer, was prepared to have an AI-powered bot argue on behalf of a defendant in a traffic case in February 2023.56 The company planned to have the defendant wear smart glasses to record the court proceedings and to dictate responses to the court’s questions into the defendant’s ear from a small speaker.57 The system relied on text generators, including ChatGPT and DaVinci.58 According to DoNotPay’s CEO, however, as word got out about the product, multiple bar organizations threatened the company under their respective states’ UPL rules.59 After letters from regulators poured in, some including threats of criminal prosecution, the company decided to move on to less risky business opportunities.60

At least one company, Augrented, which initially used ChatGPT-3 to assist renters with legal matters such as “eviction prevention,” purported to steer away from “the UPL quagmire by making it clear that the app does not replace the need for an attorney in some situations.”61 Augrented later changed business models and now provides renters with information about landlords in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.62

In contrast, other states welcome innovators who offer technology targeted to consumers of legal services. For example, the Utah Supreme Court created the Office of Legal Services Innovation, which regulates nontraditional legal businesses and legal services, and operates a “sandbox”—a mechanism used to foster and monitor innovative methods of delivering high-quality, affordable legal services to those underserved by the current legal markets.63 The Court even indicated that it may allow alternative legal providers, including nonlawyers, to practice law in the “sandbox,” under the watchful eye of the Office of Legal Services Innovation.64

In July 2023, due to the absence of clear guidance in Colorado regarding the dividing line between technological tools intended to assist self-represented litigants and conduct that constitutes the unauthorized practice of law, the Colorado Supreme Court asked the Advisory Committee on the Practice of Law to evaluate the UPL Rules and consider whether to recommend AI-related amendments to those rules.65 Six months later, by letter dated January 18, 2024, the Access to Justice Commission requested that the Court review the UPL Rules “to determine if revisions should be made to accommodate technological advances that will impact the practice of law and access to justice.”

The Commission expressed concern that the UPL Rules “may block the adoption of new technologies in Colorado for use in the legal system.” In particular, the Commission pointed to the language of UPL Rule 232.2(c)(9) stating that “[t]he unauthorized practice of law by a nonlawyer includes . . . [o]wning or controlling a website, application, software, bot, or other technology that interactively offers or provides services involving the exercise of legal judgment.” The Commission said that other UPL Rules “may also create impediments to the adoption of new technologies for use in the legal system.” The Colorado Supreme Court then formed a subcommittee of the Advisory Committee on the Practice of Law to consider possible AI‑related amendments to the UPL Rules. Its work continues as of this writing.

Conclusion

AI, and in particular generative AI, offers the promise of expanding public access to the legal system to those who cannot afford a lawyer. While doing so creates the risk that a technological tool will cross the line into the unauthorized practice of law, the Colorado Supreme Court’s establishment of an AI subcommittee of the Advisory Committee on the Practice of Law is an important first step in evaluating how the Court may best provide meaningful guidance to innovators who seek to close the access to justice gap through technology. That work and the ever-expanding availability of generative AI resources for nonlawyers will require diligence and education to balance access to justice against the risks that AI presents, including the risk that an AI tool will engage in the unauthorized practice of law.

Related Topics

Notes

1. According to a 2023 Pew Research Center survey, most Americans—97%—own some kind of cell phone. Of those, 90% said they owned a smartphone. Pew Research Center, Mobile Fact Sheet (Jan. 31, 2024), https://perma.cc/8TZW-4ZPD.

2. See Rigertas, “The Birth of the Movement to Prohibit the Unauthorized Practice of Law,” 37 Quinnipiac L. Rev. 97, 135 n.262 (2018), https://perma.cc/U9VW-W6YN.

3. Unauthorized Prac. of L. Comm. of Sup. Ct. v. Prog, 761 P.2d 1111, 1115 (Colo. 1988).

4. Unauthorized Prac. of L. Comm. of Sup. Ct. v. Grimes, 654 P.2d 822, 826 (Colo. 1982).

5. Prog, 761 P.2d at 1115.

6. Grimes, 654 P.2d at 826. Colorado’s Rules of Professional Conduct superseded and replaced the state’s Code of Professional Responsibility, effective January 1, 1993. See Colo. Sup. Ct. Grievance Comm. v. Dist. Ct., 850 P.2d 150, 151 n.1 (Colo. 1993). Nothing about this change undermines the Supreme Court’s authority under the Colorado Constitution to regulate and control the practice of law.

7. See CRCP 232; CRS § 13‑93‑108 (stating that the practice of law without a license constitutes contempt of the Supreme Court).

8. Prog, 761 P.2d at 1115.

9. CRCP 232.

10. CRCP 232.2(b)(1)–(5).

11. See Conway-Bogue Realty Inv. Co. v. Denver Bar Ass’n, 312 P.2d 998, 1002 (Colo. 1957) (observing that questions regarding what constitutes the unlawful practice of law are “numerous, important[,] and difficult” to resolve).

12. Denver Bar Ass’n v. Pub. Utils. Comm’n, 391 P.2d 467, 471 (Colo. 1964). See CRCP 232.2(b)(1)–(5). Accord Grimes, 654 P.2d at 824 n.1.

13. CRCP 232.14. See Unauthorized Prac. of Law Comm. of Sup. Ct. v. Bodhaine, 738 P.2d 376, 377 (Colo. 1987).

14. CRCP 232.24(c)(1); CRS § 13‑93‑108.

15. Legal Services Corporation, The Justice Gap: The Unmet Civil Legal Needs of Low-Income Americans 8, 48 (Apr. 2022), https://lsc-live.app.box.com/s/xl2v2uraiotbbzrhuwtjlgi0emp3myz1.

16. Id. at 8, 18.

17. Hague Institute for Innovation of Law and Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System, Justice Needs and Satisfaction in the United States of America 50 (2021), https://perma.cc/3YCC-3WWY.

18. Colorado Access to Justice Commission, 2022 Access to Justice Commission Pro Bono Report 5, https://perma.cc/8RSB-FG7M.

19. Id. at 4–5. Because of limited resources, “[f]or every client served by [Colorado Legal Services], at least one income-eligible person is turned away. Even those who are served often receive only limited assistance when more extended representation is indicated.” Legal Aid Foundation of Colorado, How Legal Aid Helps, https://www.legalaidfoundation.org/making-a-difference/services-provided.

20. Lawyers’ use of AI tools and, in particular, generative AI tools, implicates numerous Rules of Professional Conduct. See Berkenkotter and Lipinsky de Orlov, “Artificial Intelligence and Professional Conduct,” 53 Colo. Law. 20, 21–26 (Jan./Feb. 2024), https://cl.cobar.org/features/artificial-intelligence-and-professional-conduct. On July 29, 2024, the American Bar Association released a formal ethics opinion on lawyers’ use of generative AI technology. See ABA Standing Comm. on Ethics and Prof’l Resp., Formal Op. 512, Generative Artificial Intelligence Tools (July 29, 2024). A comprehensive analysis of the ethical issues raised through lawyer use and misuse of AI resources is beyond the scope of this article.

21. “What Are LLMs?,” IBM, https://www.ibm.com/topics/large-language-models.

22. Wang et al., “Exploring New Frontiers of Deep Learning in Legal Practice: A Case Study of Large Language Models,” 1 Int’l J. Comput. Sci. & Info. Tech. 131, 131 (Warwick Evans Publishing Dec. 12, 2023), https://wepub.org/index.php/IJCSIT/article/view/607.

23. IBM, What Is Generative AI?, https://www.ibm.com/topics/generative-ai.

24. Id.

25. Snell v. United Specialty Ins. Co., 102 F.4th 1208, 1226 n.7 (11th Cir. 2024) (Newsom, J., concurring).

26. Cyphert, “A Human Being Wrote This Law Review Article: GPT-3 and the Practice of Law,” 55 U.C. Davis. L. Rev. 401, 404 (Nov. 2021).

27. Id. at 413.

28. Arkenberg et al., “Taking Control: Generative AI Trains on Private, Enterprise Data,” Deloitte: Tech, Media & Telecom (Nov. 29, 2023), https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/technology/technology-media-and-telecom-predictions/2024/tmt-predictions-enterprise-ai-adoption-on-the-rise.html.

29. See Berkenkotter and Lipinsky de Orlov, supra note 20 at 24. See also Moriarty, “The Legal Ethics of Generative AI—Part 3: A robot may not injure a lawyer or, through inaction, allow a lawyer to come to harm.,” 52 Colo. Law. 30, 38–39 (Oct. 2023), https://cl.cobar.org/features/the-legal-ethics-of-generative-ai-part-3.

30. Garrett and Rudin, “The Right to a Glass Box: Rethinking the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Criminal Justice,” 109 Cornell L. Rev. 561, 583 (Mar. 2024), https://www.cornelllawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Garrett-Rudin-final.pdf.

31. See id. Studies of predictive policing have shown mixed results, both regarding effectiveness in deploying officers and in the existence of racial disparities. Id. Los Angeles stopped using a predictive policing algorithm after concluding it was not worth the expense given the value of the information obtained. Id. at 584.

32. Cyphert, supra note 26 at 430.

33. Gershgorn, “Amazon’s ‘Holy Grail’ Recruiting Tool Was Actually Just Biased Against Women,” Quartz (Oct. 10, 2018), https://qz.com/1419228/amazons-ai-powered-recruiting-tool-was-biased-against-women.

34. Id.

35. Id.

36. See Weiser, “Here’s What Happens When Your Lawyer Uses ChatGPT: A lawyer representing a man who sued an airline relied on artificial intelligence to help prepare a court filing. It did not go well.,” N.Y. Times (May 27, 2023), https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/27/nyregion/avianca-airline-lawsuit-chatgpt.html. See generally Mata v. Avianca, Inc., 678 F.Supp.3d 443 (S.D.N.Y. 2023).

37. But when the JDF forms are updated—as they recently were—ChatGPT-4 still directs users to fill out the old forms (i.e., the forms upon which it was presumably trained). Filing these older forms with the court could create unnecessary work for judges, court staff, and litigants, as well as potentially create problems for the litigant’s case. Access to justice is undermined if a litigant is required to refile using an updated version of the form and possibly pay another filing fee—all because the individual relied on AI’s recommendation of a superseded form.

38. Notably, however, ChatGPT has also apparently declined to do so, responding that, “as an AI language model, I cannot create legal documents or provide legal advice.” Granat, “ChatGPT, Access to Justice, and UPL,” Law Product Makers Blog (Mar. 26, 2023), https://perma.cc/N8PT-4H46.

39. Lohr, “A.I. is Coming for Lawyers, Again,” N.Y. Times (Apr. 10, 2023), https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/10/technology/ai-is-coming-for-lawyers-again.html (discussing warnings that ChatGPT-style software could take over certain areas within the practice of law).

40. Kahana, “GPT-3 and the Unauthorized Practice of Law,” Stanford Law School Blog (Apr. 13, 2021), https://perma.cc/F3UW-3VGY. See also Telang, “The Promise and Peril of AI Legal Services to Equalize Justice,” Harvard Law School, JOLT Digest (Mar. 14, 2023), https://perma.cc/X3V8-QG3S (discussing how displacing lawyers may actually widen the access to justice gap as it may convince authorities that the availability of legal AI may suggest impoverished individuals no longer need human civil lawyers). Paradoxically, some of the AI tools developed with the goal of expanding access to justice carry a risk of narrowing it. Experts cite three specific examples of how AI could pose barriers to justice: (1) the cost of obtaining and implementing high-quality AI may be so high that only high-income individuals or wealthy law firms can access it, presenting an asymmetry in power between firms and individuals; (2) low-income individuals may lack the communication tools to access AI in the first place; and (3) the progression of AI may disincentivize lawmakers from enacting legislation concerning the right to counsel in civil cases. See Telang, supra.

41. See “You Agree on Everything, No Children, Want to Divorce in CO,” Colorado Legal Services, https://perma.cc/NP97-7ZJR, and Divorce Pro, https://perma.cc/3EN3-3M45.

42. Courtroom5, https://perma.cc/36LN-VF9V (quoting Galea, “AI Might Soon Help People Who Represent Themselves in Court, Despite Ethical Concerns,” Globe and Mail (Aug. 7, 2023), https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-ai-could-help-people-represent-themselves-in-court-experts-warn-of).

43. Id.

44. Id.

45. Westlaw, LexisNexis, and other legal technological companies have rolled out generative AI products that were trained with data sets consisting only of legal authorities. These products are coupled with computerized legal research capabilities and, according to their developers, can provide accurate responses to users’ natural language queries regarding legal matters. But according to researchers at Stanford, even those generative AI tools have not completely eliminated the inclusion of hallucinated legal citations in outputs. Magesh et al., Hallucination-Free? Assessing the Reliability of Leading AI Legal Research Tools 23, https://dho.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/Legal_RAG_Hallucinations.pdf (preprint under review).

46. “DoNotPay.com CEO Browder on World’s First Robot Lawyer,” Bloomberg Tech. (Aug. 4, 2021), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/videos/2021-08-04/donotpay-com-ceo-browder-on-world-s-first-robot-lawyer-video.

47. See Morgan v. Cmty. Against Violence, No. 23-CV-353, 2023 WL 6976510, at *1, 8 (D.N.M. Oct. 23, 2023) (admonishing pro se litigant after her citation to “several fake or nonexistent opinions,” and warning that if she submitted any future filings with fake cases, the court could issue sanctions, including striking the litigant’s pleading, imposing filing restrictions, or dismissing the case).

48. Eliot, “ChatGPT and Other AI Programs Aid and Muddle Access to Justice as Non-Lawyers Seek Their Advice,” Jurist News (Mar. 7, 2023), https://perma.cc/69HN-E7E3.

49. Weiser, supra note 36.

50. Avianca, 678 F.Supp.3d at 449, 453–54 (discussing hallucinated case citations, including one that referenced internal citations to and quotations from nonexistent decisions). See, e.g., Park v. Kim, 91 F.4th 610, 612, 613–15 (2d Cir. 2024) (observing that counsel cited to a nonexistent case after relying on ChatGPT to draft a reply brief; noting that her conduct ran afoul of Fed. R. Civ. P. 11; and referring counsel to the court’s grievance panel); Iovino v. Michael Stapleton Assoc., No. 21-cv-00064, 2024 WL 3520170, at *7 (W.D.Va. July 24, 2024) (ordering lawyers who filed a brief containing fictitious citations allegedly found using ChatGPT, and who “puzzlingly [have] not replied to explain where [their] seemingly manufactured citations and quotations came from and who is primarily to blame for this gross error,” to show cause why they should not be sanctioned); Thomas v. Pangburn, No. CV423-046, 2023 WL 9425765, at *4–5 (S.D.Ga. Oct. 6, 2023) (identifying 10 cases cited in plaintiff’s briefing that “appeared legitimate, conforming to citation conventions,” but “that simply did not exist” and recognizing that “‘[m]any harms flow from the submission of fake opinions’” (quoting Avianca, 678 F.Supp.3d at 448)); Pegnatori v. Pure Sports Tech. LLC, No. 23-CV-01424, 2023 WL 6626159, at *5 n.5 (D.S.C. Oct. 11, 2023) (noting, in response to a party’s use of ChatGPT to define the term “foam” as used in a patent, that, “thus far ChatGPT’s batting average in legal briefs leaves something to be desired”); Morgan, 2023 WL 6976510, at *8 (observing, in response to a self-represented plaintiff’s citation to “several fake or nonexistent opinions,” the “many harms [that] flow from such deception—including wasting the opposing party’s time and money, the Court’s time and resources, and reputational harms to the legal system (to name a few)” and warning that future similar conduct could result in dismissal of the plaintiff’s complaint); Mescall v. Renaissance at Antiquity, No. 23-CV-00332, 2023 WL 7490841, at *1 n.1 (W.D.N.C. Nov. 13, 2023) (commenting that “the use of artificial intelligence to write pleadings . . . creates challenges, raises ethical issues, and may result in sanctions or penalties when used inappropriately”); United States v. Cohen, No. 22-2057, 2024 WL 1193604, at *2, 6, __ F.Supp.3d __ (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 20, 2024) (deciding not to impose sanctions against a lawyer who cited to nonexistent cases he found using a generative text service like ChatGPT because, while the lawyer’s conduct was “embarrassing and certainly negligent, perhaps even grossly negligent,” it was not done in bad faith); Ex parte Lee, 673 S.W.3d 755, 756–57 n.2 (Tex.Crim.App. 2023) (declining to review the arguments made in the defendant-appellant’s brief where it cited to only five cases, none of which “actually exist” in the reporter referenced, nor support the propositions asserted, and observing that “it appears that at least the ‘Argument’ portion of the brief may have been prepared by artificial intelligence”); In re Will of Samuel, 206 N.Y.S.3d 888, 891–92 (Surr.Ct. 2024) (noting, in response to petitioner’s brief containing five “fictional and/or erroneous citations as a result of his reliance” on AI, that although the court was “dubious about using AI to prepare legal documents, it is not necessarily the use of AI in and of itself that causes such offense and concern, but rather the attorney’s failure to review the sources produced by AI without proper examination and scrutiny”); M.B. v. N.Y.C. Dep’t of Educ., No. 22-CV-06405, 2024 WL 1435330, at *4 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 24, 2024) (disregarding plaintiff’s inclusion of a 14-page conversation with ChatGPT as support for the plaintiff’s argument because ChatGPT was a “chatbot notorious for inventing false information”); Kruse v. Karlen, No. ED 111172, 2024 WL 559497, at *3–5 (Mo.Ct.App. 2024) (determining, as a matter of first impression, that defendant’s conduct in filing a brief containing fictitious case citations generated by AI rose to the level of an abuse of the judicial system).

51. See People v. Crabill, No. 23PDJO67, 2023 WL 8111898, at *1 (Colo. O.P.D.J. Nov. 22, 2023) (discipline and suspension of attorney who relied on ChatGPT to draft a motion, and failed, after discovering that the cases cited were either incorrect or fictitious, to alert the court or withdraw the motion, and then blamed the citations on an intern).

52. In light of this concern, some courts require lawyers to certify whether they used AI in drafting their filings. See Berkenkotter and Lipinsky de Orlov, supra note 20 at 23 & n.8.

53. One commentator wrote, “Whether or not . . . disclosure [of privileged or confidential work product] to an LLM vendor waives attorney-client or work product privileges is unclear.” Moriarty, supra note 29 at 37. We offer no opinion on this—or any other issue—discussed in this article.

54. Florida Bar v. TIKD Services LLC, 326 So.3d 1073, 1076 (Fla. 2021).

55. Id. at 1082.

56. Allyn, “A Robot Was Scheduled to Argue in Court, Then Came the Jail Threats,” NPR (Jan. 25, 2023), https://perma.cc/NZ5K-TCA8.

57. Id.

58. Id.

59. Id.

60. Id.

61. Kahana, supra note 40.

62. Discover AI-Powered Renter Risk Ratings and Verified Tenant Reviews, Augrented, https://augrented.com.

63. See generally Utah Office of Legal Services Innovation, https://utahinnovationoffice.org.

64. See id.

65. At the same time, the Colorado Supreme Court requested that the Standing Committee on the Colorado Rules of Professional Conduct (RPC) form a subcommittee focused on possible amendments to the RPC that would address lawyer use and misuse of AI. The Standing Committee, however, does not have jurisdiction over the UPL Rules.