Municipal Partnerships for Instream Flow on Colorado’s Front Range

January/February 2026

Download This Article (.pdf)

Incorporating instream flow uses into municipal water supply planning efforts can provide numerous public benefits. This article discusses the framework and opportunity for collaborative instream flow protection in municipal water supply operations.

Colorado’s instream flow program is a dynamic approach to protecting the natural environment that encourages practical and creative solutions to evolving environmental concerns. While water rights typically involve diverting water from the stream, the instream flow program protects water in the stream. Environmental values associated with instream flow uses can work synergistically with municipal water supply operations to realize several public benefits, such as improved water quality, riparian health, urban cooling, resiliency, recreational opportunities, and aesthetic value. As illustrated by the examples discussed later in this article, the instream flow program can facilitate cooperative agreements with municipal water providers for shared beneficial use of our state’s most precious resource.

Water Rights and the Prior Appropriation Doctrine in Colorado

The prior appropriation doctrine governs the ownership and use of water and water rights in Colorado. In simple terms, the prior appropriation system is described as “first in time, first in right.” A water user that has demonstrated an intent to put water to beneficial use first has a vested and prior right to use water in that amount against subsequent water users. This system developed out of necessity during the colonial expansion westward and was influenced by Spanish settlers and early miners to allocate water in the arid environment of Colorado, as an alternative to the more common riparian system of water rights based on land ownership abutting water ways.1

The prior appropriation doctrine has been enshrined in the Colorado Constitution. Article XVI, § 5 dedicates water in Colorado as public property for use by the people, subject to appropriation, and § 6 gives the right to appropriate water for beneficial use in priority.2 The 1969 Water Rights Determination and Administration Act (1969 Act) provides the legal framework for surface and tributary ground water distribution and use under the prior appropriation doctrine.3

An appropriation of a water right under the 1969 Act, as originally codified, meant “the diversion of a certain portion of the waters of the state and the application of the same to a beneficial use.”4 Similarly, beneficial uses were limited to diversions of water from the stream system for extractive uses such as domestic or municipal, irrigation, and manufacturing or industrial activities.5 Environmental uses of water, including instream flows, were not initially addressed in the 1969 Act but were later incorporated through amendments.6

Colorado Instream Flow Program

The Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB) was first established by the Colorado legislature in 1937 to protect and develop Colorado’s water resources for the benefit of present and future generations.7 It was not until the national environmental movement in the late 1960s, however, that discussions regarding the value of instream flows and role of the CWCB in the protection of such flows began to garner serious attention and focus.8 In 1973, those discussions culminated in the passage of SB 97 to create the Colorado Instream Flow and Natural Lake Level Program.9 SB 97 was unprecedented at the time and amended the 1969 Act to define beneficial use of a water right to include use by the CWCB for protection of stream flows within a specified reach without a diversion of water from the stream.10

Under the instream flow program, the CWCB has exclusive authority to hold a water right for instream flow uses in Colorado and may appropriate water rights or acquire existing water rights for instream flow, provided that it determines that such water rights are necessary to preserve or improve the natural environment to a reasonable degree.11 Since the program’s inception, the CWCB has appropriated nearly 1,700 instream flow rights across 9,700 miles of stream and completed over 35 water acquisition transactions.12

The General Assembly has reinforced and expanded the CWCB’s ability to acquire water rights for instream flow purposes on several occasions.13 Acquiring and changing senior water rights for instream flows in over-appropriated systems can add great value by preserving the priority date, and therefore the availability, of the water for greater instream flow protection.14 Acquisitions can be donated to or purchased by the CWCB, and the statutory language specifically anticipates potential acquisitions from governmental entities, like municipalities.15 Other free-market developments to the Colorado instream flow program enacted by the state legislature over the years include streamlined processes for loans of water rights for instream flow use, instream flow protection for mitigation releases, and stream flow augmentation plans.16 These developments provide additional opportunities for water users, including municipalities, to participate in the program in support of instream flows.

In addition to implementing the instream flow program, the CWCB is tasked with creating the Colorado Water Plan, which addresses the state’s water challenges through collaborative water planning, including expanded opportunities for instream flow protection.17

Case Studies Along the Front Range

The instream flow program provides reasonable protection of the environment for benefit of the public and is emphasized in the Colorado Water Plan as a balanced approach to addressing environmental needs in the face of climate change.18 Similarly, municipal water service providers, acting in the interest of their respective jurisdictions, must often balance water supply with other public interests. Municipal water projects and water supply planning efforts can be designed to address multiple needs and related uncertainties across a jurisdiction, informed by integrated planning efforts. The various public interests typically considered by municipalities may align with instream flow protection in many respects. The Colorado Water Plan includes several policy considerations that highlight this potential overlap between municipal water interests and instream flows.19

Fundamentally, the Colorado Water Plan encourages a holistic, collaborative approach to water management that balances multiple uses and benefits to meet water shortages throughout the state.20 As competition for water resources in Colorado becomes more pronounced with increased demands and costs, the benefits of water sharing and collaboration will also likely increase.21 The Colorado Water Plan focuses on thriving watersheds as an action area to support stream health, recreational uses, resiliency, erosion control, and water quality, all of which provide tangible benefits to municipal water service providers.22 Accordingly, more water in the stream system for instream flows can be a natural complement to a municipality seeking to balance growing water demands with related public interests. The following examples demonstrate how instream flow uses can benefit municipal water supply, and vice versa, to realize this balance in a meaningful way.

Boulder Creek Instream Flow Project

The Boulder Creek instream flow project is a long-standing cooperative project that has been operating in Boulder County for almost 35 years. This project has operated successfully due in large part to the partnership between the City of Boulder and the CWCB and their collaboration with neighboring water users in Boulder County to support environmental stream flows and other uses in the creek.

In the early 1990s, Boulder donated a suite of valuable senior water rights to the CWCB to establish a year-round instream flow program on North Boulder and Boulder Creeks.23 The acquisition was memorialized in a series of donation agreements between Boulder and the CWCB pursuant to CRS § 37-92-102(3), following certain legislative amendments throughout the 1980s that clarified and enhanced the CWCB’s acquisition authority for instream flows.24 Boulder and the CWCB, as co-applicants, also received a water court decree to change the use of the donated rights to include instream flow uses for the project.25

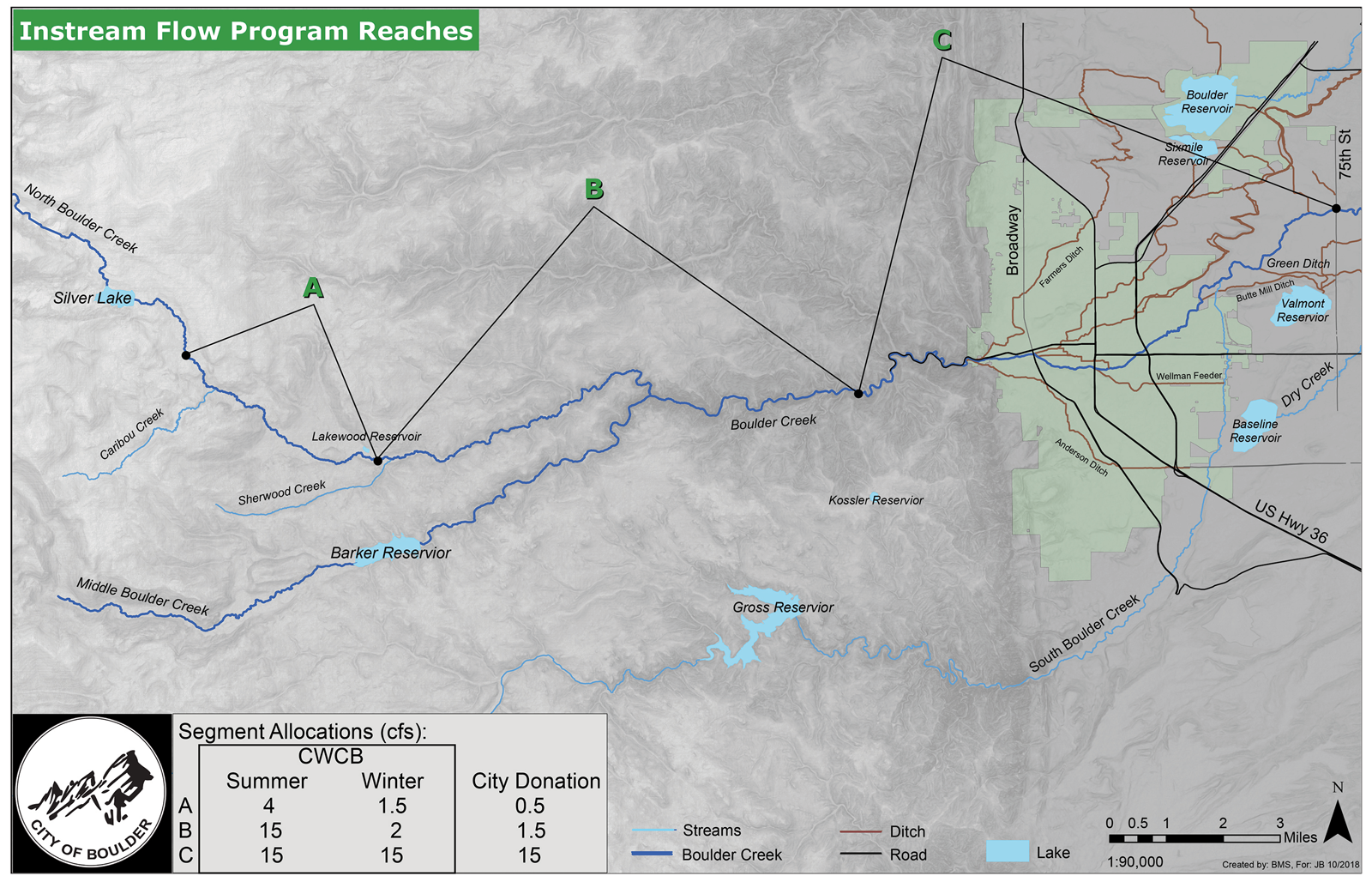

The Boulder Creek instream flow project protects three segments from below the Silver Lake Reservoir near the headwaters of North Boulder Creek down to 75th Street in Boulder County (see fig. 1). The donated rights include reservoir releases, bypassed diversions, and changed irrigation ditch shares to support instream flows throughout the year. As part of its donation to the CWCB, Boulder retained the right to use water available under the donated rights (1) for municipal purposes under certain conditions, including drought and emergency conditions in its municipal water supply operations; (2) for municipal purposes anytime they are not needed to meet instream flow amounts; and (3) for beneficial reuse downstream of the protected reaches.26 This provides operational flexibility for the city’s municipal water supply while also supporting instream flow uses by the CWCB in most years. Its participation in the Boulder Creek instream flow program has also helped the city address US Forest Service regulatory requirements for bypasses related to its diversions from North Boulder Creek as part of federal permitting for one of its raw water pipelines.27

The City of Boulder has a long-standing environmental ethos that incorporates instream flows into its water supply planning and operations. Boulder’s water supply planning documents from the 1980s identified the goal of supporting instream flows in Boulder Creek to enhance aquatic and riparian ecosystems, reflecting city planners’ prediction that dry-up periods in the creek would become more severe and frequent with increased water demands.28 Subsequent Boulder water supply and land use planning documents have included similar goals focused on balancing instream flows and environmental preservation with municipal water demands and operations, and emphasizing the connection between stream health and reliable drinking water supplies.29

Because the protected stream segments run through the Boulder city limits, and extend both above and below the city, the project benefits water quality, riparian health, and resiliency in the Boulder municipal watershed and water system operations and provides additional environmental benefits to the larger Boulder County community.

Gross Reservoir Environmental Pool Project

The cities of Boulder and Lafayette entered into an intergovernmental agreement in 2010 with Denver Water to establish a 5,000 acre-foot environmental pool in an enlarged Gross Reservoir to augment stream flows in South Boulder Creek.30 Boulder recognized the need to address low flows on South Boulder Creek as a key goal in its planning documents and identified Denver Water’s planned expansion of Gross Reservoir as an opportunity to use upstream storage to establish a robust instream flow program. Lafayette similarly identified Gross Reservoir for potential water storage in its water rights decrees, providing both a water supply and environmental benefit to its operations. The parties proactively agreed to cooperate to mitigate the reservoir expansion’s impacts to aquatic resources in the South Boulder Creek basin by creating and operating the environmental pool.31

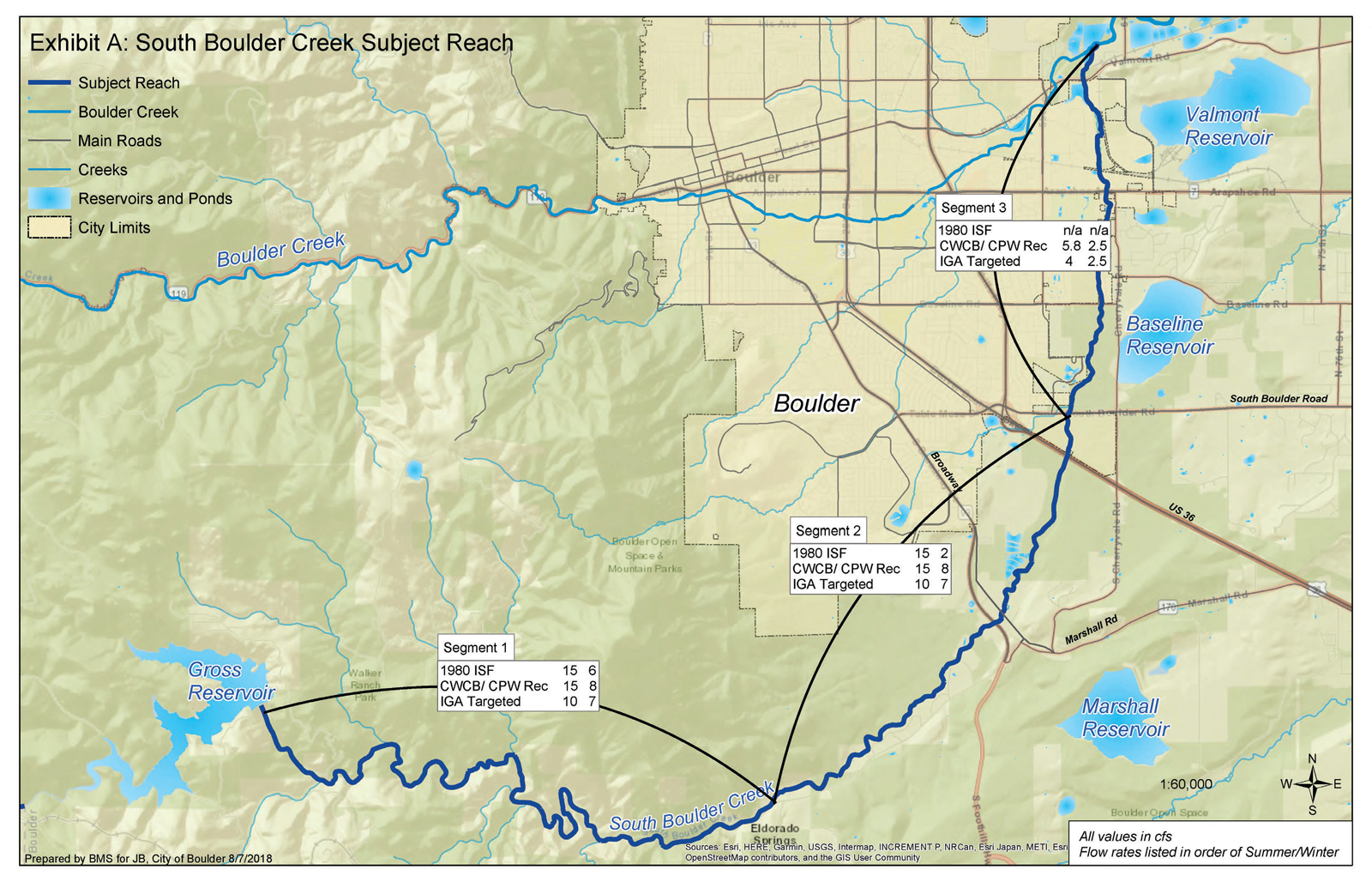

Coordinated with municipal water system operations, releases from the environmental pool will allow Boulder and Lafayette to store their decreed water rights for later release to meet specific target flows below Gross Reservoir in South Boulder Creek throughout the year. The segments identified for the target flows include Gross Reservoir to South Boulder Road (Upper Segment, depicted as segments 1 and 2 in fig. 2) and South Boulder Road to the confluence with Boulder Creek (Lower Segment, depicted as segment 3 in fig. 2).32 The agreement also includes provisions to address emergencies such as extended drought or an unexpected problem with water storage, conveyance, or treatment infrastructure to allow for flexibility in operations to meet both target flows and municipal needs.

Boulder’s releases from the environmental pool are protected as instream flows according to a Water Delivery Agreement with the CWCB dated September 9, 2019, and a water court decree entered for Boulder, Lafayette, and the CWCB.33 Water released by Boulder to meet the target flows will be protected for instream flow uses to the extent that such flows do not exceed the amounts that CWCB has determined to be appropriate to preserve the natural environment to a reasonable degree in South Boulder Creek. Boulder’s target flow releases will support CWCB’s existing appropriated instream flow rights up to the specified amounts (see fig. 2). Boulder may then redivert the water downstream of the protected reaches for its municipal uses.

The environmental pool will provide permanent, dedicated storage for water rights owned by Boulder and Lafayette to be released to enhance stream flows in South Boulder Creek prior to downstream uses for municipal purposes by the parties. These operations provide added flexibility, resiliency, and redundancy to the cities’ respective water supply systems. In turn, the enhanced stream flows will benefit 17.3 miles of South Boulder Creek, including Eldorado Canyon State Park, South Boulder Creek Natural Area, and City of Boulder open space lands, and will support native fish populations and riparian and wetland habitats.

Poudre Flows Project

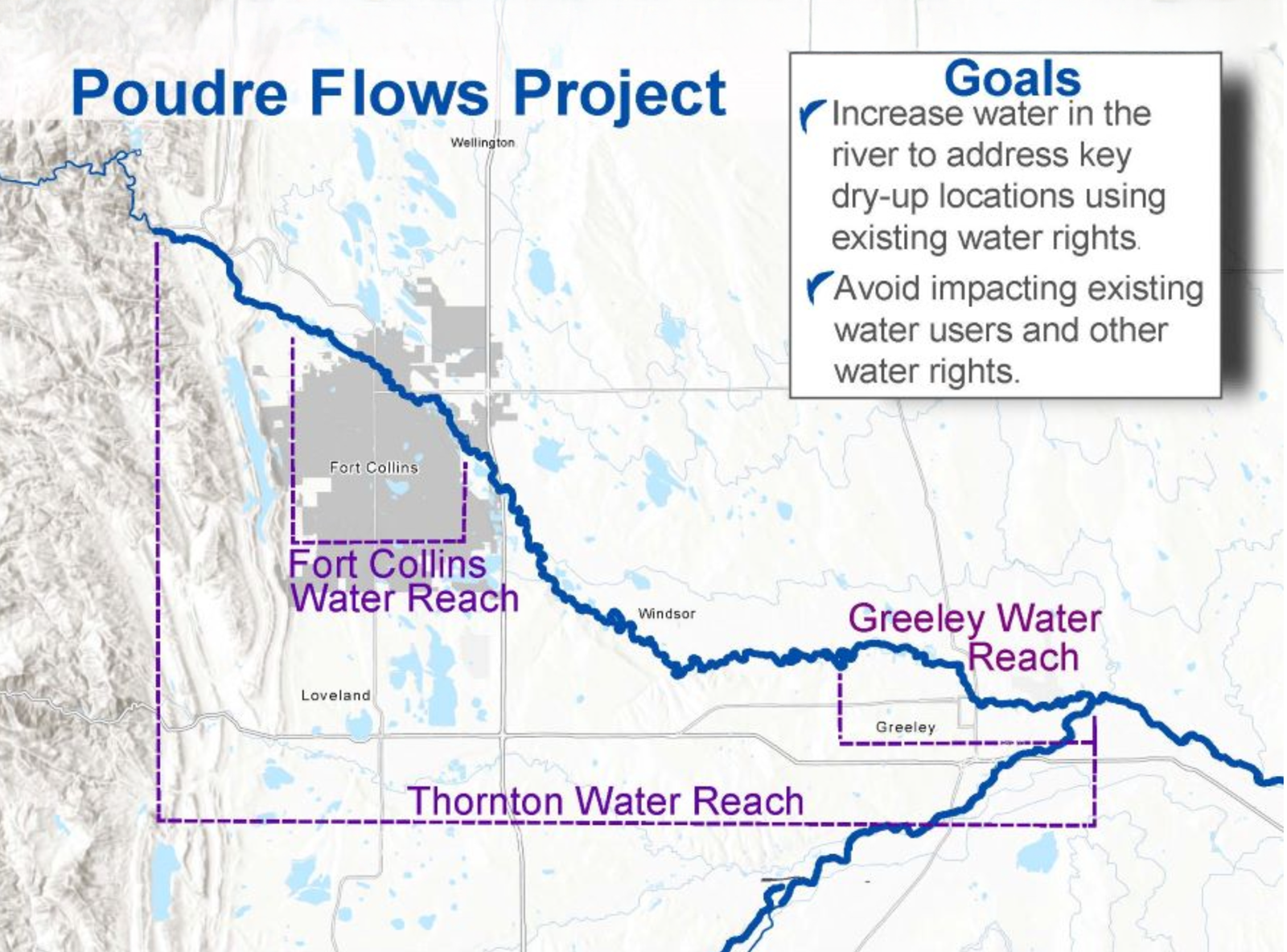

The Poudre Flows Project is the first stream flow augmentation plan developed pursuant to CRS § 37-92-102(4.5).34 It is a partnership amongst the CWCB; municipalities of Fort Collins, Thornton, and Greeley; Colorado Water Trust; Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District; Cache la Poudre Water Users Association; and Colorado Parks and Wildlife. The project will augment stream flows through a 52-mile reach of the Cache la Poudre River, with an overarching goal to improve river health (see fig. 3).35 The concept was first envisioned as part of the Poudre Runs Through It working group, a collaborative group of diverse partners and stakeholders in the Poudre River.36 The City of Fort Collins planning priorities incorporate similar goals, including to “[p]rotect community water systems in an integrated way to ensure resilient water resources and healthy watersheds.”37

The project anticipates that the CWCB, through agreements with water right owners, including Fort Collins and Greeley, will use previously changed and quantified water rights owned by these municipalities and potentially others to augment stream flows in six segments of the Poudre River spanning from Canyon Gage to the confluence with the South Platte River.38 Besides the instream flow protection of the environment to a reasonable degree, project partners have identified numerous additional benefits such as connectivity for fish passage and decreased temperatures and nutrient concentrations, all while avoiding impacts to existing water rights and operations.39

Conclusion

By integrating water supply planning with a holistic approach to water development and management that provides multiple public benefits, municipalities can become strong partners with the CWCB. Together, they can help protect instream flows and balance growing water demands and future uncertainties with the environmental values that make Colorado a beautiful place to live.

Related Topics

Notes

citation Pault-Atiase, “Municipal Partnerships for Instream Flow on Colorado’s Front Range,” 55 Colo. Law. 48 (Jan./Feb. 2026), https://cl.cobar.org/features/municipal-partnerships-for-instream-flow-on-colorados-front-range.

1. See generally Coffin v. Left Hand Ditch Co., 6 Colo. 443, 447 (Colo. 1882).

2. Colo. Const. Art. XVI, §§ 5–6. See also Colo. River Water Conservation Dist. v. CWCB, 594 P.2d 570, 573 (Colo. 1979) (“The reason and thrust for this provision was to negate any thought that Colorado would follow the riparian doctrine in the acquisition and use of water.”).

3. CRS §§ 37-92-101 et seq.

4. CRS § 148-21-3 (1969) (emphasis added). See also Colo. River Water Conservation Dist., 594 P.2d at 574.

5. Id.

6. See Bassi et al., “ISF Law—Stories About the Origin and Evolution of Colorado’s Instream Flow Law in This Prior Appropriation State,” 22(2) U. Denv. Water L. Rev. 395 (2019), https://dnrweblink.state.co.us/cwcbsearch/ElectronicFile.aspx?docid=211090&dbid=0.

7. See Colorado Department of Natural Resources, Colorado Water Conservation Board, https://cwcb.colorado.gov/about-us.

8. Bassi, supra note 6 at 396–97.

9. SB 97, 49th Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Colo. 1973). See CRS § 37-92-102(3).

10. Bassi, supra note 6 at 398. See also Colo. River Water Conservation Dist., 594 P.2d at 576. SB 97 was carefully drafted to provide environmental protection through the CWCB, as a fiduciary to the public, without inviting riparian rights for adjacent landowners. Id. The Colorado Supreme Court reiterated this important distinction in St. Jude Co. v. Roaring Fork Club, LLC, 351 P. 3d 442 (Colo. 2015), ruling that a diversion from a steam for private instream flows is a “forbidden right” contrary to the prior appropriation doctrine; only the CWCB, with strict limitations identified by the general assembly, can hold an instream flow right for the benefit of the public. Id. at 451.

11. CRS § 37-92-102(3) (The CWCB is “vested with exclusive authority, on behalf of the people of the state of Colorado, to appropriate . . . such waters of natural streams . . . as the board determines may be required for minimum streamflows . . . to preserve the natural environment to a reasonable degree.” The board also may acquire water rights “in such amount as the board determines is appropriate for streamflows . . . to preserve or improve the natural environment to a reasonable degree.”). Legislation enacted in 2002 expanded the Colorado instream flow program to provide that water rights may also be used by the CWCB to improve the natural environment (and not just for preservation purposes). Bassi, supra note 6 at 391.

12. Colorado Department of Natural Resources, Colorado Water Conservation Board, “Instream Flow Program,” https://cwcb.colorado.gov/focus-areas/ecosystem-health/instream-flow-program.

13. See Bassi, supra note 6 at 405–06, 417–18.

14. Id. at 406. The Colorado Water Trust was formed in 2001 to support Colorado’s instream flow program by promoting voluntary, market-based efforts to restore stream flows in Colorado’s rivers. The Water Trust has been instrumental in facilitating and streamlining the acquisition of water rights from willing partners for use by the CWCB. See https://coloradowatertrust.org.

15. CRS § 37-92-102(3).

16. See generally CRS §§ 37-83-105, 37-92-102(8), 37-92-102(4.5).

17. The Colorado Water Plan was adopted by the CWCB in 2023 as a framework for decision-making to address water challenges and build resiliency in the state. The 2023 Water Plan is an update to the first iteration of the plan released in 2015. See https://cwcb.colorado.gov/colorado-water-plan.

18. See St. Jude Co., 351 P. 3d at 449 (in its use of water for instream flows, the CWCB has a “‘statutory fiduciary duty’ to the people . . . to both protect the environment and appropriate only the minimum amount of water necessary to do so . . . .”).

19. Colorado Department of Natural Resources, Colorado Water Conservation Board, Colorado Water Plan (2023), https://dnrweblink.state.co.us/CWCB/0/edoc/219188/Colorado_WaterPlan_2023_Digital.pdf.

20. See id. at 217–19, 231, 233 (“All areas of the Water Plan are interconnected, and projects need to consider multi-purpose, multi-benefit solutions.”).

21. See id. at 217 (“Multi-purpose projects better address water supply challenges across municipal, agricultural, environmental, and recreation sectors as they occur.”).

22. See id. at 181, 204–07 (stream health and related environmental benefits can enhance municipal supply or improve the quality of life in urban areas).

23. See Decree, In re Application for Water Rts. of the Colo. Water Conservation Bd. on Behalf of the State of Colo. and Water Rts. of the City of Boulder, No. 90CW193 (Colo. Water Div. 1, Dec. 20, 1993).

24. Id. See Bassi, supra note 6 at 405–07.

25. Decree, supra note 23.

26. See id.

27. Bassi, supra note 6 at 408–09.

28. City of Boulder Source Water Master Plan: Vol. 2—Detailed Plan 2-1, 2-3, 3-77, 5-20 (Apr. 2009) (discussing previous planning efforts and priorities regarding instream flows), https://bouldercolorado.gov/media/7670/download?inline.

29. Id. at 3.71, 5-21 to 5-33, 7-3. See also Boulder Valley Comprehensive Plan: 2020 Mid-Term Update 31, 62 (adopted 2021), https://bouldercolorado.gov/media/3350/download?inline.

30. See Decree, In re Application for Water Rts. of City of Lafayette, City of Boulder, and Colo. Water Conservation Bd. in Boulder Cnty., No. 17CW3212 (Colo. Water Div. 1, Feb. 11, 2021). The author represented the City of Boulder in Case No. 17CW3212 and was involved in prosecuting the case and negotiating the underlying agreement with CWCB.

31. Denver Water’s enlargement of Gross Reservoir is the subject of pending litigation.

32. The target flows and target reaches are based on previously collected data and analysis by Colorado Parks and Wildlife using the R2Cross method, which supported CWCB’s previous instream flow appropriations.

33. See id. CRS §§ 37-92-102(3), 37-87-102(4).

34. The cities of Fort Collins and Greeley were instrumental in getting HB 20-1037 passed to authorize the CWBC to use water rights previously decreed for augmentation uses for instream flows. Castle, “To Boost Poudre River Flows, Cities, Conservationists Craft New Plan From Old Playbook,” Water Education Colorado (Jul. 3, 2019), https://watereducationcolorado.org/fresh-water-news/to-boost-poudre-river-flows-cities-conservationists-craft-new-plan-from-old-playbook. See also HB 1037, 75th Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Colo. 2020), https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/hb20-1037.

35. See Boissevain, “Poudre Flows: Collaboration to Protect the Cache la Poudre River,” Colorado Water Trust (Oct. 29, 2024), https://coloradowatertrust.org/collaboration-to-protect-the-cache-la-poudre-river.

36. City of Fort Collins, “Poudre Flows,” https://www.fcgov.com/poudreflows.

37. Id.

38. See Application, In re Application for Water Rts. of Cache La Poudre Water Users Ass’n, City of Fort Collins, City of Greeley, Colo. Water Tr., N. Colo. Water Conservancy Dist., City of Thornton and Colo. Water Conservation Bd. in Larimer and Weld Cntys., No. 21CW3056 (Colo. Water Div. 1 Apr. 29, 2021).

39. See “Poudre Flows,” supra note 36.